Wonder Man: one of the bravest moves Marvel has made in years

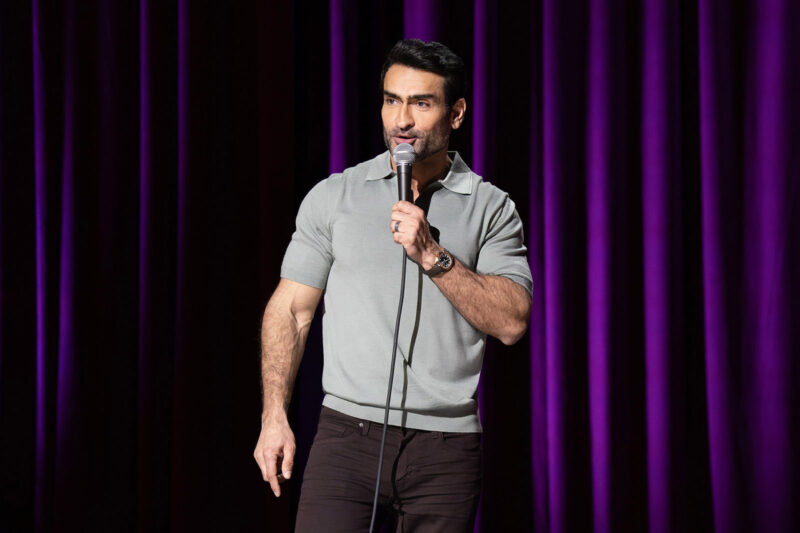

Ben Kingsley and Yahya Abdul-Mateen II star in the new Disney+ series as two struggling actors in a deeply flawed film industry

The series Wonder Man arrives as the Marvel Cinematic Universe (MCU) is running on fumes. The Fantastic Four failed to generate much enthusiasm and the TV franchises have struggled, with most lasting a single, soon forgotten about season.

Aside from an undying enthusiasm for all things Spider-Man, I am personally not just in a state of Marvel fatigue. I have entered a Marvel coma. But against those odds, Wonder Man on Disney+ has emerged as a glorious return to form, the best since the golden era of WandaVision.

Rather than contorting the fabric of reality, Wonder Man turns inward. Its subject is performance — who gets to perform and who is punished for performing too much. Through this approach it becomes one of the MCU’s most salient projects; a show more interested in labour, identity and the violence of justice for profit, than typical heroism.

The series centres on two struggling actors: Simon Williams (Yahya Abdul-Mateen II) and Trevor Slattery (Ben Kingsley), both pursuing roles in a remake of a superhero film also titled Wonder Man. Slattery is best known as the hapless fall guy in Iron Man 3, who was hired as an actor by a criminal organisation to portray terrorist leader the Mandarin, oblivious to their actions. Slattery was arrested and imprisoned in the previous film and, in Wonder Man, is now living as a government asset, having traded freedom for cooperation. His handler (played with unsettling calm by Arian Moayed) represents the Department of Damage Control, an organisation revealed to be entangled with the prison-industrial complex.

Williams is a gifted actor, perhaps too gifted for his own good. A decade into trying to make it big he approaches every role with a level of intensity that borders on mania. He’s fired from a small part on American Horror Story for overthinking his minor character’s backstory.

Despite the dark humour found in his pretension and subsequent failures, Williams’ story becomes a tragic tale of a flawed industry that rewards efficiency over depth. Complicating matters further are his blossoming superpowers. In moments of high emotion things tend to explode, but he has no interest in being a superhero, he just wants to play one on screen.

Slattery remains one of the MCU’s more compelling figures, precisely because he is a performance of a performance. Oscar-winner Kingsley breathes complex life into this reformed hedonist who sincerely delivers self-aggrandising lines such as: “Acting is not a job, it’s a calling. It’s the single most consequential thing you can do with your life.” Kingsley brings across the character’s insecurities and slipperiness without asking the audience to absolve him. His chemistry with Abdul-Mateen is delicious and heartbreaking. Slattery understands, perhaps better than anyone, how much you may need to sacrifice to make it in Hollywood.

Meanwhile, Moayed is the series’ most chilling presence as the face of a cruel governmental institution. He never raises his voice, yet his calm efficiency embodies the justice system’s amorality.

The show’s most incisive invention is the “Doorman Clause”, a fictional Hollywood regulation that makes it illegal for individuals with superpowers to work in film. Absurd at face value, the rule functions as a devastating allegory of a bureaucratic mechanism that codifies exclusion while claiming to ensure fairness. For Williams, it means hiding an essential part of himself in order to work at all.

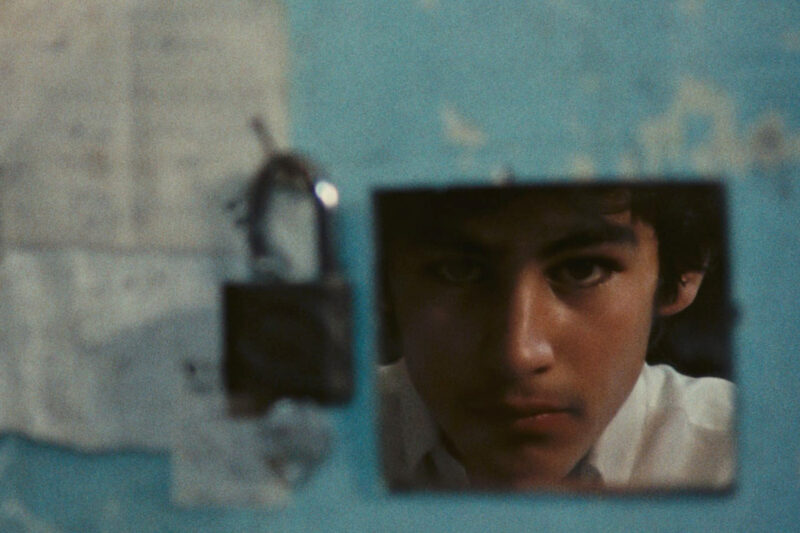

Episode four, led by the astonishing comedian Byron Bowers and featuring a delightful cameo from Frozen star Josh Gad, traces the origins of that clause. Shot in black and white, it is hilarious but deeply unsettling, revealing how moral panic, corporate liability and state power conspire to shape culture and squeeze every drop out of those with a little cachet.

That three of the show’s central performers — Abdul-Mateen, Kingsley and Moayed — have a shared Muslim heritage enriches the piece. Though Wonder Man isn’t a Muslim story — Abdul-Mateen’s character is explicitly Haitian and speaks Creole — it is deeply informed by questions familiar to Muslim and other minoritised artists: legibility, respectability and the price of refusing to soften oneself for institutional comfort.

Abdul-Mateen’s casting carries textual weight. Early in his career, he was explicit about not changing his name or adopting a stage persona to make himself more palatable to an Islamophobic industry, a decision that quietly reverberates through Williams’ arc as being othered within his chosen career.

In an industry increasingly hostile to seriousness, Wonder Man dares to ask what it means to care deeply. The series succeeds beyond the many superhero shows that preceded it because it understands that art is never neutral. Who gets to be seen and believed on the silver screen are political questions. Wonder Man gestures toward a version of Marvel storytelling that portrays much more than corporate synergy and American exceptionalism. It is one of the bravest moves the MCU has made in years.

Wonder Man is streaming on Disney+ from 28 January.

Newsletter

Newsletter