Releasing suspects’ ethnicity is a gift to the far right, Labour MPs warn

Police will be able to release ethnicity and immigration status after charge in a move ministers say will quell misinformation. Others are wary

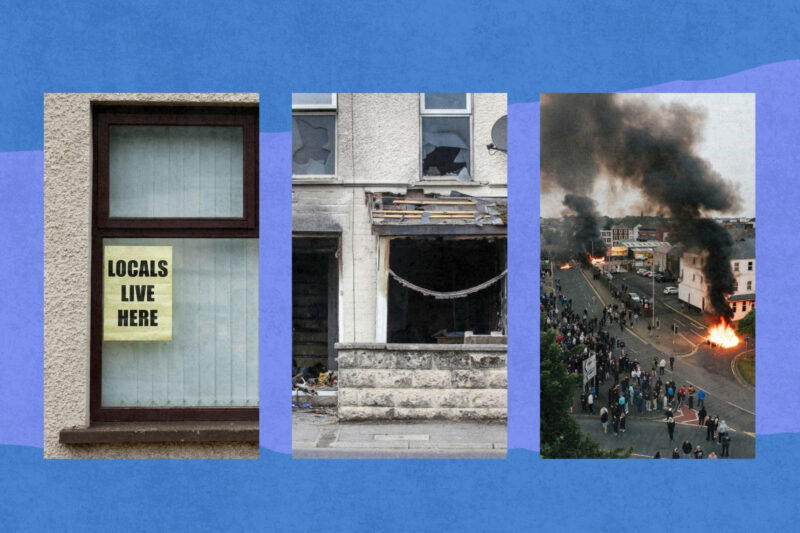

The tragic murders in Southport last year caused a sense of national trauma. Three young girls at a dance class were attacked and murdered while eight others were badly injured.

In the hours after the attack, grief collided with shock. Understandably, there was anger at the senselessness of the crime, the brutality and the lack of answers. People wanted to know who could do such a thing but, initially, police offered few details. The person charged with murder was not named because he was 17 at the time, in accordance with national guidance. In that vacuum of information, social media became the breeding ground for conspiracy theories.

The day after the incident, rioters targeted a mosque in Southport. Rumours online suggested the perpetrator was a Muslim asylum seeker being monitored by authorities. Over the following days, violence spread across the country, fuelled by the perception that police were hiding the truth.

Eventually, the facts emerged: the attacker, Axel Rudakubana, was British-born. Many now believe that much of the unrest could have been avoided if more details had been released sooner.

This question — when and how to disclose key details about suspects — has been a point of contention ever since. Now, the National Police Chiefs’ Council (NPCC) has announced new guidance whereby, in high-profile or sensitive investigations, police will be encouraged to disclose the ethnicity and nationality of suspects who have been charged.

The stated aim is to reduce public risk when misinformation is spreading, particularly in cases that grip national attention, and ensure trust and transparency is restored.

In some cases, it could be a way to undercut the dangerous rumour mill before it spins out of control. But a number of Labour backbenchers I spoke to pointed out what they believe is a glaring omission: in cases where the suspect is, in fact, from an ethnic minority background, confirmation of that could result in heightened tensions.

“I’m all for transparency in government,” said one. “But publishing suspects’ ethnicity in this climate? That’s like handing torches to a lynch mob and rebranding it as ‘better lighting’. It’s not policy — it’s a gift to the far right.”

Some legal experts I have spoken to also fear this is a kneejerk reaction to public outrage rather than a carefully measured reform. Lawyers warn that releasing information on immigration status in particular, which may not be relevant to a trial, could prejudice a case or influence potential jurors, jeopardising the fairness of the judicial process or even causing a prosecution to collapse. The courtroom is supposed to be a place for evidence, not public opinion shaped by early headlines.

It is a concern shared by government ministers, who have told me steps will be taken to ensure that this does not happen. They argue that, if there is a risk of this, police can and will decide not to publish the details.

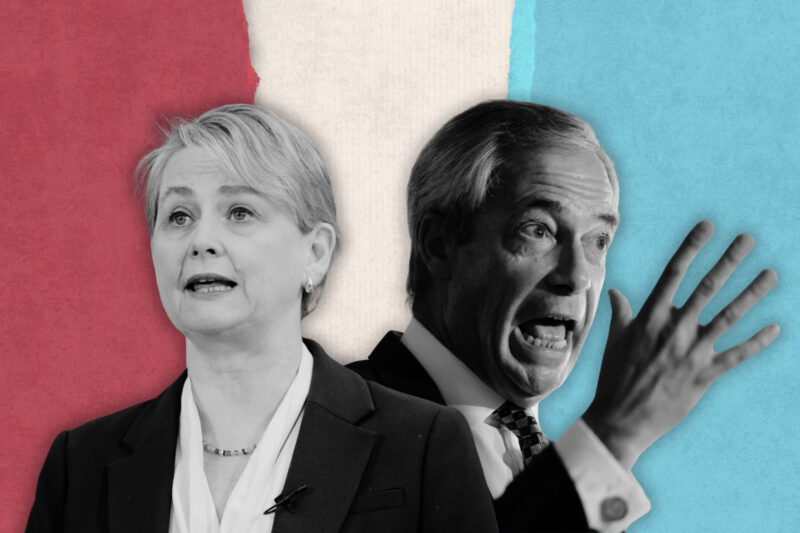

Others see a more political undercurrent. Labour’s support for the change, they argue, has been influenced by Reform UK — a party that has been pushing this issue hard. Nigel Farage has long criticised the police for withholding details about suspects; just last week, I attended a press conference for ITV News where Reform claimed Warwickshire police had concealed information about the alleged rape of a 12-year-old girl in Nuneaton. The immigration status of the two suspects is now public; police said they were simply following existing guidance in initially withholding it.

One Labour MP told me they believe their party has taken the bait. “This was manufactured hysteria and we have fallen for it,” they said. “What difference does the ethnicity make to a crime? A crime is a crime. We continue to move in the wrong direction.” Another MP called the change “toxic”.

I put the idea that this had all been motivated by Reform UK to policing minister Diana Johnson. “No,” she said. “This goes back to last year and what happened in Southport.” Work on the policy, she told me, had been ongoing for months. Yvette Cooper, the home secretary, has welcomed the change in guidance, describing it as a “step forward”, adding that she believed the public want “greater transparency”.

Not all Labour backbenchers are opposed to the scheme. In fact, some who are usually more critical of the party’s leadership support the change. “It will stop misinformation,” one told me. Another was adamant that Farage had nothing to do with it. “It stems from what happened with the Southport riots and then in Liverpool.”

That Liverpool incident came earlier this year, when a car ploughed into a crowd celebrating Liverpool FC’s Premier League victory. This time, Merseyside police moved quickly to clarify that the suspect was white and British. The swift disclosure helped quash online rumours that it was a terror-related incident and potentially helped prevent further unrest.

Those supportive of the new change are adamant this isn’t simply about the ethnicity or nationality of suspects. It’s about trust — or the lack of it. In Southport, the absence of detail created a vacuum, and in that space, falsehoods thrived. In Liverpool, rapid clarity arguably prevented the same outcome. The question is whether police forces can consistently judge when releasing such information will calm a situation rather than inflame it.

Former police officers that I have spoken to warn that this will be the challenge moving forward and getting the balance right will not be easy. Whichever side one takes, the Southport murders remain a grim reminder that how we communicate in the wake of tragedy can shape what comes next. Ultimately, how this guidance is used will have huge implications for policing — and society.

Shehab Khan is an award-winning presenter and political correspondent for ITV News.

Newsletter

Newsletter