‘Commemorating all those who served brings people together’

Campaigners hope greater awareness of the efforts of Muslims and people of colour in the first and second world wars can help build unity in Britain today

–

Mohammad Hussain was 16 years old when he ran away from his family home in Gujar Khan, now Pakistan, to volunteer for the British Indian Army, against his parents’ wishes. It was 1941 and his older brother Corporal Fazal Hussain was being held as a prisoner of war by Japanese forces.

Two years of intense training in Lucknow and Ferozpur followed, during which Hussain specialised as a gunner and wireless communications officer. He was one of an estimated one million Muslims who served in the British Indian Army during the second world war, though their contributions have been largely unrecognised.

“People aren’t necessarily aware of what Muslims contributed in the first and second world wars,” says Hussain’s grandson Ejaz. “It’s a failure that this hasn’t been recognised enough.”

Over recent years a number of dedicated campaigns have sought to change that. In October, community leaders and politicians stated that the history of Black and Asian soldiers who fought in world wars should be taught in schools, arguing that raising awareness could help tackle racism and anti-Muslim prejudice. Their calls came after towns and cities across the UK were plagued by racist riots at the beginning of August, following the Southport stabbings.

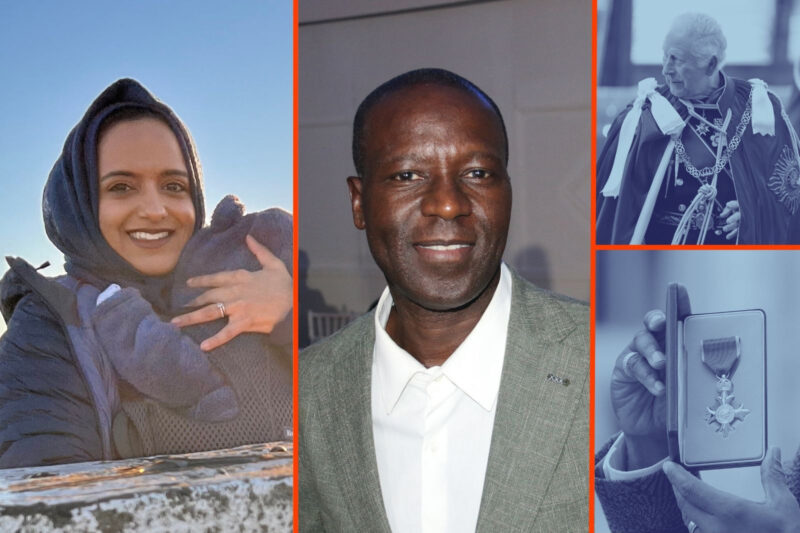

The efforts are being led by thinktank British Future, Leeds-based imam and chair of the Mosques and Imams National Advisory Board Qari Asim, Labour MP Calvin Bailey, and Baroness Sayeeda Warsi. In addition, 2024 marks the 110th anniversary of the first Muslim soldier — Sepoy Khudadad Khan — to be awarded the Victoria Cross for bravery.

“Most people now know that Indian soldiers fought for Britain in both world wars — but fewer are aware that many were Muslims from modern-day Pakistan. Only around a third of people know of the service of forces from Africa and the Caribbean,” says Sunder Katwala, director of British Future.

“The story of Khudadad Khan and others like him should be on the school curriculum. And commemorating all those who served, from all backgrounds, could make Remembrance Sunday a moment that brings people together across communities.”

Shrabani Basu, who led efforts to commemorate the British-Indian agent Noor Inayat Khan, the only Muslim woman to be awarded the George Cross, agrees that these stories should be taught in schools as an important part of British history.

“Their stories are inspirational, especially when we see that they fought in a war that was not of their own making, yet they fought bravely and made a difference. They played their role in the fight for democracy and liberty. It is important to remember that Britain would not have won the two world wars without the support of India and the colonies,” she says.

Hussain lives in Windsor and celebrated his 100th birthday in May this year. During the second world war, he was enlisted in the 8th British Army and served in the Italian campaign.

Following the war, Hussain returned to the subcontinent and served in the Pakistan military. He was honourably discharged after he broke his neck in an accident while on duty in 1958. He moved to the UK two years later.

Ejaz, who lives with him in Windsor, said the willingness of his grandfather and others like him “to fight for the British Empire with loyalty, despite being colonised” is extremely significant.

“We don’t understand the extent of the sacrifices of our elder generation. There were kids that had never left their villages and, suddenly, they were flung into far corners of Europe and they were there as volunteers,” Ejaz says.

“The riots we saw in August this year are an anathema, a complete contradiction to what my grandfather and others in the British Indian army fought for. They had divisions in terms of religion — there were Sikhs, Muslims, Hindus. But, when you unify people for one objective, all those differences dissipate, and they become united in achieving a common objective. I think this message needs to be given to this generation today.”

In March, then chancellor Jeremy Hunt announced £1m funding toward a war memorial for Muslims who died while serving in the world wars. The 13.2-metre minaret-shaped structure is set to be built at the National Memorial Arboretum in Staffordshire. Made of brick and terracotta, it will be inscribed with various stories of Muslim soldiers who sacrificed their lives for the country.

Philippa Rawlinson, director of the National Memorial Arboretum, said the funding for the memorial is an important step in “ensuring that the service of Muslim armed forces personnel is remembered in perpetuity”.

“Remembrance has been a vital human need for millennia, with constantly evolving practices paying tribute to public service helping to unite communities. We look forward to this fitting tribute to the service and sacrifice of Muslim service personnel being installed and dedicated in the future.”

Newsletter

Newsletter