Zines are giving British Muslims the power of boundless expression

In recent years Muslims and marginalised communities have been forging their space in UK DIY magazine culture as a form of creative freedom

In December 2025, Khidr Collective celebrated the release of its latest zine at a community centre in Brixton. The collective shared original works by Muslim artists: a mother read out the hopeful poetry of her daughter Fatema Zainab Rajwani, one of the Filton 24. Other creatives spoke on what holding joy, the theme of the latest issue, means to them in the face of rising violence against Muslims.

Khidr Collective was founded in 2017 by a group of young Muslims who had met through student activism. “I remember things being really intense at that time — it felt like there were a lot of headlines about young Muslims in the UK doing bad things, and then everyone being tarnished,” Nadine Almanasfi, a member of Khidr, says.

“The zine was the main focus, and then also physical places where young Muslims could gather and share their work. It was a way of bringing community together and basically saying ‘fuck you’ to all the media headlines,” Almanasfi says.

People of colour continue to be disproportionately underrepresented across the British media. Yet zines — DIY, self-published, independent magazines — provide freedom for creative expression. Most often produced by an individual or a collective, no subject is too niche.

Zine-making goes as far back as sci-fi fandoms of the 1930s, but surged in the 1970s when it was taken up by punks and anarchists. Before design software and printers were ubiquitous, zines were handmade, with typewriters, felt tips and photocopiers.

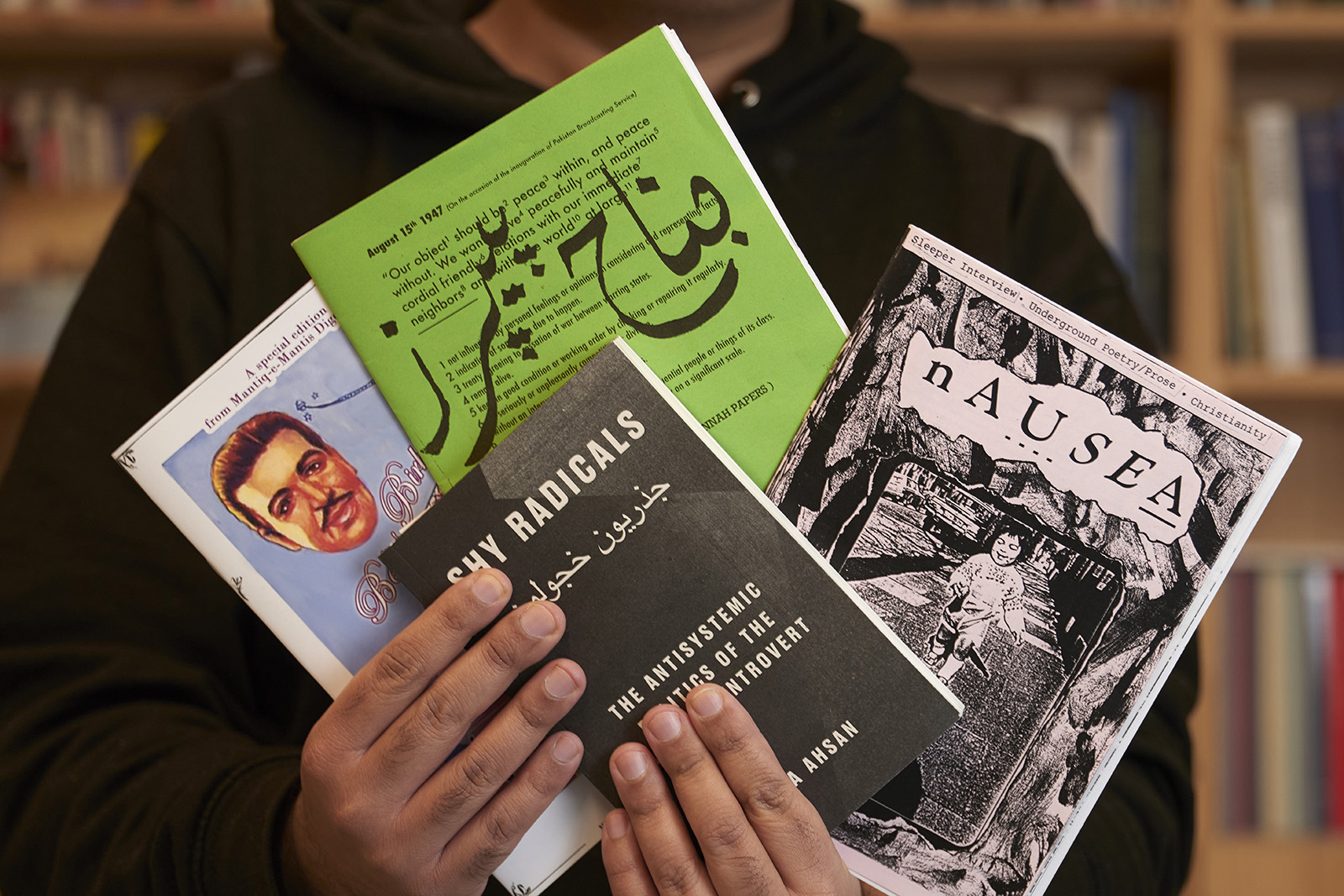

These publications allowed people on the fringes of society to express themselves without filters. “Under Thatcherism, there were a lot of anarchist and underground spaces, and people used to hand out and sell zines at gigs,” says artist and author Hamja Ahsan. “Zine culture was largest in football stadiums. In the 1980s, before the Premier League, football fans were seen the same way as the Irish or the miners — like an enemy within. Many of the football fanzines are still going to this day.”

Ahsan has been making and collecting zines since the early 1990s, with a collection now in the thousands. He curates Zine Mela, a fair that showcases works from South Asia and its diasporas.

“My entry point into zine culture was white indie music,” he says, adding that fairs at the time were largely the domain of white anarchists and “hipsters who made little effort to include local Black and brown artists”. In 2013, Ahsan co-created the zine and arts fair DIY Cultures with artists Helena Wee and Sofia Niazi to centre the stories and subcultures of marginalised people.

“I’ll meet or hear from people from Rotterdam, the United States, Malaysia, Tanzania, Uganda who were influenced by and benefited from DIY Cultures,” Ahsan says. “It revolutionised the makeup of the culture.” On the closing day of the final fair in 2017, Ahsan estimates that some 2,000 visitors moved through the multi-storey exhibition space in east London.

Brighton-based illustrator and zine-maker Soofiya was also inspired by DIY Cultures and believes community is at the heart of zine-making. Zines are a “culture and way of thinking — you can just make a zine and get your ideas out there and collaborate and do so much with no institution needed to make that happen,” they say. “Then there is community. I run a zine club, and there are zine fairs that run across the UK and internationally.”

For that reason, this form of creativity is especially important for Muslim and other minority groups, says Almanasfi. “It’s really important that community is still a physical thing and people are meeting and talking — that’s how artistic, political, and social connections are built,” she says.

Munaza Kulsoom is one of the organisers of the Bradford Zine Fair. “A lot of the core of zine-making is: why do you feel like you need permission, and why do you need a publisher to sign off and tell you that you are worthy of print? I try to contribute to the landscape in a way that feels different, to platform people of colour or those who are doing something more transgressive,” she says.

“There have been a few moments of South Asian women coming up to me, shocked that I was running the event and asking how I had gotten into it. It hadn’t occurred to me how important it was for someone who looks like me to be running a zine fair.”

Bradford local Afzal Khan’s work includes the zines The Masjid Uncles of the Front Row and Aapne, a zine-photobook documenting British-Pakistani cyberculture of the early 2000s.

“Seeing zines created by people in Bradford was quite a powerful experience. It definitely did inspire me to create my own,” Khan says.

“The zine format lets me say what I want, and I’m not censored by anyone. I don’t answer to anyone in my work; it’s just me and the small audience I’ve created.”

Newsletter

Newsletter