Shoulders, knees and toes: the two retirees helping women break language barriers to healthcare

How do you express pain in your second language? Friends from Nottingham set out to improve health outcomes by teaching English medical vocabulary

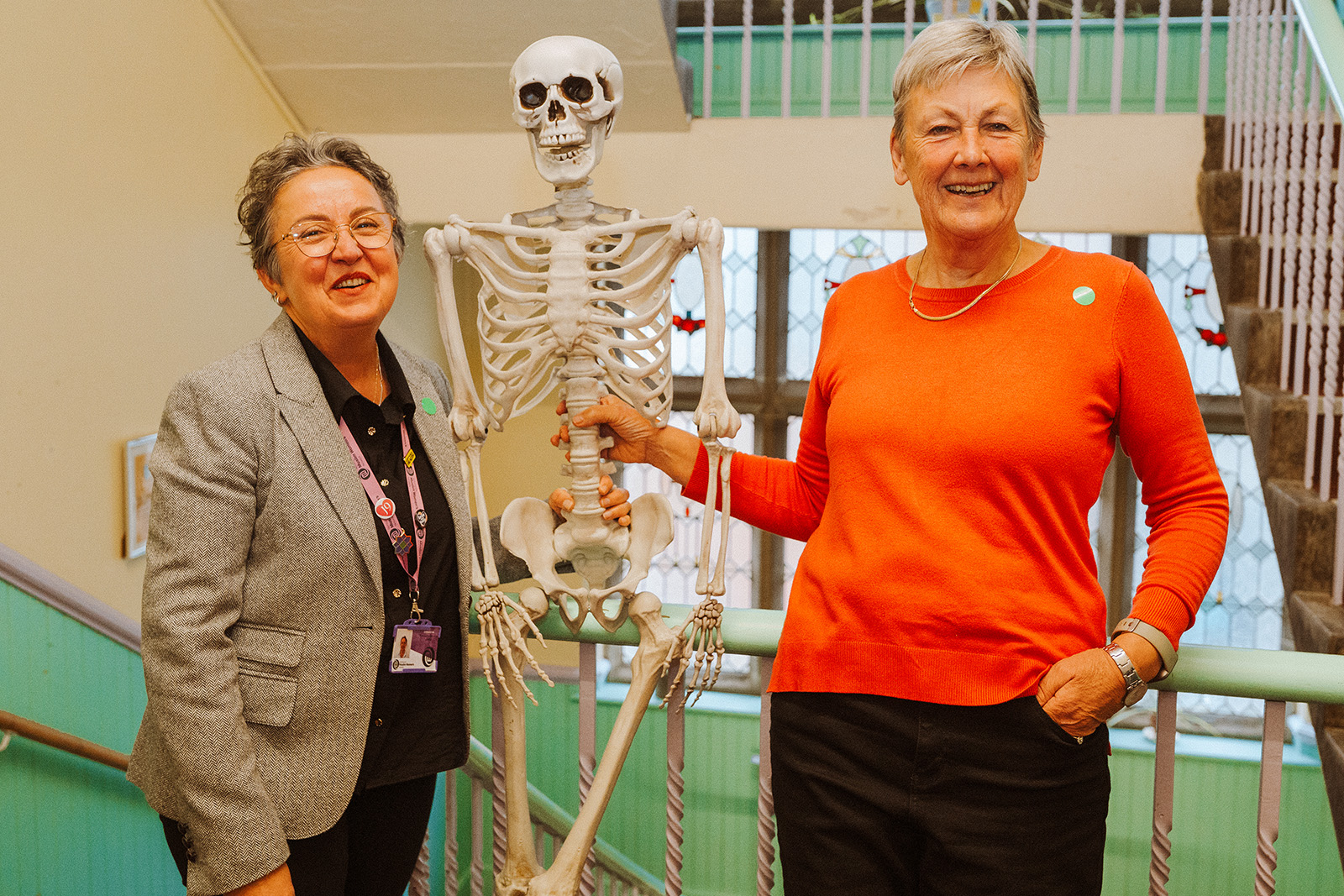

On a cloudy Tuesday in October, retired primary school teacher Jane Bowden boarded one of Nottingham’s trams with a life-size plastic skeleton folded over her arm.

Bowden was not, as many might have assumed, on her way to a Halloween party, but to teach a class of migrant women the very specific set of English vocabulary needed to navigate a healthcare setting.

She had been on a hunt for a skeleton model for months, but it wasn’t until October that she could find something affordable. The skeleton, Bowden jokes, is now the only male allowed into the Nottingham Women’s Centre, where every Tuesday she delivers medical English for speakers of other languages (ESOL) classes.

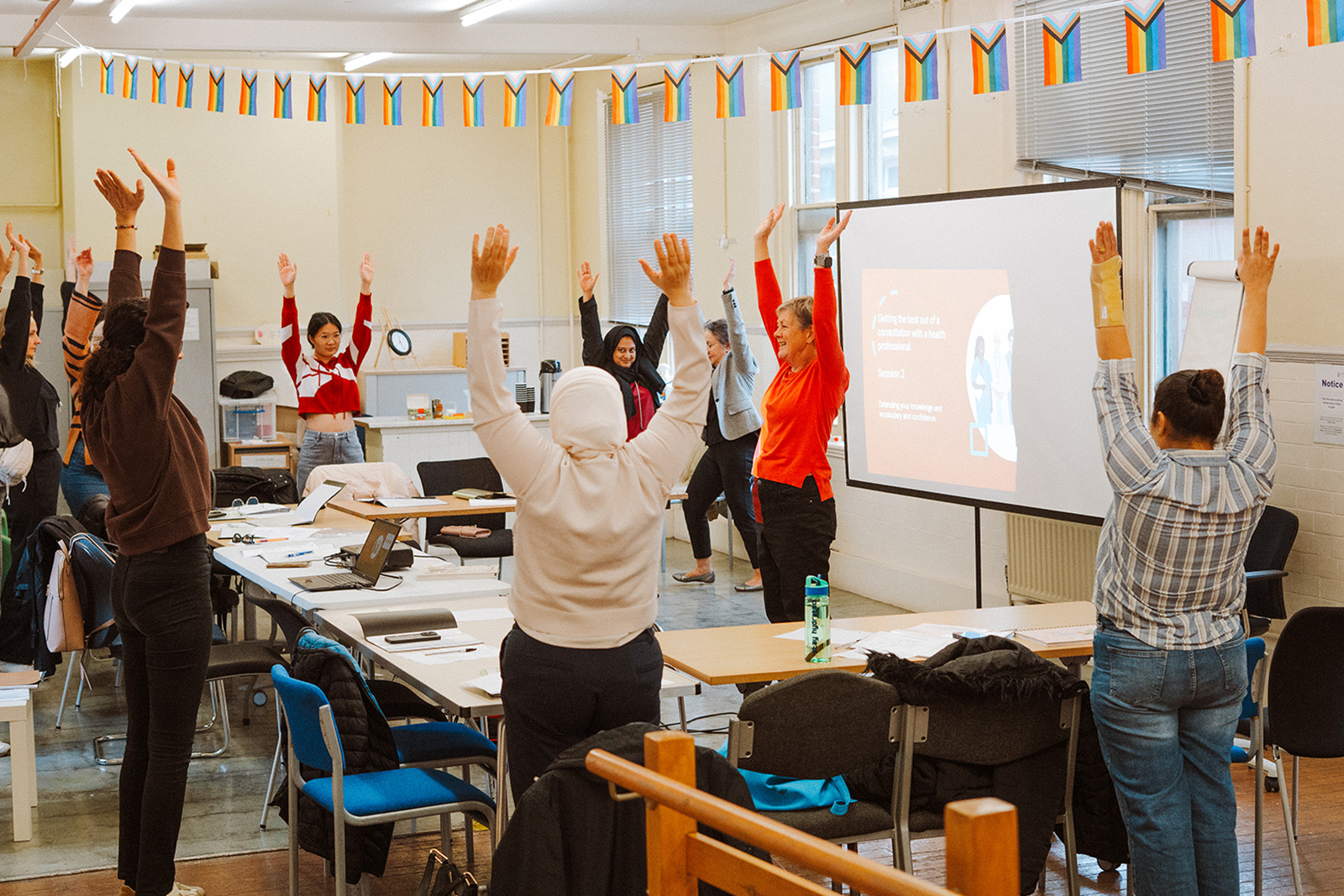

“I wanted the classes to be as interactive as possible,” Bowden says. “I know that with traditional ESOL classes there is a lot of writing and reading, but I wanted my course to be about talking and building a vocabulary.”

A group of 12 women — some in their 20s, others middle aged — sit on plastic stools in the classroom, the walls decorated with linoprints and paintings from other community workshops. Together they speak more than 10 languages, including Turkish, Ukrainian, Arabic, Cantonese, Punjabi and Pashto.

They begin by singing Heads, Shoulders, Knees and Toes to practice the body parts. Some share their own verses they’d prepared for homework, naming cheeks, chin, chest and hips.

“It can be hard to explain things to the doctor even in your own language,” says Marharyta Molokova, one of the participants from Ukraine. During the course, she’s learnt specific terms for body parts and ailments that don’t get covered in a conventional ESOL course. She recently learnt the word “shin”, handily illustrated by Bowden’s skeleton.

This is the third set of classes to be delivered since the course was launched by the Nottingham Muslim Women’s Network in April. It is designed to equip women who do not speak English as their first language with the vocabulary and understanding needed to independently schedule and attend doctor appointments.

“Sometimes when I go to the doctor I can’t tell them what’s wrong,” says another attendee, Anum Usman, from Pakistan. “But now that I have been to some classes I feel more confident.”

The classes are a collaboration between Bowden and Ferda Ozcan of Nottingham Muslim Women’s Network, born of an idea Ozcan had through her work within the Turkish community.

In one focus group, carried out by the network to better gauge the needs of Turkish women, many brought up the barriers to health care. “One woman said that her level of English was fine but that she said that she was having difficulties when she visits the GP because she doesn’t know the medical terms. She always asks for her husband or children to come with her,” says Ozcan. “I talked to more women and everyone was saying the same thing: that they struggle to communicate with their health practitioners.”

Language barriers are reported as one of the driving factors behind poor health outcomes for ethnic minority patients. According to a 2015 ONS report, people who could not speak English well were twice as likely to be in poor health than those proficient in the language.

Although the 2010 Equality Act and the General Medical Council oblige the NHS to provide language and translation services when necessary, years of cuts to both the NHS and the availability of ESOL classes in general have made language a significant barrier to primary healthcare access.

Ozcan says that she herself found doctor’s appointments a challenge when she first moved to the UK from Turkey, despite having a high level of English.

“My English was good but it was business English — speaking to a doctor is different,” says Ozcan, who is now retired and used to work as a marketing specialist. “Things like pain are especially difficult to express. You have to say what type of pain, is it sharp or dull, tender or sore?”

Ozcan had a strong vision for what she wanted to achieve from the beginning when she conceived of the course a year ago, but she struggled to find resources for her project.

“And at the beginning, we had nothing. We didn’t have any funds or contacts,” Ozcan says. Although she reached out to several healthcare professionals, she did not hear back from anyone willing to develop or facilitate the course.

That changed when she was introduced to Bowden via a mutual friend.

“I was retired, I thought I would just share some pointers and suggestions,” says Bowden, but she left the meeting having agreed to design the course. “Ferda can be very persuasive,” Bowden laughs.

Over the next months the two women worked together to develop the course from scratch, creating an six-week programme. As well as vocabulary, the course aims to equip people with the knowledge of their bodies and the NHS system. This includes information about services available at the pharmacy or through the NHS 111 phone service, which the majority of those taking part in the class had not heard about.

“We talk about things like health screening, how to schedule it, what happens when you attend one,” Bowden says. “If we are serious about screenings and we want people to attend them, then we have to take away their fear and lack of knowledge.”

One attendee, who did not want to share her name, said the classes helped her to find her bearings within the NHS as she moved to the UK only a few months ago from China with her husband.

“My husband has anxiety and depression so I have had to take the responsibility for organising the doctor appointments and helping him,” she says. “The class is very useful, but I wish more people knew about it.”

Ozcan would like to see the course develop and be adopted by different cities. This set of classes is supported by the Nottingham Muslim Women’s Network, but Ozcan is actively seeking more funding. “I don’t want to end here, I want to reach as many women as possible. My dream is for this to be something regular, offered to everyone in the UK,” she says.

Meanwhile, Bowden would like to find a life-size anatomical model of the human body to use in her classes, but the cost of models — even second hand ones — run into hundreds of pounds. For now, the B&M halloween skeleton will have to do.

Newsletter

Newsletter