How IV drip trend targets women of colour with ‘skin lightening’ claims

IV glutathione drips are booming on UK high streets. But behind vague promises of ‘radiance’ and ‘wellness’ lies a more sinister marketing tactic

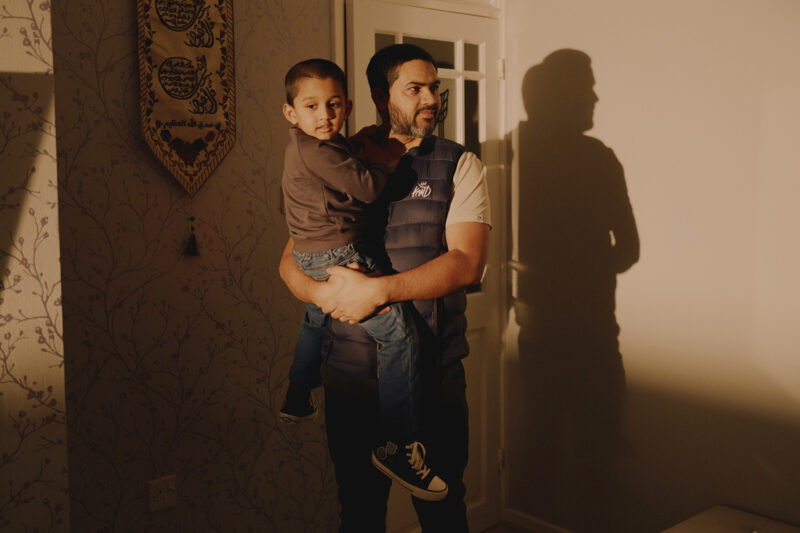

When blogger and nutritionist Asma Iqbal settles into the reclining chair of a Birmingham clinic for her intravenous (IV) glutathione drip, the soft lighting and airbrushed photos adorning the walls make the room look more like a wellness studio than a medical centre.

The British South Asian content creator has been receiving infusions of glutathione — an antioxidant often promoted for “radiance”, “even tone” and “energy” — for the past six months.

“I first had the drip because I was planning my son’s wedding, and I had so much to do and I didn’t want to get ill,” she said. “I heard it was a massive energy boost but I wasn’t aware of the skin brightening aspect until I went into the clinic.”

Iqbal said she had felt healthy and energised afterwards.

“I was so impressed that I went back a second time three months later and again just two weeks ago,” she said, adding she felt like she had had “10 cups of coffee” following the treatment.

Her social media posts about the process show how a once-niche treatment in parts of Asia and Africa is now moving into mainstream British beauty culture. But beneath the cheery language of energy boosting and “detox” used by some clinics lies a more subtle, and troubling, marketing suggestion aimed specifically at women of colour: these products can make your skin lighter.

Zara Zeeshan, 35, who lives in Croydon, London, took glutathione IV drips once or twice a month for a year. “They were marketed as quick fixes for dullness, pigmentation and stress-related skin issues,” she said. “I was curious and honestly a bit influenced by the trendiness of it all.”

But Zeeshan began to feel uncomfortable after noticing clinics using Urdu and Hindi words and pictures of South Asian models alongside messaging about “desi glow” and “brightening”. “It feels like they’re targeting women like me on purpose,” she said. “They know about the insecurities in our community and are using them to sell treatments.”

The use of coded language about the effects of the drip allows companies to exploit customers’ internalised prejudices and insecurities without scrutiny, believes Matt Dowell, marketing director for Nature Spell, a UK natural hair and skincare beauty brand.

“The skin-lightening effect is often left unspoken, with clinics framing treatments as general wellbeing,” he said. “They avoid explicit claims, instead using terms like ‘brightening’ or ‘radiance’ implying results without stating them directly and making it harder for consumers to assess risk.”

Consultant dermatologist Dr Sidra Khan says this ambiguity “sidesteps the deeper ethical conversation we need to have around colourism, body image and the pressures these messages create”.

Zeeshan said she had grown up surrounded by messaging about fairer skin being seen as more beautiful. Both she and Khan see the promotion of glutathione drips as tapping into the same prejudices.

“There’s no question that the popularity of glutathione drips for skin lightening is deeply intertwined with long-standing and harmful societal ideals that associate lighter skin with beauty, status and privilege,” said Khan, who is based in Glasgow and specialises in pigmentation. “These ideals, deeply rooted in colonialism, remain widespread, especially across parts of Asia and Africa, and continue to shape modern aesthetic preferences.”

The Chartered Trading Standards Institute recently issued a public warning after a Channel 4 investigation found hundreds of unregulated IV glutathione drips being offered in the UK with misleading claims and no medical oversight, posing significant safety risks. Other bodies echo this.

Glutathione is not licensed in Britain for either cosmetic or “wellness” use — but clinics are able to offer it by relying on legal exemptions that allow doctors to prescribe unlicensed medicines on a case-by-case basis. That means prescribers may still use it if they take responsibility for the decision and obtain informed consent. Oversight is split between multiple regulators, meaning enforcement is often slow and inconsistent.

That allows clinics to market the product for “detoxification”, “energy”, “immune strength” or “immune boost” and “cellular repair” — terms we found variously on the websites of organisations including Harley Street Skin Clinic and Continental Skin Clinic.

Market research predicts the global market for glutathione will grow by 8.8% to more than £400 million annually by 2032, its appeal being steadily amplified by celebrity use.

Khan says there is limited evidence supporting glutathione’s use for treating pigmentation concerns, and that its intravenous form is unproven and carries real risks. These include potential liver and kidney damage, allergic reactions and severe complications such as skin infections and inflammation of veins (phlebitis). There is no long-term safety data for IV glutathione.

“Patient safety must always come first and we are concerned about the growing use of unlicensed medicines like glutathione for cosmetic purposes, including skin lightening,” said professor Claire Anderson, president of the Royal Pharmaceutical Society. “There’s little evidence these treatments are effective and their safety remains unclear. These products should not be prescribed without a clinical need and using them purely for cosmetic reasons is not licensed under UK regulation.”

The pressures driving the use of glutathione go beyond any individual drug, however. “Influencers are constantly promoting products that promise ‘glass skin’, ‘instant brightening’ or ‘flawless’ complexions, which creates this illusion that perfect skin is normal and achievable if you just find the right serum or drip,” said Zeeshan.

She believes the way forward lies in naming the problem directly. “We need to talk more openly about colourism. We also need more representation of darker skin tones in media, weddings and social spaces.”

Iqbal has no regrets about the treatment, but added that discussions about glutathione should focus on health rather than appearance.

“The marketing message is very much [based] on who’s telling the story,” she said. “Is it coming from a nutrition point of view or is it coming from an aesthetics clinic?”

A Department of Health and Social Care spokesperson said in an emailed statement to Hyphen: “Work is ongoing to explore options around oversight of the non-surgical cosmetics sector.”

Newsletter

Newsletter