Lyrical jokes and creative insults: inside the world of Arabic dubbing

The people behind our favourite characters — Bluey to Captain Majid — rarely appear on screen, but you’ll recognise their voices. They are the invisible actors shaping childhoods, identities and language skills

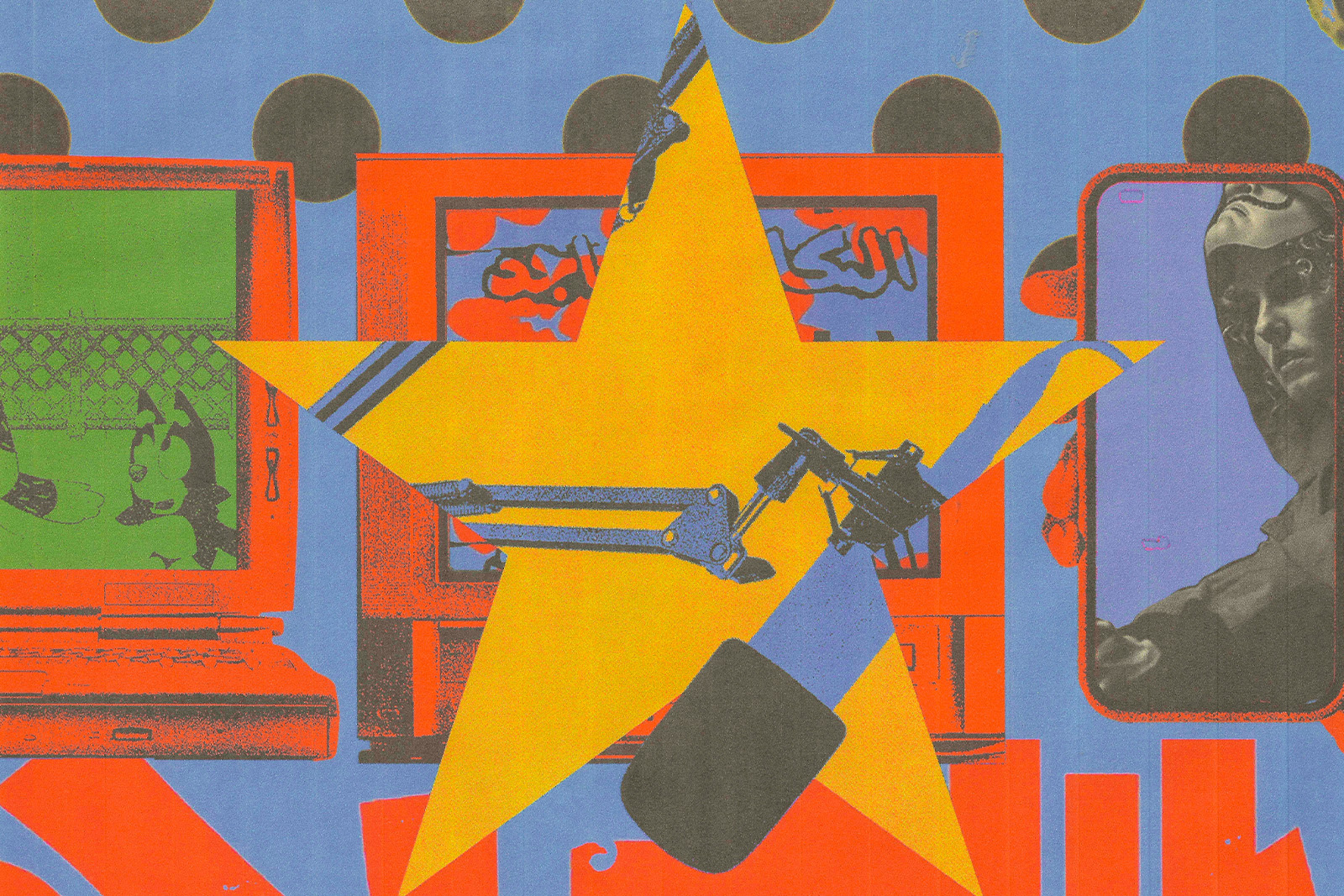

On a quiet afternoon, a child curls up in front of the television. Bluey bounces across the screen, but instead of English peppered with Australian slang, the dog family speaks in Arabic. The theme tune is sung with the same lilting rhythm, but with different words. For millions of children across the world, this is how they meet their favourite characters that will stay in their memories for much of their life.

For my generation, the show was Captain Majid (Captain Tsubasa), the Japanese football anime whose Arabic dub became a regional phenomenon on channels such as Spacetoon. For others, it was Disney classics such as Aladdin, but with more culturally fitting Arabic lyrics.

The people behind those characters rarely appear on screen, but you might just recognise their voices. They are the invisible actors shaping childhoods, identities and even language skills.

For Tracy Rahi, a Lebanese-British actor who works across stage and film, voice acting was a path she hadn’t imagined when she first trained at drama school in London. “They went through all the options to survive as artists,” she recalls. “One option I didn’t know was available was the voice acting industry.”

Rahi has lent her voice to productions including Layla (Netflix) and The Vigil 2 (BBC2). Dubbing is a fine art, she says. Rahi admits she watches dubbed versions of live-action dramas only when the commitment to voice performances matches what is on screen — which doesn’t always happen. Voice actors record separately and cannot react to their audio co-stars. “You lose a lot of the chemistry,” says Rahi. “For me, the process that works best is to stay true to how the original actor did it.”

That connection to the original actor is a strange one, she says. Rahi has never met a person whom she’s dubbed despite having this “intimate connection and intense focus on them when you are responsible for literally being their voice”.

She loves dubbing cartoons, which is more creatively fulfilling. “It feels a bit more like your own original work,” she says.

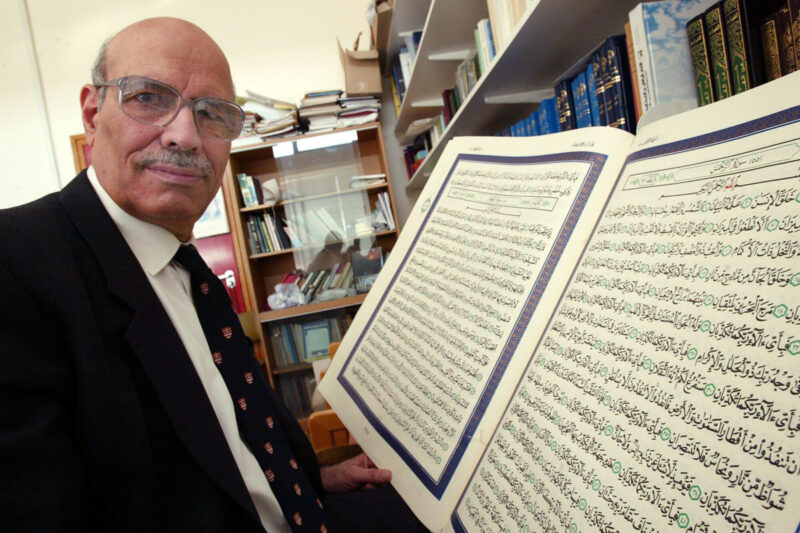

Voice acting in Arabic, Rahi explains, is not a monolith. She speaks three dialects. “Sometimes they’ll ask for something very specific, like Egyptian. Sometimes more general. And then there’s classical Arabic — that’s by far the hardest, even for me as a native speaker.” Yet that difficulty is also part of the magic: children across the region absorb modern standard Arabic through dubbed shows. “Even if you wanted to resist, you ended up learning it because of cartoons,” she says.

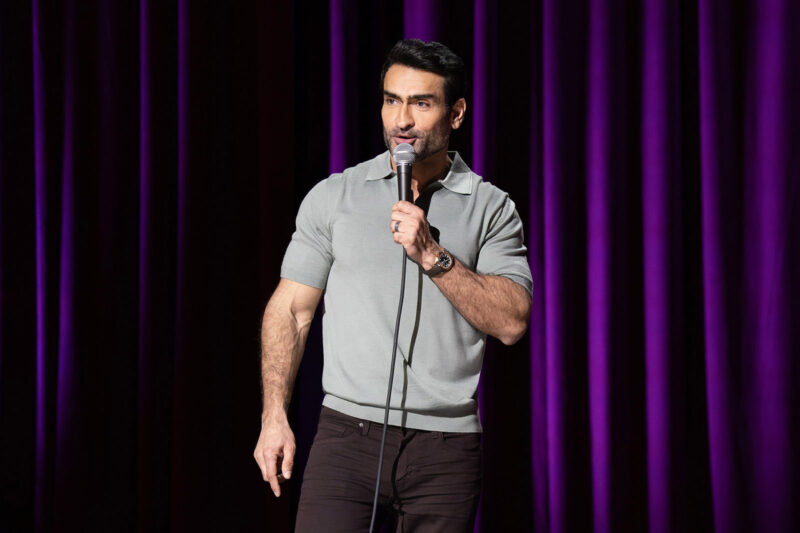

John Harley, founder and CEO of Adrenaline Studios, oversees dubbing in 17 languages. The former voiceover artist founded his company 15 years ago and has seen it grow at an astonishing rate, with dozens of employees and three offices in London, Hampshire and South Africa. While many other areas of the film industry have struggled, dubbing is booming, with studies projecting it to more than double in size over the next decade. Harley says that is largely thanks to the rise in streaming.

“Before 2015 it was mostly terrestrial broadcasters. Then Netflix came along and said: we’re going to dub everything. And the others followed,” he says. In addition, people’s viewing habits have changed; many of us often multitask while watching TV, making subtitles impossible to follow. And our screens themselves have shrunk, with people watching entire series on their smartphone.

But it’s not just scale; it’s also craft. “The longest part of the process is adaptation,” Harley explains. The tension between fidelity and adaptation is at the heart of dubbing. “We’re adapting culturally to where it’s going to be shown, and then adapting it for lip sync. That means replaying the same scene over and over, watching the mouth movements, changing sentences around to still sound natural.”

For culturally specific shows, that can be a minefield. “French or German often adapt better to English,” Harley says, “but something like Mandarin takes huge creativity. You might need a long sentence in English where Mandarin uses three syllables.” Sometimes actors from the original production even insist on doing the dub themselves in another language they speak, such as the Pixar film Coco, in which many of the cast, including Gael Garcia Bernal, Sofia Espinosa and Alfonso Arau, recorded both the English and Spanish language versions.

Australian slang in Bluey, the football commentary of Captain Majid or Spanish banter in Money Heist can be nearly impossible to translate word for word. Sometimes, the best solution is substitution — za’atar bread instead of Vegemite sandwiches — or a more expressive phrasing in Arabic. But it can be argued that some properties have been overly transposed, erasing too much cultural specificity from its origin. Obada Kassoumah, a Syrian who learned Japanese while studying there on a year abroad, decided to take on the task of translating the Captain Tsubasa comic for Arab audiences in an effort to retain the global appeal of the story without losing its origin.

Representation is the key behind dubbing. Harley describes how his studio casts sensitively. “We benefit greatly from casting actors whose lived experience matches the character — even if it’s a cartoon dog.” For one series, they cast a 12-year-old who uses a wheelchair to voice a character who also uses a wheelchair. “You don’t hear the wheelchair, but you do, you hear the experience in the performance.”

“That’s what voice acting is all about,” says voice actor Mo Heet. “I want my speech to be alive. Not boring. Fun, expressive.”

Dubbing often defines how a show is remembered. Captain Majid’s Arabic version, for instance, became a beloved Arab story of teamwork and dreams, and half the students in my primary school in Sudan had his face on their backpacks and pencil cases. I can still hum its theme tune, and it became a gateway into the world of anime and Studio Ghibli, an obsession I’ve since passed on to my children.

“I still watch cartoons in Arabic. When I watch in English now I think, ‘That doesn’t sound right’,” says Heet. “Egyptian is the most wanted. Next to it Lebanese or Syrian. Then Saudi. If you grew up on Cartoon Network in the Middle East, most of what you watched was dubbed in Egyptian.”

For some, hearing an Arabic-speaking superhero or a familiar dialect in a global franchise affirms that they, too, belong in these imagined worlds. For others, the sheer expressiveness of Arabic — the exuberant greetings, the lyrical jokes, the gloriously creative insults — shapes the shows into something uniquely theirs. As Heet frames it: “We are naturally very expressive. That’s what voice acting is all about. Why not make it bigger? Take advantage of Arabic’s strengths.”

As AI encroaches, the industry may change again. Synthetic voices can already generate cheap dubbing for YouTube videos. But as Harley insists, they presently pose only a minor threat, and audiences can immediately hear the difference: “Horrible things. You can’t monetise them online anyway. Real performance still matters.”

It’s in that performance — in the pauses, the breaths, the comic timing — that dubbed shows become more than translations. They bind people to language and to one another. In my case, they allow my children to stay connected to their Arab heritage despite living in the UK.

Newsletter

Newsletter