As the Tories lose MPs, Badenoch reckons she can beat Farage at his own game

The Conservative leader has given short shrift to a trio of big names leaving her party for Reform UK. Will her strategy work?

There is a defiance in Kemi Badenoch’s approach to crisis management. Where other political leaders might have sought to steady the ship, extend olive branches or quietly shore up wavering colleagues, she has chosen a different path entirely: double down.

Three such high-profile defections in a fortnight is virtually unprecedented. For many opposition leaders, the loss of figures such as Nadhim Zahawi, Robert Jenrick and Suella Braverman, all now wearing Reform UK’s colours, could have been seen as a fatal haemorrhage of political capital.

But Badenoch, particularly in her speech this week, used their exodus to make some political capital of her own. The defectors, she said, were engaged in a “tantrum dressed up as politics” and the Conservative Party was better off without them.

When I sat down with her for ITV News on Wednesday and asked whether she expected more to follow her former colleagues out the door, she did not hesitate. “Of course there will be some people who I can tell are unhappy,” she told me. “So it wouldn’t be a surprise.”

It was a stark assessment. But Badenoch has made a clear calculation: let those who want to leave go and then take on Reform not by retreating to the centre of British politics but by confronting them head-on, on their own terrain.

That choice has shaped both tone and tactics. The Conservative response to defections has been aggressive. When Zahawi joined Reform, senior Tory sources briefed journalists about his alleged attempts to secure a knighthood — something he denied. With Jenrick, Badenoch moved first, sacking him before he could quit, while party sources circulated his resignation speech to reporters moments before he was due to deliver it. And when Braverman left, the initial response included a reference to her mental health — a comment seen as so below the belt it was hastily retracted within hours.

Taken together, it is clear Badenoch and her team are not graciously waving departing figures off. Instead, they are going on the attack as they attempt to reclaim the right-wing vote.

Her policy platform is comparable to Reform’s core offer: opposition to net zero targets and pledges to reduce immigration sharply and withdraw from the European Convention on Human Rights. Badenoch is betting that voters tempted by Reform’s clarity and confidence can be persuaded they do not need to abandon the Conservatives to get it.

That strategy also explains her explicit rejection of the centrist project launched by Andy Street and Ruth Davidson this week. Their Prosper UK movement claims to have identified seven million “politically homeless” voters who feel unrepresented by current parties. Badenoch was unimpressed. She reminded colleagues that she is the leader, and the agenda she sets is the one that matters. Anyone pulling in a different direction, she said, “is not being helpful”.

Privately, some centrist MPs disagree. Davidson once rebuilt the Scottish Conservatives into a credible force; Street was seen as being among the most successful Tory metro mayors in the country. Their brand of pragmatic, economically focused, socially liberal conservatism now appears to be homeless within a party that has decided survival depends on consolidation, not compromise. As one pro-Badenoch MP put it to me bluntly: “They did so badly that Reform are now doing well, so I don’t think they’re the answer.”

Yet Reform’s rise brings its own questions. While Nigel Farage has repeatedly declared the Conservative Party to be “dead”, it is polling third, is still the official opposition and has experience of winning elections and governing.

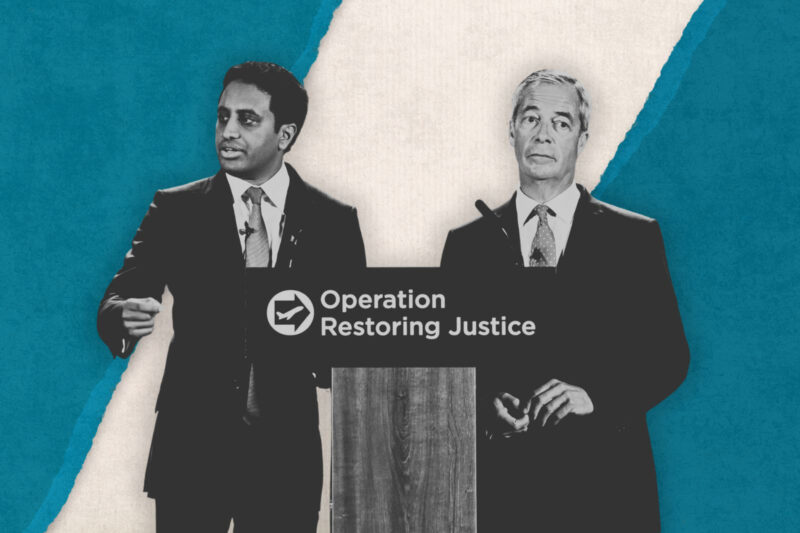

That has partly influenced Reform’s decision to accept defectors. I have attended each of the press conferences unveiling Zahawi, Jenrick and Braverman, and at the most recent I asked Farage whether the party could still plausibly present itself as an insurgent alternative to mainstream politics while welcoming former Conservative cabinet ministers.

His frustration was evident. “I can’t win,” he replied. “If we’re a group of people who’ve never been in politics before, you say we’re a bunch of nobodies with no idea what we’re doing. If we recruit people with genuine experience at cabinet level, you say we look like all the others.”

Having spoken to both leaders this week, it is striking how similarly they frame the stakes. Each believes they are fighting for the future of the right, not just to win votes but to define what conservatism now means. Both are convinced that, in the end, only one of their parties will endure as its standard-bearer. They are both very willing to fight to get that role.

Shehab Khan is an award-winning presenter and political correspondent for ITV News.

Newsletter

Newsletter