The south London chef introducing Berlin to real South Asian food

Shabnam Syed is winning over German diners with the dishes her mum and aunties made

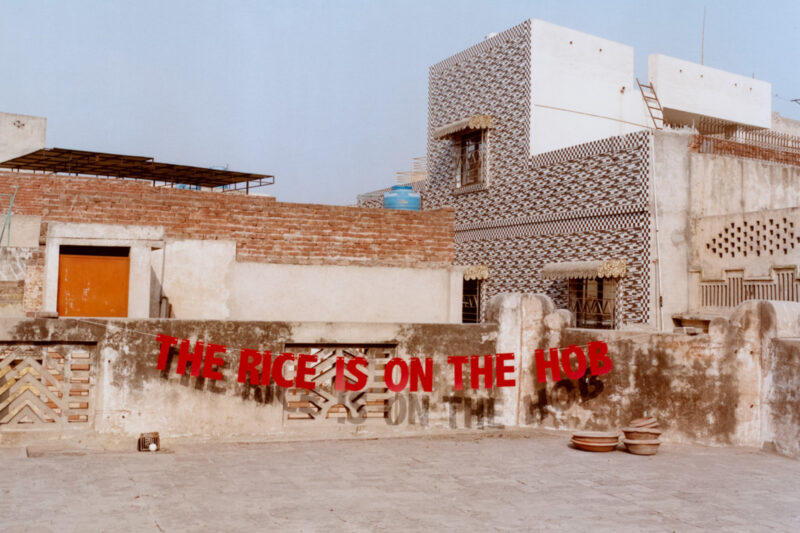

Shabnam Syed’s mission to revolutionise the South Asian food scene in Berlin started with a piece of Mexican flatbread. When the British-Pakistani restaurateur moved to the German capital from London in 2014, she went to an Indian restaurant, asked for a roti and was given a tortilla. “I was like, ‘Is this the representation our cultures are getting?’ It gave me the push I needed.”

A decade later, Syed has opened and closed a restaurant, launched the catering company Mama Shabz and opened Desi Diner, a popular, pastel-coloured breakfast and lunch joint serving a fusion of Pakistani street food and British comfort dishes. Local media have referred to her as “Berlin’s premier Pakistani chef” and crowned the diner the best breakfast and lunch opening of 2024. Her food has been mentioned everywhere from hipster blogs to glossy international magazines.

Syed is building a small food empire on the meals her mum and aunties cooked for her, determined to introduce authentic regional cuisine to a country infamous for its conservative food tastes. As renowned restaurant critic Wolfram Siebeck once told the New York Times, ‘[German] People prefer their food to be mild. That’s something that gets me on the barricades, because mildness in food — it’s a castration.” Syed agrees that almost all immigrant cuisines have watered themselves down to adapt to the German palette, particularly South Asian — until she came along.

The 39-year-old culinary entrepreneur grew up in Peckham, south London. Every Friday, her mum hosted potluck dinners with her friends and aunties. “I was always fascinated by the different versions of dishes people made,” she said. “I had an auntie from Malawi and she would bring their version of biryani, and I loved seeing how recipes were similar yet slightly different.”

Syed trained and worked as a social worker, but after nearly a decade in the job, longed for a change. Attracted primarily by the music scene, she decided to try Berlin and accepted a job as a nanny there. She loved living in the city but struggled to find decent South Asian food. Most restaurants, like the tortilla-serving Indian establishment, served inauthentic dishes using the wrong ingredients. She was struck by how few women were working in those restaurants. “In London too, most of the South Asian restaurants are owned by men,” Syed said. She felt a strong need to right these wrongs.

To celebrate her first birthday in the city, Syed threw a big picnic for her new friends and cooked her childhood favourites, including pakoras and chana chaat. They adored her food, which to many of them was totally new. One suggested she do a pop-up event at the bar where they worked part-time. She did, and it was a huge hit. “It all took off from there,” she recalled. More pop-ups followed, then stalls at festivals and other big events.

Syed set out to write down her mum and aunties’ recipes — a bigger challenge than she expected. “They just go with their intuition,” she said. “I had to literally stand next to my mum and measure everything she was doing, and she hated it.” Another issue was supplies: authentic spices are not as easy to come by in Berlin but Syed eventually found a Pakistani-run store in the western Moabit neighbourhood, which supplied her with everything she had missed.

In 2018 she was offered a permanent stall at Berlin’s renowned Markthalle Neun street food court. She was surprised at the wide range of people who became her regulars, from British expats searching for decent curry, to curious Germans and Pakistanis excited that someone was serving their favourite dishes from home. “So many people would turn up and I’d be like ‘Where did you all come from?’” she laughed. “I had no idea just how many Pakistani people were in Berlin.”

The family Syed nannied for were supportive, allowing her to work flexibly until she was in a position to support herself entirely through her food. In 2020 she opened her first restaurant — also called Mama Shabz — in the Kreuzberg district. Pictures of her family matriarchs adorned the walls and she trained up staff to make her mum’s recipes. Reviewers praised the authentic dishes and colourful, homely ambiance, but after four intense years — spanning the Covid pandemic — she welcomed her first baby a year ago and decided to close the restaurant so she could devote more time to mothering. In late 2024, she opened the Desi Diner in a friend’s canteen-style space in Neukölln. The menu fuses Pakistani dishes with some of her British childhood favourites, such as toasties. This venture too has been praised by food critics for having an “exciting and surprising” menu that’s “an absolute must in Berlin for anyone who fancies an extraordinary taste experience”.

As Berlin’s economy improved over the past decade, driven largely by a tech industry that has attracted workers from all over the world, the restaurant scene has become more varied and diners have become more adventurous. Improved global supply chains have also made it easier to source ingredients. “There’s definitely more Indian and Pakistani restaurants now, and they’re being run by people actually from those countries,” Syed confirmed.

But a difficult more recent economic climate — Germany is now in its second year of recession — is particularly challenging for business owners from ethnic minorities. Rents and overheads are rising and people are eating out less. “Okra was one of my favourite ingredients, but it doubled in price during the pandemic so I had to stop serving it,” Syed said.

It’s undoubtedly a challenging market, but Syed is committed to her cause. She is no longer a practising Muslim but is keen to recreate the community feeling she grew up with. “I have such fond memories of coming home from school and sharing a meal with people who you love,” she said. Last Ramadan, she threw her first iftar event. “We had people who were fasting, people who were not Muslim and were just curious, and people who were Muslim but not fasting.” It was such a success, she is planning to do more community events.

But first, she wants to go to Pakistan — an educational trip to learn new regional dishes and techniques. “My plan is to do a food trip to the north, where the food is less spicy and more aromatic,” she said. “There are such huge variations between the different regional cuisines of India and Pakistan, but in Europe there’s still not much awareness of the differences between them all.”

Newsletter

Newsletter