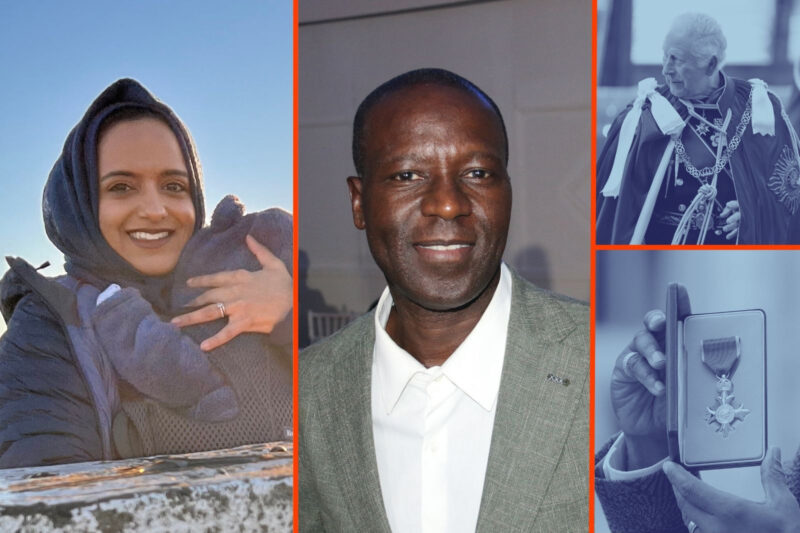

Muslim war memorial: government delay forces trust to find £1m elsewhere

Long-awaited project could help counter far-right myths about Muslims not being part of Britain’s history, argue supporters

The World Wars Muslim Memorial is seeking funding from the National Lottery and other donors to build a memorial to Muslim veterans after £1m pledged to the project by the government in 2024 failed to materialise.

“We still hope that the government will stay true to its word,” said Sir William Blackburne, chair of the memorial’s trustees. “In the meantime we are developing plans to raise what we need privately, but that is not an easy exercise.”

Tony McClenaghan, another trustee, added: “It is now 18 months since the chancellor of the exchequer at the time, Jeremy Hunt, announced a £1m donation to the memorial. We are in the process of applying for National Lottery funding, but whether we get it — that is anybody’s guess.”

The proposed memorial would honour Muslims who served with Britain and its allies in the two world wars as well as British Muslims who have died in combat more recently. It would be located within the National Memorial Arboretum in Staffordshire.

Hunt pledged £1m in funding to cover all expenses for the proposed memorial in March 2024. After the Labour government came into power later that year, it confirmed it was still committed to funding the project, Blackburne told Hyphen. More than a year later, however, the money has not materialised and the trust has confirmed it is now looking for private funding.

In September, the government told the BBC that it was developing plans to put up to £1m towards a “fitting Muslim War Memorial” but did not specify if it would be the one proposed by the trust.

About 1.5 million Muslims fought in the British Indian Army (BIA) during the two world wars.

Although the 2014 centenary of the first world war sparked renewed interest and debate regarding the forgotten contribution of the BIA to the war effort, public awareness is still low, said Steve Ballinger from the thinktank British Future.

According to a recent poll commissioned by the organisation, just over half of Britons were aware that Indian soldiers served in the second world war, and only a third were aware that Muslims had served.

“I think over the last 10 years there has been an effort to make Remembrance look more inclusive and improve the optics a little bit, but we can’t just leave it to the government,” said Ballinger, who has spent a decade working on the thinktank’s project Remembering Together to raise awareness of BIA war contributions. “It has to be a whole-society effort.

“Once, as part of the project, I took schoolchildren from Walthamstow to the local cenotaph on Remembrance Sunday and we’d secured permission to actually lay a wreath that the students had made. But they were some of the only non-white faces there.”

“Memorials do genuinely contribute to the way people remember the past,” said Meghan Tinsley, a senior sociologist at the University of Manchester who researches British memory politics. “Most war monuments that are in town squares or churches list the names of dead soldiers from that town or parish. So the names that we came to associate with those who died in the war are very white British names — but that’s not a very accurate representation.”

Tinsley said that the British public would have been aware at the time that Indian soldiers were fighting in the trenches during the first world war, but that this narrative had been sidelined following the armistice as it was seen as diminishing Britain’s prestige in victory.

She added that a memorial could help counter far-right claims about Muslims.

“If Muslims are presumed to be a new presence in Britain with no history, that enables far-right narratives to be adopted by the public. Those narratives often centre on ideas of who ‘contributes’ to the nation or who ‘deserves’ to be here,” she said. But she also warned: “Centring the memory of British Muslim history on, say, the Muslim Victoria Cross winners creates a standard of what a ‘good Muslim soldier’ looks like, and risks implying that those who don’t live up to that standard do not belong.”

McClenaghan said: “The hope is that having a memorial in a prominent site will raise awareness among the public of the role that the Muslims played in the wars. It wasn’t simply a Muslim contribution — they were part and parcel of a mixed army of all the races and groups there — but they played a very prominent part.”

The Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government did not reply to a request for comment.

Newsletter

Newsletter