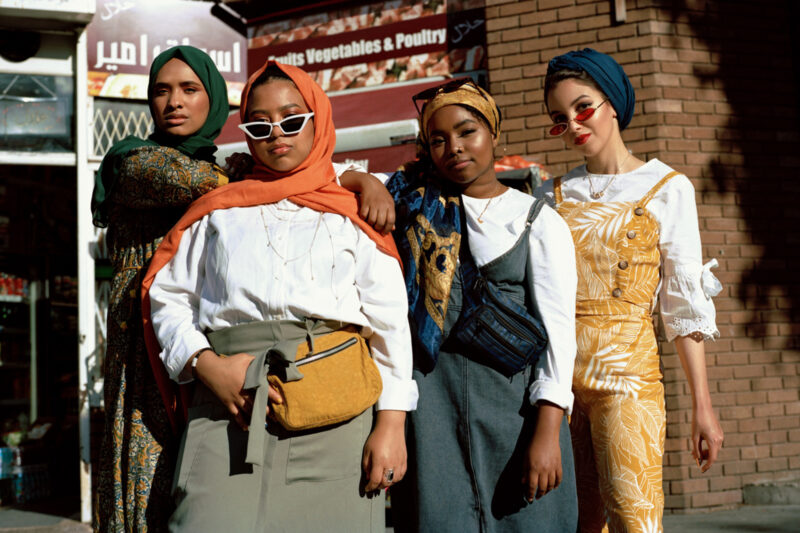

Diversity and inclusion is a fact of life for Gen Z Muslims

Hyphen’s poll suggests that UK Muslims and their fellow Britons have more in common than ever before

–

Gen Z Muslims in the UK may be the country’s most integrated Muslims ever. This appears to be the overall theme of Hyphen’s latest poll, which suggests that the social distance between young Muslims and fellow Britons has never been narrower.

The results of the survey of over 2,000 Gen Z respondents aged 16-24, carried out in conjunction with Savanta, reflects the confidence of a generation more likely to see inclusion and integration in the UK as a social fact — and almost taken for granted — than a topic of political debate.

As the poll shows, a number of key factors make Gen Z Muslims more like their fellow Britons — and different from their parents and grandparents. Nobody would be surprised to hear that new immigrants and people born in the UK have a different perspective on integration. What the Hyphen survey suggests, however, is that a Rubicon may have been crossed in the experiences of the children and grandchildren of migrants.

British Muslims who were born in the 1970s may have sometimes found the language of integration irksome and clunky: I am reminded of Norman Tebbit’s 1990 “cricket test”. Yet the conversation of that time did often reflect the realities of being a bridging generation and of having to navigate and reconcile two different worlds: domestic environments where the Muslim influence was often dominant, and school, college and work, where it was not.

For Gen Z Muslims, there may be a stronger sense of the UK’s diversity being a natural thing. The survey shows that 48% of respondents born in the UK are considerably more likely than young Muslims who were born abroad to identify equally as British and Muslim.

The poll also suggests that the effects of integration are being felt around the UK. For many people born in this century, the presence of ethnic and faith diversity in the classroom has been the norm from the start. If that has been the narrative in major cities such as London, Manchester and Liverpool, it is now increasingly a story of the UK’s suburbs and large towns.

There are, of course, still subtle differences between Gen Z Muslims and their peers on questions of faith in an increasingly secular nation. Gen Z Muslims are two or three times more likely to visit a place of worship, to pray at home regularly, or to seek spiritual advice from a faith leader. The search for spirituality has also driven many of them online, with 71% saying they at least sometimes use social media platforms to get spiritual advice. This is in stark contrast to the average age of those identifying as Christian rising to over 50 in the most recent census.

There also seems to be a wider acceptance of Islam in the UK. Although young non-Muslim Britain has never been more secular, most Gen Zs are sympathetic towards Islam as a minority faith — with more than six out of 10 in favour of granting Muslims time off to celebrate Eid.

But that does not mean anti-Muslim prejudice has disappeared. Half of Gen Z Muslims report that they have experienced some form of Islamophobia at school, college or university — and women report a higher incidence than men. Those findings should serve as a warning against complacency about the issue.

Yet, even here, there may be another formative difference in the experience of Gen Z Muslims and those who came before them. Muslims born in the 1970s experienced a seismic change in the public profile and scrutiny of Islam. London Mayor Sadiq Khan, for example, born in 1970, was a young adult when the Salman Rushdie affair first catapulted arguments about levels of Muslim integration onto the front pages.

Humza Yousaf, the new First Minister of Scotland, born in 1985, is a millennial who was 16 when the events of 9/11 occurred. He has talked about how racism and anti-Muslim prejudice were formative political experiences. Though Gen Z Muslims have inherited many of the complex legacies of the post-9/11 era, they have not experienced the same dramatic shift in how they are viewed.

On the economy, the optimism felt by some Gen Z Muslims could seem counter-intuitive for a generation facing such a precarious future. No fewer than two-thirds of Gen Z Muslims — and a similar number of their non-Muslim peers — predict that they will be homeowners by the age of 30. The average age of a homeowner was 29 a decade ago, but it has risen to 32, according to data from the UK bank Halifax. Something will have to change if this generation is to realise its ambitions and buck a trend that has been going in the opposite direction.

This coronation year marks three-quarters of a century since the advent of a modern, multi-ethnic and multi-faith United Kingdom. The docking of the Windrush at Tilbury, Essex, in June 1948, 75 years ago, has become a symbolic starting point not only of Black British experience but also of the story of Commonwealth migration and integration. As Hyphen’s poll demonstrates, the attitudes of British Muslims reflects the confidence of an increasingly diverse nation. But more may need to be done for that optimism to be sustained as young people seek to mark their influence on every sphere of our economy, society and civic life.

• Read more on Hyphen’s exclusive Gen Z poll

Newsletter

Newsletter