Tory MPs are split: is the party too close to Reform?

Conservatives under Kemi Badenoch’s leadership are itchy as a modest conference and disastrous polling highlight just how far the party has fallen

I remember a conversation I had in the final, faltering days of the Conservatives’ time in office in 2024. I was speaking to a Tory MP who, until then, had only ever known political life in a governing party. “It might do us some good being in opposition,” they told me. There was a weary honesty in their tone, an acknowledgement that the party had lost its way and that some time in the political wilderness might be cleansing.

I put those exact words to a Labour MP, one who’d been elected back in 2005 but had spent 14 years in opposition. They laughed. “I don’t think they realise how irrelevant you can be in opposition,” they said. “It can be so hard and frustrating.”

That two-part exchange has stayed with me — and the Tory conference in Manchester this year has proved just how prophetic it was.

Being in opposition is always tough. Your policies carry less weight, your influence wanes and your fight for airtime becomes a daily grind. But for the Conservatives, a party so used to the trappings of power, the adjustment has been particularly brutal. Rows of empty seats in a modestly sized hall told their own story: a party once used to dominating British politics now looks a shadow of its former self.

It’s taken a year for reality to properly sink in. Last year’s leadership contest distracted from the deeper question of what the party actually stands for. Kemi Badenoch’s approach, a cautious refusal to announce much in the way of policy, left little impression on the public. The recent flurry of policy announcements at the conference was meant to mark a turning point but has barely registered. Cutting £50bn in government spending through benefit cuts, scrapping business rates in England and pledging help for first-time buyers were supposed to be the headlines. Instead, the focus fell elsewhere: on Robert Jenrick.

Jenrick, who lost the leadership race to Badenoch, has dominated news coverage of the conference after the Guardian published a leaked recording of him describing a visit to the Birmingham neighbourhood of Handsworth where he says he “didn’t see another white face”, adding that it was “as close as I’ve come to a slum in this country”.

He has since defended the remarks, insisting he was “pointing out a fact” about integration, rather than race. But, to be clear, he did, quite literally, point out skin colour. His defence raises uncomfortable questions: does the colour of someone’s skin determine how integrated they are into society? Would a white immigrant be automatically considered part of the fabric of Britain? And would Jenrick have made the same remark had he walked through a predominantly white town and not seen any brown or black faces?

I’ve spent time in Birmingham over the years, covering a range of stories for ITV News. It’s a genuine melting pot of cultures and faiths. I’ve filmed in mosques and churches, spoken to volunteers at food banks and met families from every background imaginable. Handsworth, where Jenrick’s comments were centred, is indeed largely made up of communities from ethnic minority backgrounds — around 91%, according to the city council — but it’s diverse within that. Roughly 23% are Indian, 16% Black African or Caribbean, 10% Bangladeshi, 25% Pakistani. That diversity is what makes the area, and the city, what it is.

Privately, many Tory MPs I’ve spoken to don’t think Jenrick said much wrong. Even Badenoch, who is repeatedly dealing with rumours that Jenrick wants her job, defended him, saying he made a “factual statement”.

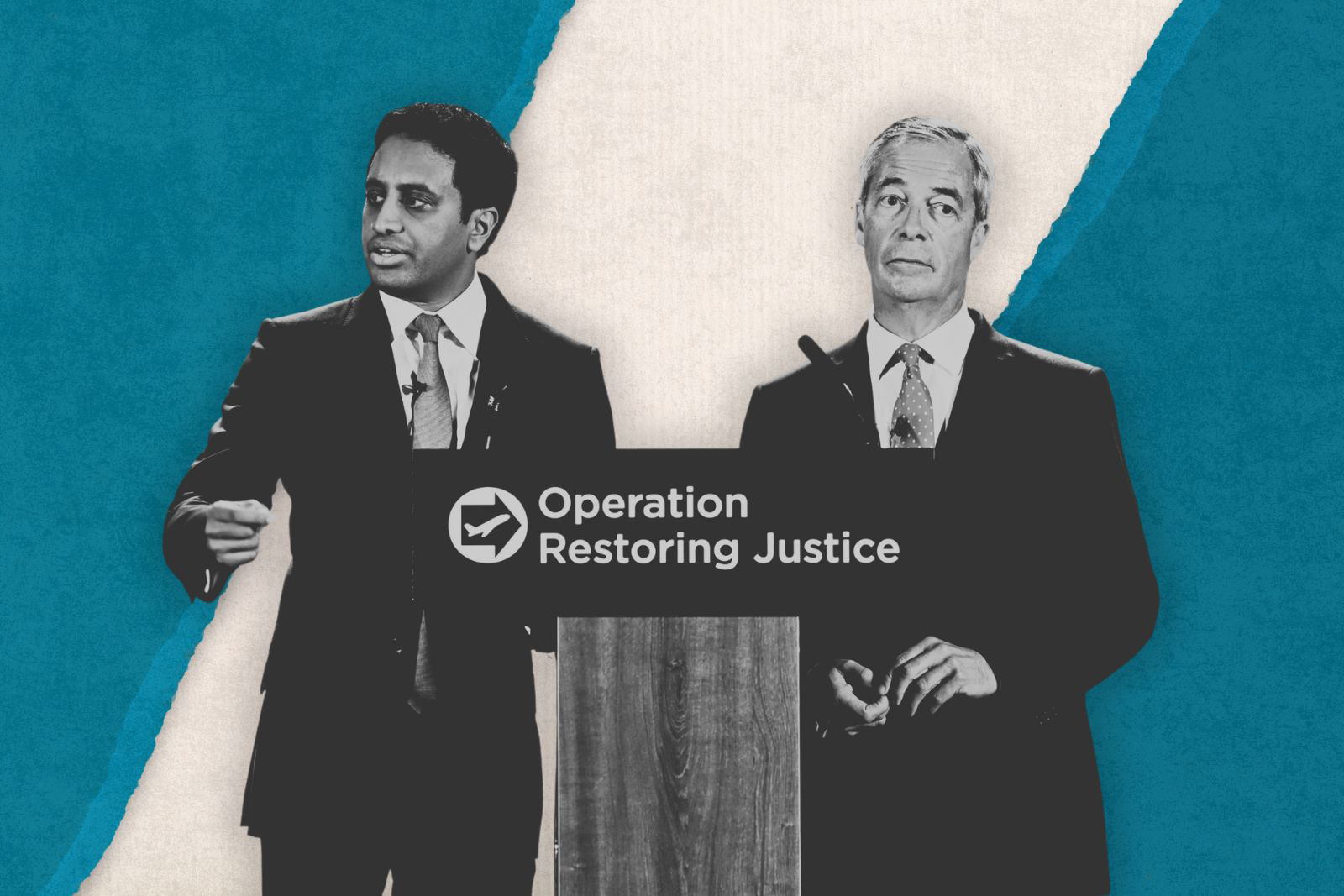

The discourse echoes what I’ve heard when I’ve attended Reform UK rallies — that parts of Britain are becoming “exclusively non-white”. It’s a talking point that now seems to have found a home within the Conservative party itself.

Not everyone, though, is comfortable with that direction. Some Tory MPs worry that the party is edging too close to Reform. “I fear for the direction we’re heading,” one told me, referring to the party’s drift to the right. Shadow chancellor Mel Stride has publicly distanced himself from Jenrick’s comments, calling them “not words that I would have used”. This is Westminster code, a quiet but deliberate rebuke.

Meanwhile, Reform UK’s support continues to surge. The party is now comfortably ahead of the Conservatives in polling, regularly welcoming Tory defectors. A growing number of Tory MPs are quietly entertaining the idea of a deal with Reform. One who had their majority slashed at the last election told me they thought that “a deal with Nigel Farage might be the only way to save the party”. They believe that, at current polling rates, Labour, Reform, and even the Liberal Democrats could all outperform the Conservatives at the next election — leaving them in a humiliating fourth place, which would be unprecedented for the party.

But when I’ve asked senior figures in Reform about the idea of an electoral pact, they have quite literally laughed it off. Their view is simple: they’re on the up, the Tories are in decline. As one senior Reform source put it to me: “Why would we do a deal to save them?”

For Badenoch, time is already running short. The next election may not be imminent, but the clock is ticking. Jenrick has been accused of being in campaign mode from the moment he lost the Tory leadership race and some within the party believe he would do better at taking on Reform than she has. If the party continues on its current trajectory, Tory MPs will get even more itchy. In other words, both major party leaders — Keir Starmer for Labour and Badenoch for the Tories — find themselves having their authority questioned by some of their MPs because of Reform’s popularity.

Shehab Khan is an award-winning presenter and political correspondent for ITV News.

Newsletter

Newsletter