Food of love

Cooking and sharing meals is one of the best ways to show people we care — and it’s backed up by research

The connection between food and love has existed for centuries. One of the earliest examples can be found in the biblical Song of Songs: “Eat, friends, and drink; drink your fill of love.” My favourite modern-day version of this idea comes in a line from The Cure’s 1992 song Friday I’m In Love: “It’s such a gorgeous sight to see you eat in the middle of the night” — words that will evoke familiar feelings in anyone who has ever experienced the joy of scoffing a 2am burger with their partner.

Like most other good things in life, it has also long been exploited by commerce. Who can forget the 1980s TV adverts in which a man jumps out of a helicopter, swims with sharks and skis through forests at breakneck speed to bring a box of chocolates to a woman, “all because the lady loves Milk Tray”.

Then there’s the archetypal restaurant dinner date, during which couples make an elaborate ritual out of the simple act of eating, lingering over their meals and gazing into one another’s eyes. While there are reports that the dinner date’s popularity is waning, no romcom is complete without such a scene and reality TV series based around the practice remain hugely popular.

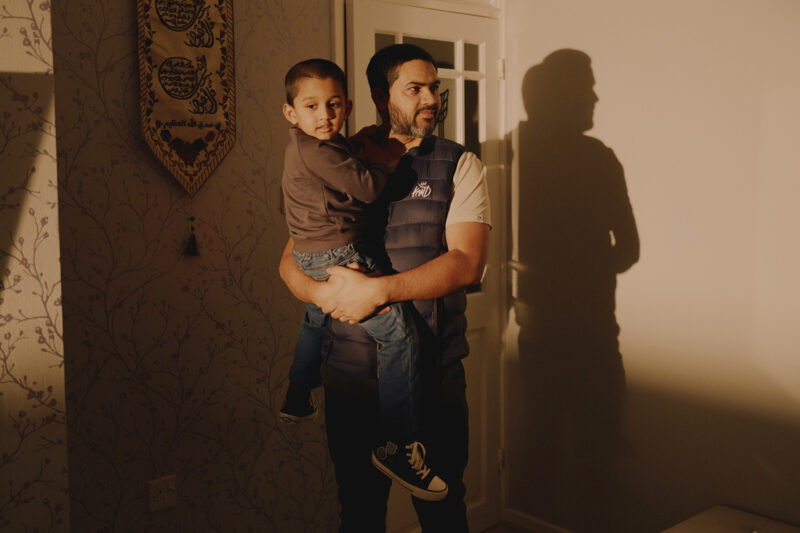

The intimacy of sharing food also extends beyond romantic love and reaches into family life. The most vivid memories of this, for me, are the times when my parents took me and my sisters with them to dinner on Valentine’s Day. Every Asian restaurant in Bradford was full of families marking the occasion: kids, parents and grandparents all together. I suspect that this was, at least in part, because of the cultural or generational practice of not leaving children at home with a babysitter. But it was also because the idea of having a special meal and not sharing it with your kids was incomprehensible.

Remembering people’s favourite dishes and taste preferences is how we convey that we care

A few years ago, a US poll conducted by NPR, the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation and the Harvard School of Public Health found that “food is considered an important way to show affection” in more than a quarter of families. I suspect that figure would have been much higher in certain cultures or other parts of the world.

It’s easy to see why so many people everywhere feel this way. In the preparation of food, we see care, nourishment and attentiveness in action. In many families, love is shown in deeds, not words. Instead of declaring depth of sentiment verbally, a favourite meal is cooked for a child returning home or a visiting relative. Recently, the idea of carefully prepared fresh fruit as a love language for South Asian families became such a popular topic that it gave birth to a whole subgenre of food writing.

Remembering people’s favourite dishes and taste preferences is how we convey that we care. My grandfather used to always buy ilish — my mum’s favourite fish — when she visited. When my niece and nephew come to see me, I always make shepherd’s pie with spicy lamb keema and a sweet potato mash because they once happened to mention that they liked it. For me, there is something both primal and spiritual in this instinct. Maybe it stems from breastfeeding, an act of motherly sacrifice in which service, nourishment and affection are all bound together.

One of the most powerful examples of the bond between food and love can be seen in the Qur’an, which instructs: “So eat of the lawful and good food which Allah has provided for you, and be grateful for the favour of Allah.” (Surah An-Nahl: 114).

Foods such as olives, pomegranates, grapes, figs, honey and milk are all described in the Qu’ran and often presented as examples of God’s benevolence and care in times of distress or suffering. Surah Taha: 80 reminds us that “we sent down to you Al-Manna and quails” when Musa and the Israelites were wandering lost in the wilderness for 40 years. When Maryam, mother of the prophet Isa, was despairing and labouring alone in the desert, Allah reassures her: “Do not grieve! Your Lord has placed a small stream at your feet. Shake the trunk of the palm towards you and fresh, ripe dates will drop down onto you. Eat and drink and delight your eyes.” (Surah Maryam: 23-26).

The idea that God did not forsake Maryam when she was at her most vulnerable, and instead provided food and water, is of great comfort to me and to generations of Muslim women before me. My mother packed dates for me to take to the hospital when I gave birth, in accordance with the widely held belief among Muslims, recently backed up by modern medical research, that the fruit is helpful during and after labour.

Another study by researchers at Columbia University shows that the act of food sharing and feeding is a significant indicator of the level of intimacy within romantic relationships. There is a flipside to this, though. In my experience, sharing food badly can have the opposite effect — and not just in romantic scenarios. After all, we all have friends who we would be perfectly happy to go for tapas or a small plates sharing meal with and those with whom we would never consider it.

With that in mind, sometimes it’s preferable to just show yourself a bit of love. One of the most powerful instances of this that I ever witnessed was when I was studying in the US. The day after Valentine’s Day, a young woman walked into one of the university common rooms holding an elaborately wrapped box that she had just bought in the post-holiday sale. I remember watching in awe as she nonchalantly opened it and devoured one chocolate-covered strawberry after another, while reading a book. She seemed so liberated, eating alone, indulging in public and flouting social convention that the scene has stuck with me to this day.

In all the ways we experience food — whether alone, with a partner, a group of friends or the whole family — amid the myriad tastes and textures, it is the comfort, the care, the familiarity and the love that keeps our hearts, as well as our stomachs, full.

Newsletter

Newsletter