‘A place of worship should not look like a fortress’

A year after rioters targeted the town’s only Muslim prayer space, worshippers are optimistic but wary of the threat from the far right

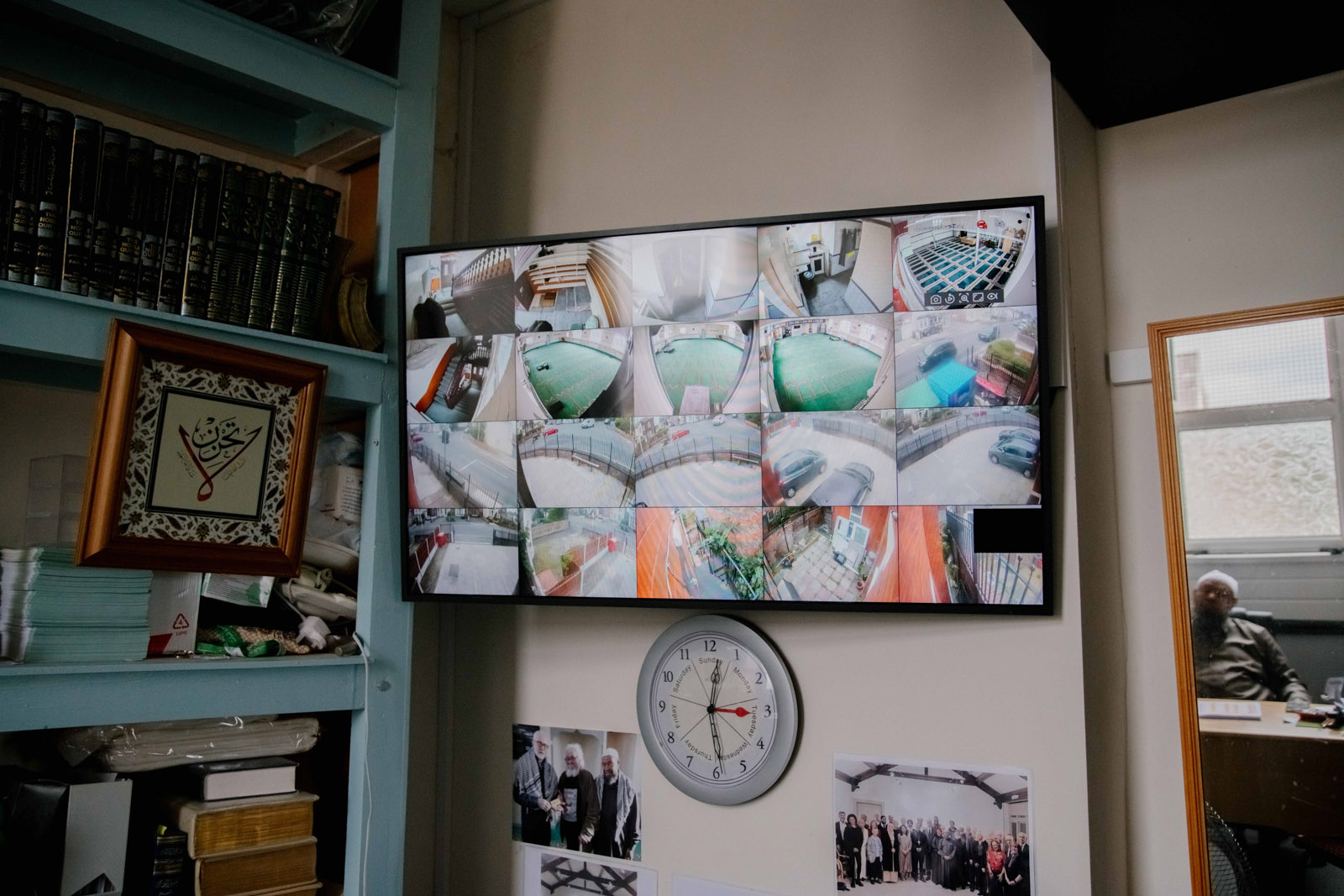

On a hot and humid Monday afternoon at the Southport Mosque and Cultural Centre, imam Ibrahim Hussein, chair of the town’s only Muslim place of worship, sipped a cup of coffee, pointed to two large CCTV monitors in his office and took stock of the past 12 months.

“We faced something that we have never faced before,” he said. “We’ve never seen something on this scale at home. So, to us, it was a shock and it was a wake-up call that we can’t just carry on assuming that things are all right. There are a lot of things brewing under the surface and we are not aware of them.”

Hussein, 68, was referring to two events in 2024 that shook both Muslims and non-Muslims in this otherwise sleepy Victorian seaside town and sparked the UK’s worst racially motivated rioting in decades. First, on 29 July, Axel Rudakubana, a troubled teenager obsessed with violence and killing, took a taxi to a Taylor Swift-themed dance class in Southport and, armed with a knife, rampaged through a crowded room, murdering three children and wounding eight others, along with two adults.

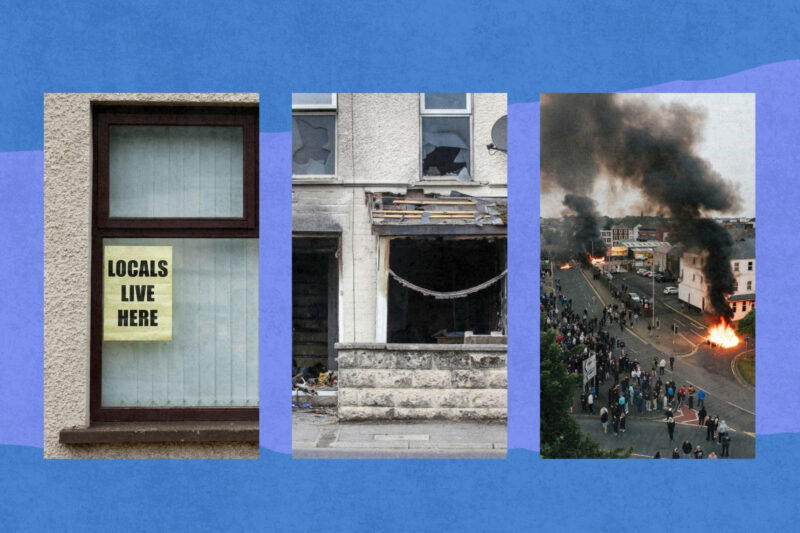

The town was reeling from the horror of the attack when, less than 24 hours later, a vigil to honour the children was hijacked by hundreds of people who flooded local streets in response to rapidly spreading online misinformation about the identity of the attacker. Convinced that the attacker was a Muslim immigrant, they threw bricks at the mosque, tore down a fence, set a police vehicle on fire, attacked police and looted a nearby shop.

As rioters chanted “No surrender!” and “English till I die!” more than 50 police officers were injured in the violence.

The ferocity of the rioting in Southport catalysed similar violence across nearly 30 towns and cities in England and Northern Ireland over the next week. As men, women and young people attacked libraries and hotel accommodation for asylum seekers, disturbances in cities including Manchester, Sunderland, Leeds and Blackpool underlined how the rapid dispersal of politically motivated disinformation on platforms such as X, Facebook and Telegram can have alarming real-world consequences for minority groups including Muslims and refugees and leave local officials, politicians and the police all but powerless to act.

“We have always considered ourselves part of the community,” said Hussein, a resident of Southport for nearly 20 years. “We suffer from what everyone else suffers from, like inflation or the doubling of gas prices, or education or transport matters. We are in the same boat. So, to be singled out as the cause of all that is false.”

On the evening of the violence, Hussein was in the mosque with other worshippers and two advisers from the Home Office. He watched, terrified, as attackers threw projectiles at the mosque and set fire to a police vehicle. A number of them attempted to force entry, but were held back by police.

“They came in here to spread hatred,” he said. “What they were doing was planning to come in here and burn the place down and kill anybody inside. Those who were inside the mosque are still not over the emotional shock.”

Hussein and the worshippers stayed inside until police had dispersed rioters around midnight. “I was terrified of the violence, which had been fuelled by false news. In my more than 50 years in Britain, I never encountered anything like the rioters who attacked the mosque.”

Struggling economy

Like other UK towns and cities rocked by rioting — Ballymena in Northern Ireland is one recent example — Southport will take years to recover from the events of 2024. Tourism, the town’s primary economy, was an immediate casualty with countries including Malaysia, Indonesia and India all issuing safety warnings to citizens about travelling to the UK. The town usually attracts around nine million visitors annually, who contribute more than £550m to the local economy.

The violence brought the local hospitality industry to a standstill as tourists cancelled hotel rooms and tour operators axed coach trips. Alfie Patel, a local business owner, said that his family has worked in Southport since 1996. Patel co-owns The King’s Plaice, a fish and chip restaurant on Lord Street, an area elegantly lined with shops, restaurants, bars and hotels, a short walk away from local beaches.

Patel was on his way to a local cash-and-carry when Rudakubana carried out his attack. He drove back to his restaurant and decided to close early that afternoon and the next day.

“We closed the shop at four in the afternoon to protect the staff and the shop,” he said. “We were fearing for our lives, there were messages going round, it was like a lynch mob. It was a very worrying time. I’ve never felt anything like it in my life, ever, in terms of fear and intimidation.”

Patel said the riots all but paralysed Southport’s tourist economy. “It happened at the wrong time because we are a seasonal town. We saw a 70% drop in footfall afterwards, the whole summer was gone. We’re only now beginning to get over it. Everyone suffered.”

He pointed to the town’s demographics — 25% of locals, also known as “Sandgrounders”, are 65 years old and over. “Tourists who come to Southport are elderly too. They’re not going to come if they see this place is on the news. The impact of the violence was very bad for businesses.”

A wary optimism

Members of Southport’s small Muslim community — estimated at only 300 people out of the town’s population of about 95,000 — are relieved there has been no repeat of last summer’s violence, but remain wary.

“I think the attacks have made people more cautious,” said Owais Patel, a local college student. “It’s just racism, really, and has no place anywhere.

“We have slowly moved on: our condolences go out to the parents of the girls because we could never know how that feels. They will always be in our hearts in Southport.”

I had a coffee with Neil Frackelton, the chief executive of Sefton Women’s and Children’s Aid, a domestic abuse charity. He told me he was worried that Southport would remain forever linked to the violence that swept across the country in July 2024.

“A lot of work needs to go into dealing with the drivers of this kind of violence, especially male toxicity,” he said. “The dialogue that we need to stop this kind of violence from happening again will have to continue for years.”

On a recent Wednesday evening, Hussein sat on the carpeted floor of the mosque’s first-floor prayer room, reciting verses from the Qur’an with three other worshippers. As they waited for the arrival of other members of the congregation for the maghrib prayer, a British-Bangladeshi man who declined to be named described moving to the town from London more than 30 years ago.

“Southport was like a paradise back then,” he said. “There were two other Sylheti families, the community was so small, everyone knew each other. People come to Southport to retire or for a relaxed life. Everyone here was so welcoming, you could leave your doors open all night with no problems.”

On one of the days I visited the mosque, Hussein showed me around the building. In the year since the riots, worshippers have been targeted in further instances of vandalism: two windows have been broken and several cars have had their paintwork scratched. The mosque is modestly funded by donations from the congregation that total about £400 each week.

Hussein showed me the mosque’s steel door, metal bars on the windows and the full-time security guard in the small car park. Until recently, three guards patrolled the area. A phalanx of security cameras now rings the building.

“There is something wrong when people who come to pray have to be so careful,” he said, ruefully. “A place of religious worship should not look like a fortress.”

Newsletter

Newsletter