The unsettling, dreamlike world of author Jamil Jan Kochai

The Afghan-American author’s latest collection of short stories has attracted both controversy and acclaim. Now it is shortlisted for a coveted US National Book Award

–

Like many boys at his California high school, Jamil Jan Kochai spent a large portion of his teenage years playing the video game Call of Duty, a first-person shooter set partly in Afghanistan during the Soviet invasion of the 1980s. However, he found taking control of a US marine and blasting through a landscape close to his heart a disturbing experience.

Kochai’s family is originally from Logar province, just over 50 miles south of Kabul. “I can still see that image of the wave of Afghan fighters, all wearing traditional Afghan clothes, and you’re just mowing them down,” he said, speaking via Zoom from his home in Sacramento, California.

The urge to humanise characters depicted in video games, movies and the western media as either threats or collateral damage in a far-off conflict spurred Kochai, now 30, to become a writer. His debut novel, 99 Nights in Logar, published in 2019, told the story of an Afghan boy named Marwand who returns from the US to his home country, then teams up with his cousins on an adventure in search of a missing dog. By turns playful and moving, the book includes a multiplicity of Afghan characters, from Taliban fighters to a young couple in love.

Kochai’s new collection, The Haunting of Hajji Hotak and Other Stories, references his teenage obsession with gaming more directly. In the opening story a boy playing a first-person shooter imagines seeing “uncles and aunts and cousins” in the pixelated Afghan landscape. Breaking the game’s violent logic, rather than going into battle he tries to rescue them from the Soviet forces. Kochai’s motivation, he told me, was to turn these “non-playable characters into actual human beings”.

Kochai’s perspective-bending work has attracted widespread critical acclaim. He won a scholarship at the prestigious Iowa Writers’ Workshop, which he attended between 2017 and 2019, and in 2020 was shortlisted for a Pen/Hemingway Award for 99 Nights in Logar. The day before we spoke, The Haunting of Hajji Hotak was shortlisted for a US National Book Award, the winner of which will be announced later in November.

A genial, bearded figure, Kochai explains that his work is grounded in his family’s experience of the Soviet occupation of Afghanistan, which lasted from 1979 to 1989. He was born in a refugee camp in Peshawar, northern Pakistan, in 1992. One year later, he arrived in California with his mother. His father, who had already moved to America, still cannot read English. He taught his son Pashto poetry and took his children on regular trips back to Logar to keep their connection to what he still viewed as his true home. Speaking only Pashto and Farsi, Kochai learnt English at elementary school.

Logar remains Kochai’s spiritual home, too. His first novel memorialises the province’s compounds and orchards, checkpoints and open sewers; its days, measured by prayer times; and its people, scarred by decades of conflict.

The most famous fictional depiction of modern Afghanistan is Khaled Hosseini’s 2003 novel The Kite Runner. But Kochai considers it “a very simplified depiction” of the country. It is, he says, “very black and white — these are the bad guys; these are the good guys”.

“Much of what I accomplished early on in my career was very much an attempt to resist pretty much everything he has done. So I do owe that to him,” he told me.

Faithful, faithless or somewhere in between, Kochai’s characters have an organic rather than polemical relationship with religion. Also, he is not interested in explaining Islam to non-Muslim readers.

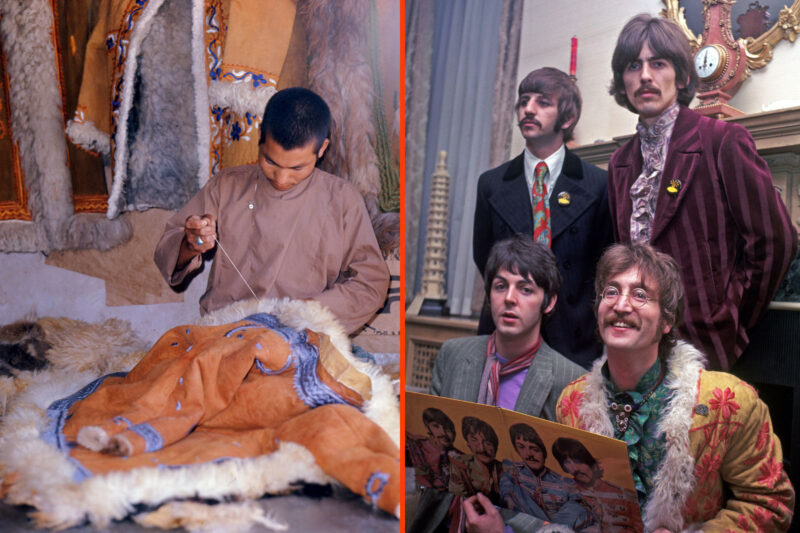

Kochai’s fiction, by contrast, is dreamlike and unsettling, filled with unresolved and unresolvable contradictions. In Return to Sender, a story from his new collection, a mother lovingly stitches together her dead child’s body, piece by piece. It is a fitting metaphor for the author’s approach to writing. “It’s fractured. It comes out in bits and pieces,” he said.

Throughout his work, Kochai tells and retells the story of the death of his father’s brother Watak during the Soviet occupation. Recently, he returned to Afghanistan and more aspects of the tragedy were revealed to him, though he doesn’t say exactly what.

“I don’t know if it’s going to take a lifetime to fully understand all the different elements of just this one story — let alone all the others that I’ve heard throughout my life,” he said.

The challenge for Kochai, as a writer, is to take such raw and painful material and pour it into the mould set by influential magazines such as The New Yorker, in which he has been published. But this mix of contrasting aesthetics — family stories, passed on by word of mouth, versus tightly workshopped prose — energises his writing. In one story from Hajji Kotak, based on an Afghan folk tale, a character turns into a monkey. In another, titled Occupational Hazards and reminiscent of George Saunders at his best, we learn of a man’s physical and emotional labours through his CV.

Kochai includes only a handful of white characters in the short story collection, so he was puzzled when a New York Times review accused him of having “a distracting fixation on whiteness” and of representing Americans as “broadly painted imperialists”. The novelist and journalist Elliot Ackerman, singled out one particular character in The Parable of the Goats: a fighter pilot named Billy Casteel, whose plane is downed by an Afghan man whose son has been killed fighting the Americans. Kochai considers it a strange example as, in an earlier draft, he had given Casteel no personality at all, but later decided to include a backstory about him growing up on a farm in order to avoid the very accusation of caricature that Ackerman ended up making.

Could Ackerman’s past as a marine who fought in Afghanistan have influenced his reading of the book? “I do wonder if that story in particular had a very profound emotional effect upon him,” said Kochai. “He was just very upset by reading the story and then decided to go at the book as a whole.”

The publicity the review generated has been useful, though. Many readers, including me, were alerted to The Haunting of Hajji Hotak and Other Stories by the resulting social media kerfuffle. On Twitter, Kochai admitted that “a certain review almost ruined my morning,” but thanked commenters — Afghans especially — who had stepped in to support him.

Kochai ends his acknowledgements in the book by writing: “Ultimately, all praise be to Allah (subḥānahu wataʿālā)”, an unusual declaration in the largely secular literary world. I asked him about his relationship with religion. The first narratives he grew up with, he explained, were passed on by his grandmother telling stories from the Qur’an and his father reciting the hadith.

For his characters, Islam is an ever-present force. When a father tells a policeman that his son is missing, he is told to ask God for help. “I don’t pray,” he answers, and the officer’s face is overcome with pity.

Faithful, faithless or somewhere in between, Kochai’s characters have an organic rather than polemical relationship with religion. Also, he is not interested in explaining Islam to non-Muslim readers. There is an amusing moment in one story when an Afghan university lecturer working in the US keeps trying to cram books onto his Introduction to Islam course, feeling “an overwhelming pressure to explicate every political, theological, philosophical, and historical nuance of a 1,400-year-old religion he was no longer sure belonged to him”.

Perhaps the most sinisterly effective moment in the collection is the final, titular story. Told in the second person, it follows an intelligence officer spying on an Afghan family. Within it lies a critique of the US surveillance state — Kochai’s own family were briefly checked up on by the FBI after 9/11 — but it is also about the discomfort of the writer’s accumulation of private intimacies in service of his work.

Often, Kochai will be listening to one of his father’s stories and then begin surreptitiously recording him. “I would just be sitting,” said Kochai, “and, all of a sudden, this trigger goes off in my head and I start taking notes on the story, sort of almost unconsciously, and think ‘that’s a great plot turn’ or ‘that would make for a great character’.”

Such is the lot of the writer: forever honouring, forever betraying those closest to them. Especially one from a minority background: the issue of what you are allowed to tell the outside world is inevitably fraught, as communities tightly police their own representation in the public sphere.

When Kochai recently went back to Afghanistan, however, people came up to the “American writer”, wanting to tell him their own stories. Often, he heard brutal accounts of war and deep personal suffering. “That was very surprising for me,” he says of their honesty, then added that “it was inspiring”.

Newsletter

Newsletter