Governments don’t defeat racism. Ordinary people do

Solidarity and vigilance are the best defences against a rising tide of far-right attacks against Muslims and minority groups

The UK is facing a surge in racist violence. On Saturday night, the Peacehaven Mosque in East Sussex was set ablaze in a shocking attack. Speaking to Hyphen, the mosque’s manager described a rise in Islamophobic abuse over the past six months: hijab-wearing mothers harassed as they dropped off their children, Brown and Black pupils bullied in nearby schools and the mosque itself pelted with eggs.

The same night as the arson in Peacehaven, a mosque in Watford was vandalised with St George crosses. Reports also came in from Liverpool of a woman armed with scissors attempting to attack a group of young Muslim girls as they walked home from classes at the Abdullah Quilliam Mosque.

One day earlier, a 29-year-old man was jailed for wielding a knife during an attack on worshippers at the Jami Mosque in Portsmouth. He punched a man, kicked a prayer mat and shouted racist abuse before returning with a blade. In East Renfrewshire, Scotland, another man was arrested and charged in connection with smashing of a mosque window while children prayed inside. That incident came just weeks after a schoolgirl was assaulted nearby.

Last month, a nine-year-old girl in Bristol was shot three times with an airgun in what police have described as a racially aggravated attack. Over the summer, racist graffiti has been daubed on mosque walls across the country. As I have written for Hyphen, it is often smaller Black and Asian communities like these that find themselves at the sharp end of such crimes.

That’s why, this summer, I set up an independent monitoring and support service named Radar — Reporting and Documenting Acts of Racism. Our goal is to produce regular detailed reports mapping where racist attacks have risen, how the media has covered them and whether authorities have taken meaningful action.

The horrific attack on a synagogue in Manchester last week rightly drew condemnation from across the political and social spectrum. Carried out on Yom Kippur, the holiest day in the Jewish calendar, the incident left many in the Jewish community shaken and afraid. No one should ever have to fear for their life while gathered in prayer.

But instead of uniting against hatred, too many in our political and media classes chose to exploit the tragedy. They weaponised the attack, using it to stoke Islamophobia and undermine peaceful demonstrations in support of Palestinians.

The Daily Mail roared “HE WAS AN ISLAMIC TERRORIST” across its front page, as if the stabbing of innocent Jewish worshippers was somehow representative of the faith of 1.9 billion people. A GB News commentator went further, describing Islam as “a desert-dwelling seventh-century ideology”.

These are not isolated outbursts. They form part of a broader pattern — a narrative that long predates the Manchester attack and has created the conditions in which Islamophobia thrives. Such hatred does not exist in a vacuum. It is fuelled and legitimised by rhetoric from the top.

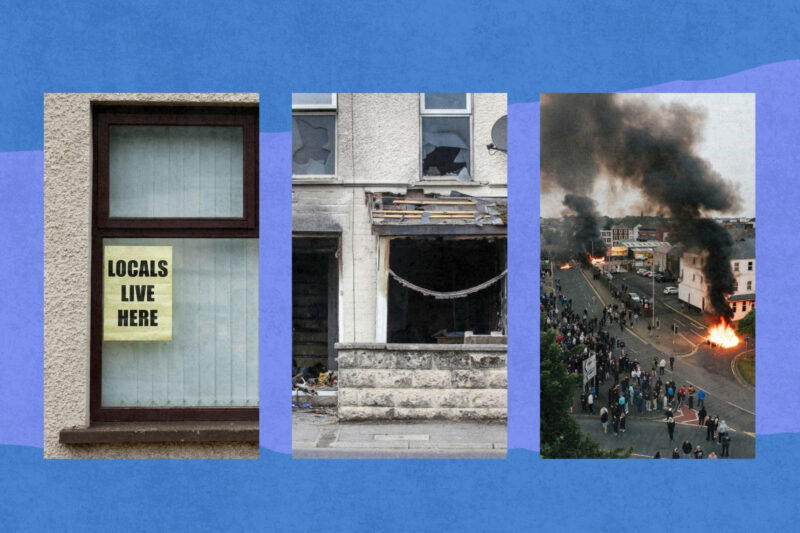

We saw this in summer 2024. While false information about the identity of the Southport attacker circulated online is widely attributed as the catalyst for the racist riots that swept across the country, statements by prominent political figures can also be seen to have inflamed the situation.

I recall one particular message that I received at that time. It came from a terrified Muslim man in the north-east of the country after days of violence in Hartlepool, Middlesbrough and Sunderland.

“We’re on the outskirts of Bishop Auckland and had to lock the shop up. My wife’s having panic attacks, terribly upset at the very real threat of violence and property damage,” he wrote. “My wife is making non-stop duas for our safety and all the Muslims. Just gonna batten down the hatches and pray it’s OK, inshallah.”

I barely slept during the riots. My phone buzzed constantly with WhatsApp messages, Instagram DMs and Twitter alerts, each reporting a new attack. For smaller, vulnerable Black and Asian communities, the fear was overwhelming — and justified.

In Middlesbrough, a group of white men set up a makeshift checkpoint, halting traffic and interrogating drivers about their ethnicity, demanding to know if they were “white” or “English”. A local Muslim woman named Shazia told me that her phone became a panic hotline, flooded with calls from terrified Muslim women.

Even after the riots subsided, racist incidents continued. Few were reported. Fewer still made the news. Too often, such attacks are dismissed as “antisocial behaviour” rather than recognised as hate crimes. That is simply not good enough. It emboldens racists and prevents the British public from understanding the scale of the problem and the corrosive effects it has on our society.

Like many other people, I have lately found myself thinking of what can be learned from the past. In the 1970s and 80s, when racist violence scarred towns and cities across Britain, it was ordinary people, including those from minority groups, who organised, documented and fought back against it. I hope to see Radar’s work forming part of that proud tradition of grassroots anti-racist organising.

Our aim as an organisation is to record incidents, support victims and amplify the voices of smaller, more isolated Black and Asian communities. It’s a modest, volunteer-run effort, funded solely through our GoFundMe page at present and very much in the early stages of development. We hope to establish ourselves as a not-for-profit organisation very soon.

As a matter of principle, we refuse state funding, seeing our role as one of holding the state accountable, not depending on it. In recent weeks, we’ve begun conversations with trade unions such as the National Union of Rail, Maritime and Transport Workers and Fire Brigades’ Union about potential collaboration. Organisations including the Runnymede Trust and the Institute of Race Relations have also expressed interest in our work.

The recent rise in overt and often violent racism across the country must be a wake-up call — not only for politicians and journalists, but for minority communities, too. Strength in numbers in our larger cities must not be allowed to breed complacency. We need to remember that smaller communities need our solidarity and practical support in these volatile and polarised times.

The lesson from history is clear: there are no heroes in Westminster coming to save us. Racism will not be defeated from above. It will be defeated by us — ordinary citizens who refuse to look away.

Newsletter

Newsletter