The hijab was never meant to be a brand or performance, but a symbol of faith and belief

Social media is full of images of hijab-wearing women conforming to certain beauty standards. For World Hijab Day on 1 February, we should remember its true meaning

When I first decided to wear the hijab in 2023, I learned the meaning behind Allah’s commandment for me to wear it. I fell in love with it instantly. Throughout my journey, I explored different styles and fabrics that I felt comfortable with. Lightweight modals, slick jerseys and my favourite style, the silk bandana tied over chiffon. My relationship with the hijab has always felt like an extension of who I am. It anchors my identity.

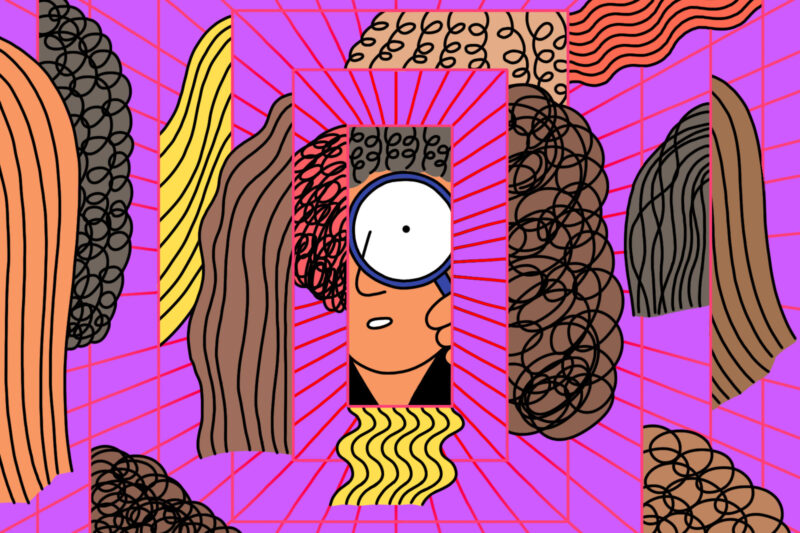

But recently I’ve seen a particular archetype appear across Instagram and TikTok feeds: the “pretty hijabi”. Lately, social media has been full of images of Muslim women posing in the most expensive printed hijabs, accessorised with viral it-bags. This aesthetic requires money and styling, when really the hijab is functional and spiritual. It deserves legitimacy. Instead of being viewed as a marker of faith it appears, for some, to have become a curated performance.

For World Hijab Day on 1 February, we should ask how a practice rooted in intention and modesty has become entangled in the relentless aesthetic economy of social media.

We know that algorithms favour faces that fit conventional beauty standards. But this feels particularly problematic when it comes to the hijab, a garment that’s meant to shift attention away from the body instead of amplifying it. The rewarding of images of women who fit a certain beauty standard by social media platforms reinforces societal expectations of what a presentable hijabi should look like, narrowing how Muslim women are seen online.

I’ve even found myself unconsciously conforming to this culture of modest consumerism, clearly shaped by what I see online. I have scrolled through ads showing Vela scarves and my wardrobe is full of bags and printed, coloured hijabs.

Speaking with other hijab-wearing friends, we all experience similar pressures to compensate for covering up by wearing a lot of makeup, styling a colourful printed hijab or completing our looks with designer accessories.

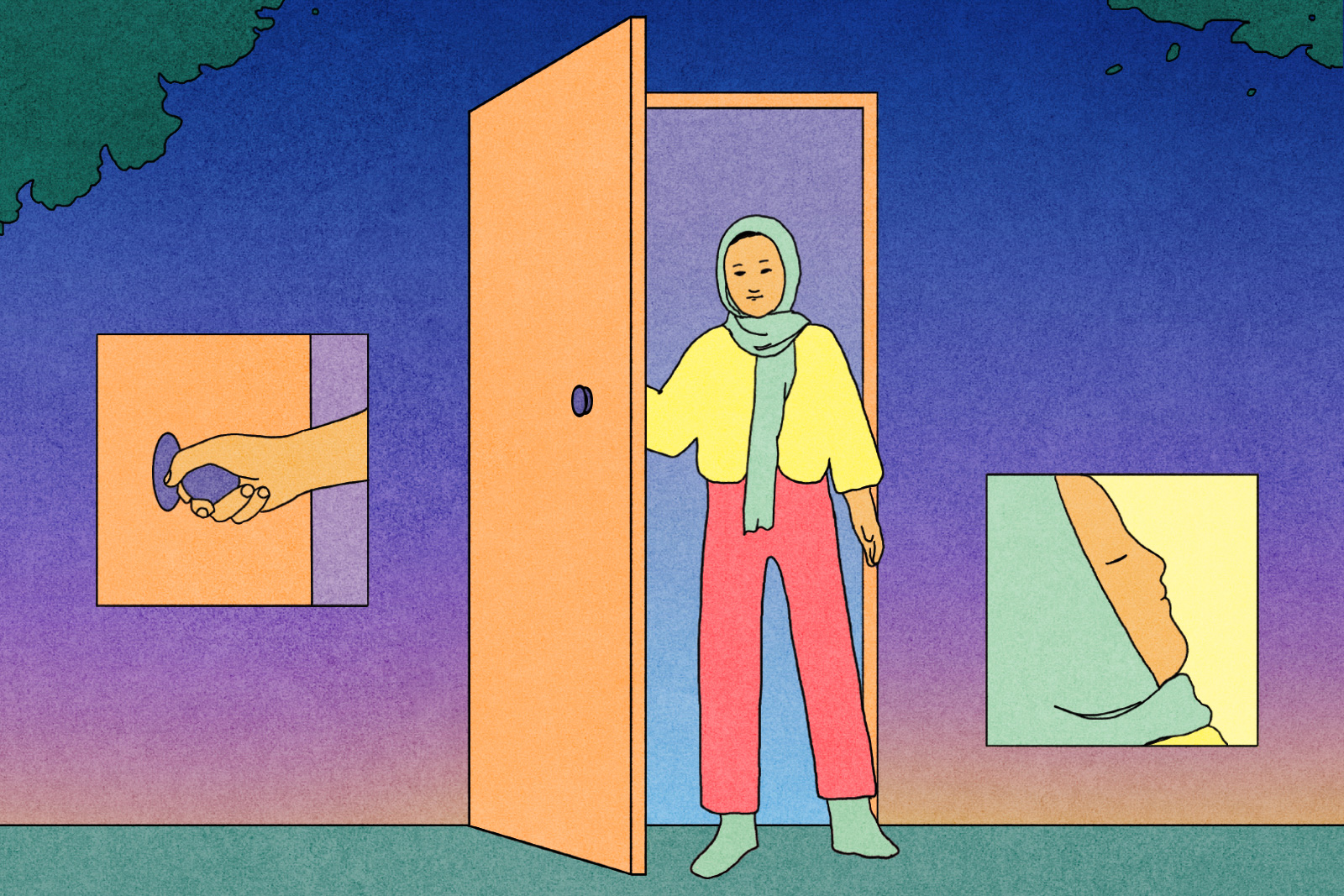

But maintaining a public-facing version of the hijab can be exhausting. Some hijab-wearers feel a growing disconnect between how their faith feels and how it is displayed. In chasing affirmation, we risk being pulled further away from the private, intentional act many women describe when they first choose to cover. What remains is a version of a hijab that is highly visible but not always deeply understood.

The pressures to appear confident and fashionable at all times can undoubtedly lead to low iman. When my iman fluctuates, it’s never the hijab that’s the problem — I’ve always held on tightly to why I wear it and what it represents. But I still feel the weight of expectation that social media perpetuates, as if the garment that initially grounded me spiritually has been turned into another beauty standard.

Wearing the hijab is a personal journey. My relationship has survived doubt because it was never built on trends or validation. In the face of these social media-driven pressures, I must endeavour to remember that. I don’t have to be palatable to everyone. The work now is to return to the roots of Islamic practice. The hijab was never meant to be a brand, a material or a public performance, but instead a symbol of faith and belief.

Newsletter

Newsletter