All That’s Left of You: moving drama is an epic tale of a Palestinian family over generations

Cherien Dabis’s ambitious film doesn’t aim to explain history so much as to show how its scars accumulate

Cherien Dabis’s All That’s Left of You is an ambitious and contemplative tale about a subject that cinema has rarely treated with such scope: how the Israeli occupation of Palestine shapes not just political realities, but ordinary family dynamics across decades.

Following three generations of a single family over 80 years, the film doesn’t aim to explain history so much as to show how its scars accumulate. How moments of fear, compromise and loss quietly stack up until they become unbearable.

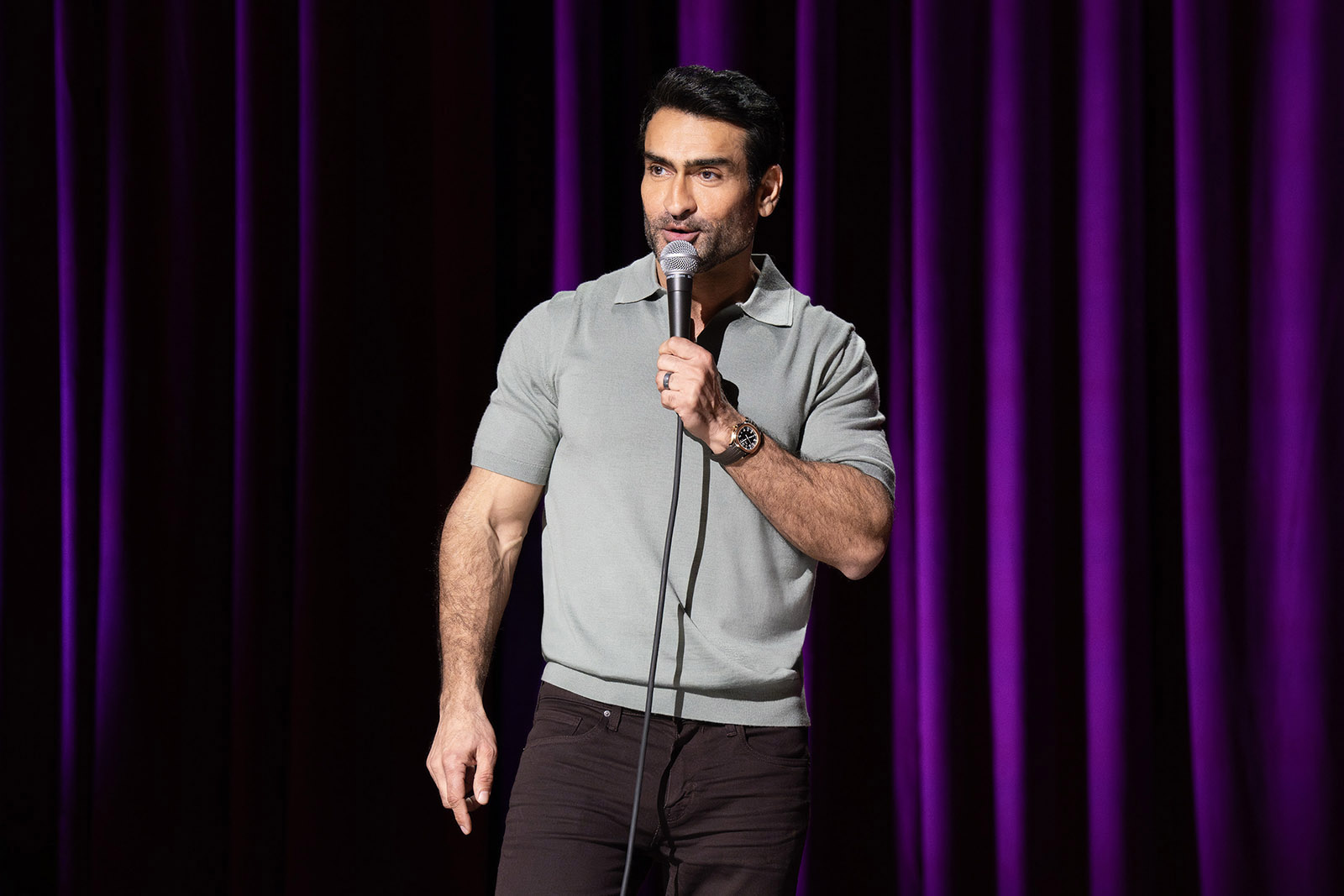

The Palestinian-American director and actor has been heralded as one to watch ever since the release of her 2009 Sundance darling Amreeka. She’s since turned her hand to comedy and television, directing shows such as Ramy and Ozark. Dabis was nominated for an Emmy for her work on an episode of Only Murders in the Building while still finding time to act in projects such as Netflix’s acclaimed sitcom Mo. Her latest film sees her as the official Jordanian entry for best international feature in the upcoming Oscars.

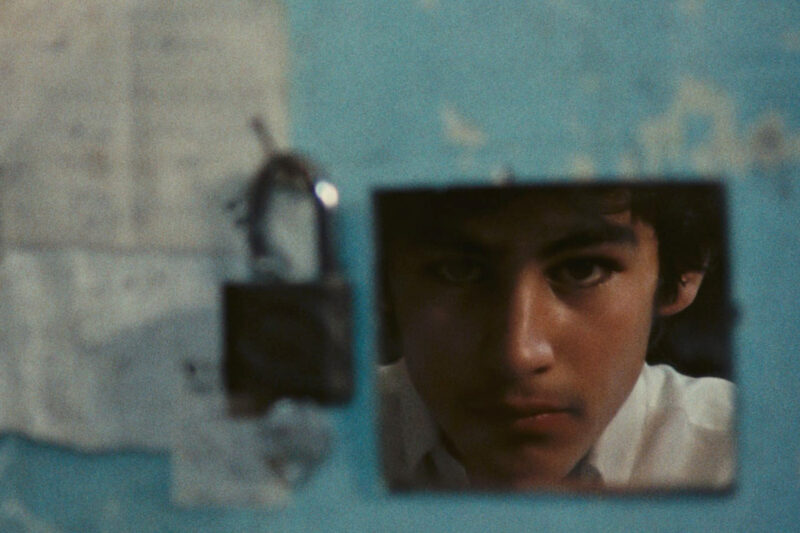

The opening scene of All That’s Left of You drops us in the West Bank in 1988. A teenage boy, Noor, joins a street protest almost on a whim. When soldiers open fire, he dives into a parked car and a bullet smashes through the windshield. The film cuts away before we learn what happens next. Instead, Noor’s mother, Hanan (played by Dabis), looks directly at the camera and tells us that if we want to understand her son, we first need to understand his grandfather. It’s a bold framing device, but also a practical one: this is a story about far reaching causes and effects, and how long trauma can last.

The film rewinds to Jaffa in 1948, where the grandfather, Sharif, lives a comfortable life with his family. He loves poetry, tends his orange grove, and believes that staying put is an act of dignity. As violence closes in, Sharif sends his wife and children away but remains behind to protect what he thinks can still be saved. But it simply cannot. His arrest, imprisonment and eventual displacement form the emotional bedrock of the film, even when he’s no longer on screen.

Dabis tracks the family through the years that follow, with most time spent in the 1970s when Sharif’s son Salim is raising Noor under occupation. Their relationship sits at the heart of the narrative. This section is where All That’s Left of You feels most alive. Dabis pays close attention to the texture of everyday existence: the tension of curfews, the claustrophobia of shared living spaces, the small pleasures people cling to when bigger dreams aren’t possible. A wedding scene, full of music and warmth, briefly pushes back against the film’s prevailing heaviness by reminding us that the ability to feel joy cannot be completely stripped away.

The performances are sensitive and exquisite. Saleh Bakri (Palestine 36, The Teacher) is particularly strong as Salim, conveying the exhausting strain of a man trying to keep his family safe in a system designed to keep him terrified. Adam Bakr (Omar, Official Secrets) brings warmth and intelligence to the younger Sharif, while Mohammad Bakri (Wajib), playing him in later life, embodies the bitterness of a man who has outlived the world he believed in. Dabis is restrained as Hanan, reflecting a character who has learned to live in a near constant state of grief.

At close to two and a half hours, All That’s Left of You does occasionally feel like it’s carrying more than it needs to, and the film’s desire to mark specific historical moments can make the pace sluggish at times. The 1988 section, in which Noor becomes politically active, sprints forward, conversely leaving him slightly less developed than the adults around him. Yet these are more the trade-offs of an openly ambitious project than flaws.

Without tipping into maudlin sentimentality, All That’s Left of You finds space for tenderness and moral complexity, allowing its characters to be three-dimensional people rather than symbolic victims.

What ultimately distinguishes All That’s Left of You is its refusal to flatten experience into easy lessons. It doesn’t present resistance as straightforwardly heroic or submission as inherently shameful. Instead, it shows how both can exist within the same person, often at the same time. Dabis understands that survival under occupation contains multitudes and that judging it from a distance is a position of privilege.

This is a demanding film and not a comfortable watch. In choosing to tell Palestinian history through family memory rather than spectacle, Dabis makes a disquietening and persuasive case for why these stories matter — not as background to headlines, but as lives shaped daily by forces beyond their control.

All That’s Left of You is in UK and Irish cinemas from 6 February.

Newsletter

Newsletter