Patriotism isn’t about flags — it’s caring enough to make this country better

Why should we let people who seek to divide us define our history and identity?

They’re hard to miss. The red crosses on walls, lampposts and roundabouts across our country. “This is England,” say supporters. “Why shouldn’t we be allowed to fly our own flag?”

Just over a week ago, the UK also witnessed its largest far-right demonstration in recent memory. An estimated 110,000 people travelled to Whitehall, central London, to take part in the Unite the Kingdom rally, organised by anti-Islam activist and founder of the English Defence League (EDL) Stephen Yaxley-Lennon — also known as Tommy Robinson.

The people hanging flags and marching consider themselves patriots and defenders of a British identity under existential threat. But what does that really mean and who, precisely, gets to define what it means to be both British and patriotic?

Very few people in the UK take issue with anyone raising flags in celebration of a sporting victory or any other moment of celebration. But, for many Black and Asian elders, those banners can have an altogether different meaning. They carry memories. Memories of being chased, spat at and beaten against a backdrop of red, white and blue.

“When we saw the Union Jack, we saw trouble. The violence was very common. You’d be wary. We heard the P word every other day. There were certain areas and estates that you wouldn’t go,” recalls my friend Shaz Zaman, who grew up in Luton in the 1980s — a time where there were certain roads in town you simply wouldn’t walk down as a Black or Asian person.

That history matters, especially when we look at who’s pushing the latest wave of flag-flying. The Raise the Colours campaign sounds harmless enough, but scratch the surface and the story changes. According to Hope Not Hate, the campaign has been led by Andrew Currien, a former member of the EDL who now provides security for the far-right political party Britain First.

While some supporters frame the project as a benign expression of national pride, critics say it has been closely tied to racist incidents.

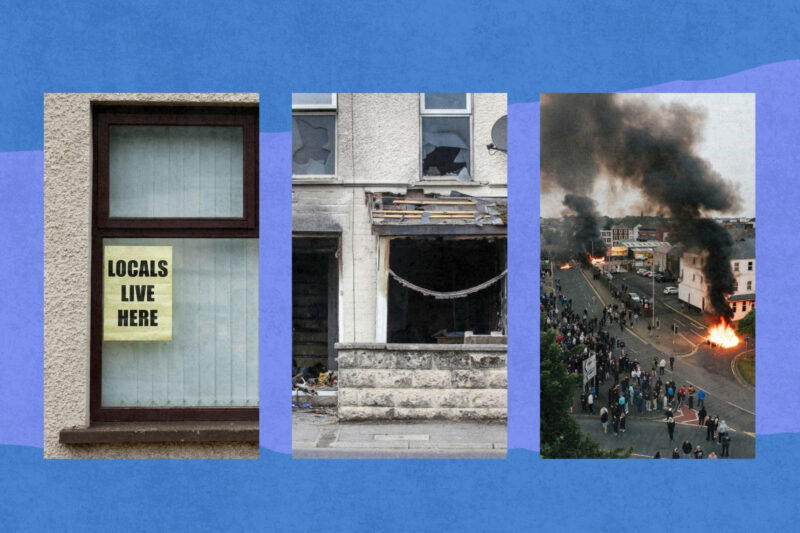

Last month, the South Essex Islamic Centre in Basildon was defaced with red crosses and daubed with the words “Christ is King” and “This is England”. In Portsmouth, a man allegedly shouted racist abuse at Muslim families outside a mosque, punching one man in the chest before pulling a knife. In Southampton, a mosque security guard told me about a woman who smashed the building’s CCTV cameras and threatened to kill worshippers.

Similar incidents have been reported elsewhere, with racist graffiti appearing in County Durham, Houghton-le-Spring, near Sunderland, and York.

So, no, I’m not offended by the St George cross. It’s the flag that I get behind when I’m cheering on our national football team. I am, however, deeply concerned about the racist ideologies — and the acts of violence and intimidation — that too often fly under its cover. There’s no conflict between those two positions, either. Celebrating the good things about our country should never prevent us from confronting the bad.

My idea of patriotism isn’t about flags, nor is it about nostalgia for a past that never really existed. It’s about caring enough for this country to want to make it better now.

It’s about clean streets and safe neighbourhoods. About helping your elderly neighbours with their shopping. About lifting a stranger’s suitcase up the train station stairs. About making sure that multinational corporations pay their fair share of tax to fund our NHS, schools and infrastructure. About taking back control of our water, rail, mail and electricity, so they serve the British public, not boardrooms and shareholders. About decent public services for everyone who needs them.

Yes, I despise the crimes of empire. No, I’m not a fan of monarchies or disastrous foreign wars. And, yes, for some people, the colour of my skin and the faith I follow will always be enough to disqualify me from being “truly” British. But why, when the truth is so very different, should we let people who seek to divide us define our national identity?

Britain has been shaped by migration for centuries. The earliest Black Britons lived under Roman rule. In the 13th century Italian bankers and German merchants set up shop in London. In the 17th century, Protestant Huguenots fleeing persecution in France brought textile and watchmaking skills that enriched local economies.

Irish workers powered the industrial revolution, building canals, railways and roads. After the second world war, migrants from the Caribbean, South Asia and Africa answered Britain’s call to rebuild a shattered nation, working in hospitals, factories, transport and other vital industries.

Britain’s story is also one of working-class people of all backgrounds fighting for and winning many of the freedoms we enjoy today. As the late historian EP Thompson highlighted throughout his work, our nation’s past is not one of kings, queens and generals. It’s the Levellers demanding political equality against the might of Cromwell’s army in the 17th century. It is the Diggers declaring the earth a “common treasury for all”. It’s the Chartists who filled the streets holding petitions demanding votes for ordinary men at a time when democracy was a little more than a dream.

It’s also the blood spilled at the Peterloo massacre in 1819, when tens of thousands gathered peacefully in Manchester to call for representation, only to be cut down by cavalry sabres. It’s the Durham miners, who for more than a century have marched behind brass bands and embroidered banners, celebrating their communities and asserting the dignity of working-class life. Many of the rights we now have came not from the benevolence of our rulers but from ordinary people getting together to demand their worth.

Black and Asian Britons have shaped working-class struggles too. From the Asian women who stood side by side with dockers, miners and postal workers at the Grunwick film processing factory in 1976 to demand better working conditions, to the Black and Asian communities in Yorkshire and the Midlands who fed miners’ families during the strike of 1984-85.

The Britain I know is grime music and chicken shops. It’s fish and chips after Friday prayers. It’s the beauty of the British countryside contrasting with the busy sprawl of our big cities. It’s a crowd of Scousers at Anfield erupting as Mo Salah drops into sujood after scoring a screamer. It’s Marcus Rashford forcing a government U-turn to feed hungry children. It’s a national team of Black and white players taking the knee, even as some boo from the stands. It’s a country of contrasts and contradictions. Rich and poor. Black and white. In some respects united, in others deeply divided.

It’s not perfect, but it’s ours. And no one should ever make us feel otherwise.

Newsletter

Newsletter