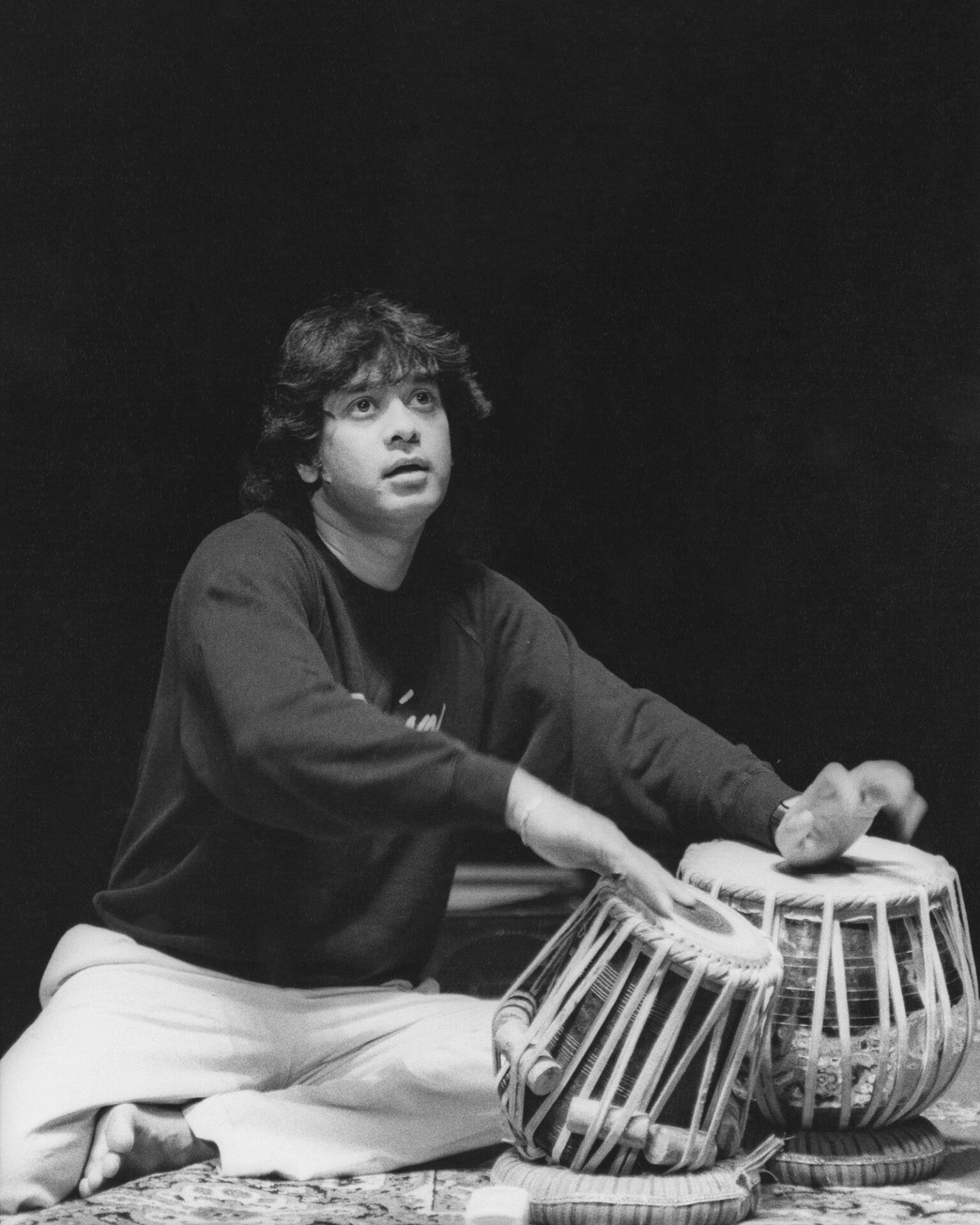

‘He lives on each time someone strikes the drum’: the legacy of tabla player Zakir Hussain

One year on from his death, the master musician’s collaborators and family members remember the enduring power of his artistry

By turns frenetically fast and hulkingly heavy, yet somehow nimble and tender, tabla player Zakir Hussain’s percussive sound was one of a kind. Over the course of his five-decade career, Hussain was renowned globally for his capacity to blend Indian classical tradition with jazz, electronica, folk and psychedelia.

Bestowed with the honorific of Ustad, meaning a master of his craft, Hussain collaborated with artists across genres, from West Coast psychedelic pioneers the Grateful Dead to George Harrison, banjo player Béla Fleck and jazz saxophonists Pharoah Sanders and Charles Lloyd.

He founded the jazz fusion group Shakti with guitarist John McLaughlin and the electronic-influenced group Tabla Beat Science with producer and bassist Bill Laswell, ultimately earning nine Grammy nominations and four wins for his boundary-breaking sense of creativity.

One year on from his death in 2024 at 73, the musical gap left by his passing remains unfilled.

“His influence has been infinite,” Hussain’s brother Fazal Qureshi says. “We have different schools of classical music tradition in India, called gharanas, and he belonged to the Punjab style of playing tabla but throughout his career he was so wide-ranging that he managed to unite all the gharanas. Today’s tabla players now can’t perform without playing Zakir’s style.”

Born in Mumbai, Hussain and Qureshi were raised in a tabla-playing dynasty. Their father, Alla Rakha, was a frequent accompanist of sitar player Ravi Shankar and was one of the first musicians to spread the sound of Indian classical music to western audiences.

“Our education from our father was constant,” Qureshi says. “Sometimes he would remember a composition at the dining table while we were eating and we’d have to stop so he could teach it to us. The tabla was always resonating and we began performing from a very young age.”

Hussain began taking formal tabla lessons at seven years old and in 1963, at the age of 12, he began touring domestically with his father. Influenced by tradition as much as the sounds of the Doors and Jimi Hendrix, Hussain considered switching to the drum kit after graduating from college. But a conversation with his father’s friend, Harrison, persuaded him otherwise and led him to relocate to San Francisco in the late 60s to pursue what would become his signature fusion of Indian classical and western music.

In his early 20s Hussain lived with Grateful Dead percussionist Mickey Hart and developed his musical language during extended jam sessions that could last two days or more at a time. After featuring on Hart’s debut solo album, Rolling Thunder, in 1972 and playing on Harrison’s record Living in the Material World the following year, Hussain became friends with jazz guitarist McLaughlin and joined his group Shakti.

“We all became aware of his playing in Shakti and it felt like psychedelic music when you heard them live since it was so free and full on,” says Laswƒlaswellell, another of Hussain’s many collaborators. “You could tell Zakir was an incredible musician, his technique was ridiculous and he had such an innate sense of rhythm and time. He could play with anything and anyone and he was never conscious of it, it was natural.”

An early example of Indo-jazz fusion, Shakti went on to develop a loyal following and an intricate sound that wove together McLaughlin’s finger-picking guitar melodies with Carnatic violin playing and Hussain’s signature torrents of rhythm. Shakti’s debut, self-titled album in 1975 was renowned for its combination of jazz improvisation with Indian classical instrumentation, blending the violin with the mridangam and ghatam drums of south India.

Hussain continued to pursue this sound throughout his life, most recently in 2019 in his Triveni trio with south Indian violinist Kala Ramnath and north Indian veena player Jayanthi Kumaresh. “When Zakir called me in 2018 and said he wanted to create a group that united the musical traditions of India, I said yes immediately,” Ramnath says. “It wasn’t your usual jugalbandi [Indian classical duet], instead it was like three rivers flowing continuously for an hour and playing one singular music.”

“The project encompassed several firsts,” Kumaresh adds. “It was the first time you had an Indian classical master travelling and playing with two female instrumentalists and it was the first time you had a western instrument, the violin, playing a south Indian style alongside the veena playing the north Indian Carnatic tradition. Only Zakir had the power and virtuosity to bring it all together.”

His collaborators emphasise that Hussain held his talent and the responsibilities of tradition lightly. “As much as there is a colossal lineage, he always made the music friendly thanks to his constant trust and casualness,” Hussain’s frequent mridangam accompanist Anantha Krishnan says. “He showed us that tradition isn’t overbearing and it doesn’t need to be so serious.”

Laswell, who collaborated with Hussain in the early 2000s as part of Tabla Beat Science, a percussive supergroup that combined the nascent electronic maximalism of drum’n’bass with tabla tradition, echoes the sentiment. “He was incredibly humble and he wouldn’t accept the Ustad title or people bowing to him,” he says. “He was with the audience and he always brought so much humour to everything. He wasn’t precious.”

Laswell remembers playing a festival show in Japan and letting Hussain know on their way to the venue that the crowd wouldn’t be aficionados, but rather kids looking for a good time.

“I told him we were about to play to 10,000 people on drugs wanting something heavy,” Laswell says. “He brought a bucket of ice onstage, held his hands in it for a while to get them numb and when he took them out he played the tablas so hard it was incredibly powerful. He was always ready to adapt and so intense on stage.”

It’s a deep shame, Laswell says, that new audiences will not be able to experience Hussain’s artistry in person. “Zakir had to be seen to be believed and I just hope enough people had that chance. I’m still in shock he’s no longer here, I just thought he’d live forever. When people ask me who the best musician I ever worked with is, I always say Zakir Hussain.”

Qureshi sees Hussain’s virtuosity living on through his recorded music and in groups such as Triveni, which has expanded to see Qureshi take his brother’s place, as well as adding Krishnan to the group. “I feel his presence every time we play and it’s a big responsibility to do justice to him,” Qureshi says. “He gave a new dimension to music and whenever you hear a tabla player now, I hear Zakir. He will live on each time someone strikes the drum.”

Newsletter

Newsletter