What happens after a restaurant goes viral?

With foodies now searching for more authentic culinary experiences, small, family-run halal eateries have found themselves dealing with sudden fame and long waiting lists

Tucked away at the back of Queensway Market in west London is Normah’s, a six-table Malaysian family cafe serving traditional dishes such as beef rendang and king prawn laksa. Founded in 2015 and run by Normah Abd Hamid and her nephew, it was once an under-the-radar favourite.

Then, just over a year ago, came Eating with Tod — an influencer with nearly a million followers on TikTok who is famous for rubbing his hands together before tucking into his food in a way that makes me never want to eat again.

Normah’s now has a two-month waiting list, with bookings opening at 10am on the first of every month in a process usually reserved for fine-dining establishments with Michelin stars. Despite repeated requests, no one at Normah’s was available for comment — perhaps wary of drawing any more media attention to their already overwhelmed two-person operation.

Once held more or less solely by critics, the power to popularise a restaurant has now moved to social media influencers. The more “niche” and “authentic” the experience is deemed to be the better. Content creators from Topjaw’s duo of Jesse Burgess and Will Warr to Lylaa Ali Shaikh — better known as saltandshaikh and named one of the top 10 foodies of Instagram by the Evening Standard — travel around cities sampling cuisines from around the world for an ever-growing audience.

While most small restaurant owners probably aren’t averse to attracting more customers, they are not always equipped to deal with sudden fame.

“If a reel hits the algorithm right, then there’s no upper limit to how many people watch it,” says Jonathan Nunn, food writer and founder of Vittles. “If you add the popularity of hidden gem content, then you have the perfect set of circumstances for small restaurants to achieve virality, albeit in ways they did not expect or prepare for.”

An early champion of Normah’s, Nunn tells me he has not been able to get a booking for the past year.

Lebo Lebanese Grill on New Kent Road is a local kebab shop that has found itself a destination restaurant following social media coverage. Amir Idreis opened the unassuming south-east London takeaway in 2008. While it quickly established a local reputation for fresh and affordable food served late — I was a regular when I lived around the corner in 2014 — the rise of platforms such as TikTok brought attention from further afield. Lines of people now snake down the road.

“We go viral weekly sometimes,” Idreis tells me. “Someone discovers us and posts it, everyone says, ‘Please don’t tell everyone about our spot’, and the cycle repeats.”

The team makes sure to always have enough of the most popular item — the half-chicken served with chips — ready on the grill, but online fame has led to a rash of imitation restaurants attempting to pass as franchises.

“All we can do is inform people that they’re not a part of us,” says Idreis. “Our message is: ‘We grill, they grill, but there’s only one Lebo’.”

Bake Street, a small neighbourhood cafe in Hackney with no indoor seating, is as famous for its “filet-o-fish” sandwiches and crème brûlée cookies as its semi-permanent queue out of the door.

Siblings Feroz and Amirah Gajia founded Bake Street in 2015 out of frustration at the lack of options and quality in the halal cafe market. They’ve since built a sizable Instagram following, which they use to announce their weekend specials and limited-run merch drops.

Feroz recalls the 50-person queues that would regularly form when they launched their Nashville hot chicken buns in 2021. “The initial shellshock of going viral and being incredibly busy shows you all the possible flaws in your business,” he says. “It also becomes a question of, ‘Does virality define you or will you define yourself?’”

They chose the latter option, focusing on maintaining a sustainable working environment geared towards long-term productivity rather than working themselves into the ground catering to short-term hype.

“For some places having a line is great marketing, but a line stresses us out. We don’t want to artificially create hype to the detriment of customers waiting to be served,” Feroz adds.

Bake Street remains halal and some of its most exciting offerings are versions of foods usually off limits to Muslims, including a “BLT” and sausage breakfast McMuffins. But Feroz reckons its clientele is now majority non-Muslim.

“Part of that is definitely the more informal nature of our offering and because we only have outside seating,” he says. “But Bake Street has always been a hub for the community. The Muslims who are excited and enticed by the interesting and different things we do still come to see us.”

Although Bake Street and Lebo Grill were open for years before trending online, restaurants can now find themselves going viral before they’ve even had a chance to settle in. BÔNE in east London, with a fixed halal menu and live music, only opened in February but is already fully booked until 2026.

Its eight-hour beef short rib accompanied by unlimited fries and impressive mocktail list — the restaurant does not serve alcohol — offer a novel dining experience for people who follow a halal diet and are usually excluded from such spaces.

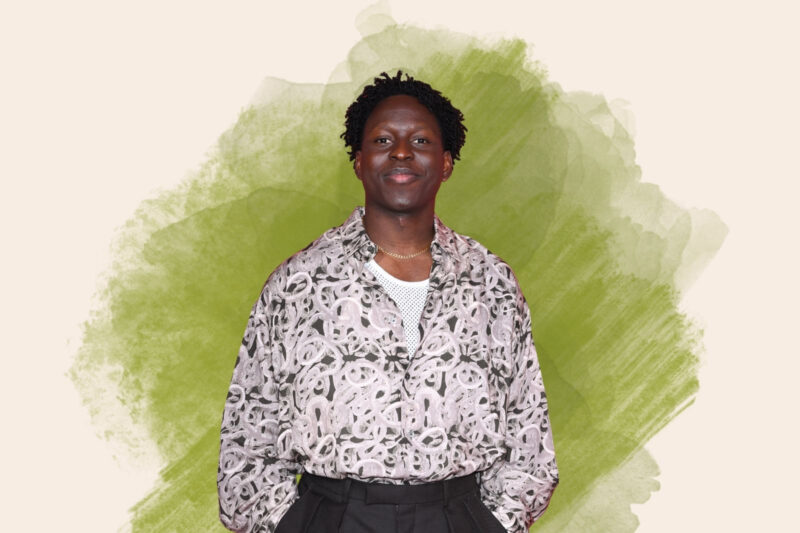

“You don’t really get much of an option, so we just wanted to be that option and basically target a whole demographic that’s being missed out,” says founder Abdinasir Sharif. “Maybe it’s selfish, but it’s all just things that I myself want in a restaurant. I think a lot of other people want that too.”

Shortly after launch, Sharif posted online about the concept behind BÔNE. That led to a surge in bookings, some of which were made by influencers with large followings. Before he knew it, he was booked up until next year.

Sharif was caught off guard by how quickly it happened. “It’s been a bit more hectic than I had hoped. How do people know what they’re doing a year in advance?” he laughs.

BÔNE’s original booking system immediately crumbled under the weight of incoming reservation requests and the restaurant has already had to move locations. Nonetheless, Sharif is keen to avoid the temptation to expand too quickly.

“Social media is doing a great job for a lot of businesses, but it’s also damaging them in that they go viral and have all these customers in a short amount of time — and then they just don’t return,” says Sharif. “By then you’ve lost your service, your food quality has gone down, you’re consumed by the hype and you’re not thinking about how sustainable this is.”

Back at Bake Street, Feroz agrees that social media popularity doesn’t always lead to longevity. “For me, it always needs to be a mix of regulars and people who travel to us to make the business work,” he says.

“Without our regulars we wouldn’t be able to have a team to execute everything we want to on weekends. It gives us the freedom to be creative without being worried about making viral things.”

Newsletter

Newsletter