Evicted in 10 minutes: what I learned from a day in housing court

Behind on rent due to family illness, benefit changes and even wrongful imprisonment, families are hauled in front of a judge to plead for their homes

It’s a few minutes past 11am at Stratford housing centre in east London and, already, three people are set to be evicted from their homes.

For the last hour, tenants — mostly from social housing and many behind on rent — have been called into courtroom 11, one after the other, each facing the possibility of losing the roof over their heads.

In the brightly lit waiting room, the tension is palpable. Quiet mumbles, nervous glances and deep sighs fill the space as people wait on threadbare chairs to be called. A noticeboard displays a long list of hearings — possession claims that, for many, mark the beginning of the eviction process and the looming risk of homelessness.

Deputy district judge Julia Smailes is hearing today’s 22 cases. Some of the defendants are dealing with disabilities or delayed benefit payments, while others are trying to plead their case in a language they barely understand. Some are simply struggling to make ends meet.

One of them is a woman who hasn’t paid rent since April 2024 and now owes her housing association landlord, Local Space, nearly £15,000.

A duty solicitor tells the court that the woman lost her eligibility for universal credit after becoming a full-time student. She now gets £4,000 a year in student finance to cover all her expenses — not nearly enough for rent in London.

Smailes grants Local Space an order for possession on ground 8 of the Housing Act 1988, which means a landlord can evict a tenant due to serious rent arrears. The woman will have to leave her home in 14 days and must find a way to pay back the £14,700, as well as £391 in court fees. Local Space — which paid its chief executive £168,000 last year — owns 1,588 homes across London and Essex.

Most cases at Stratford housing centre, tucked away at the back of the local magistrates’ court, are resolved in 10 minutes or less. The judge moves briskly and the legal jargon can be hard to follow. Many of the tenants today have arrived alone.

Next up is a young couple, also facing eviction from a Local Space home. They owe more than £5,800 in unpaid rent. The husband, a recipient of universal credit, tells the court he fell into arrears after his father in Bangladesh became severely ill and the couple used what money they had for an emergency trip abroad. They ask for an adjournment to continue paying off the shortfall, but Smailes refuses.

“They are beginning to make substantial payments towards the arrears,” she acknowledges, noting that the couple has faced “difficult financial circumstances”, but adds that this isn’t enough for an adjournment.

A possession order is granted and like many others, the couple is ushered out of the courtroom just as quickly as they were brought in. They’ve got 14 days to leave their home.

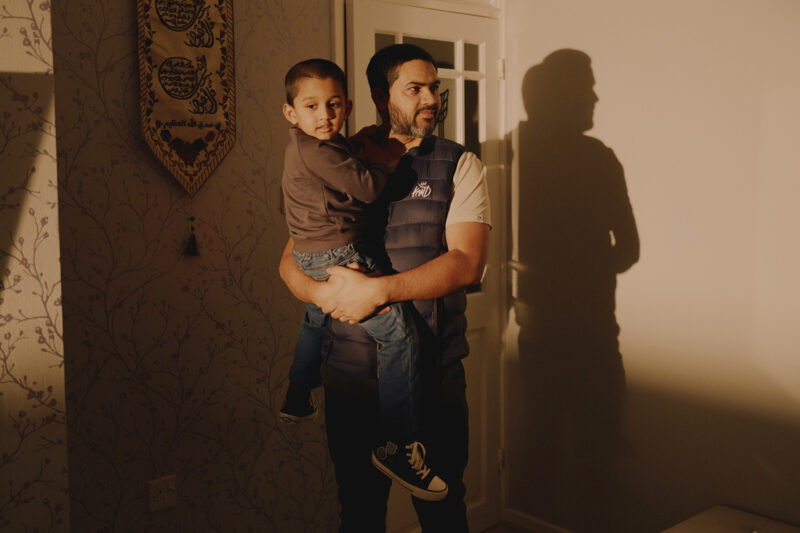

Back in the waiting room, I meet Habib Ahmed, a father of three from Limehouse, east London. He has just been released from prison after a jury found him not guilty of perverting the course of justice over a dispute with a family member. He had been held on remand for six months.

Ahmed is one of many in court today who receives universal credit, but his payments stopped while he was in prison. After his release in February, he received a backdated payment of £10,500, which he says he transferred to his landlord, Local Space, immediately. Local Space is asking for a suspended possession order, which would allow for eviction if he misses a rent payment in future. But Ahmed asks for an adjournment instead, which means that the case is delayed indefinitely so long as he keeps up with his rent payments.

Though Ahmed is still in rent arrears of more than £1,900, Smailie agrees, noting that he has “taken significant steps” to reduce his arrears and that he “has established that he is able to take responsibility”. The case is adjourned and the judge explains to him that as long as he makes the payments, he’ll be fine.

Outside, Ahmed tells me that the stress of financial insecurity — compounded by his time in prison — has worsened his depression and anxiety, for which he is now on medication.

“It’s not fair on them,” he says, referring to his wife and three children, aged one, two and six.

Ahmed says the family received between 30 and 40 letters about eviction while he was in prison. “I was speaking to my wife and she was crying, saying that they’re going to be out on the street homeless,” he recalls.

Ahmed is still concerned about how he’s going to survive financially as his benefits don’t fully cover his rent. “It’s really difficult — I have to pull out an extra £300 from the other benefits that I receive,” he says. Ahmed uses the money he gets from a personal independence payment (Pip), which is supposed to help cover the extra costs incurred by living with the painful bone condition fibrous dysplasia, to make up the shortfall.

“All the money I get goes to rent and I’m left with nothing,” he says.

In the afternoon, a man carrying a bundle of documents sits in front of the judge by himself, with no duty solicitor to represent him. His landlord’s lawyer says this service was offered to the man but that he turned it down. He now asks for a translator, but the judge tells him there isn’t one. He’s there to challenge a warrant for bailiffs to come and kick him out of the flat he has lived in since 2022.

The judge and counsel for the landlord, Ramsy Property, discuss the case while the defendant, who has a limited grasp of English, looks back and forth at them, seemingly only picking up on a few familiar words. (The lack of translators is not a one-off: in another case, a 13-year-old child waiting outside the courtroom is left to translate to her mother the decision that the family is being evicted.)

The case is a reminder of how a tenant need not do anything wrong to lose their home. When Ramsy Property sacked its estate agent, everyone whose homes the company had managed was served eviction notices. The man tells Smailes that he doesn’t understand much of the discussion, but the judge gives permission for bailiffs to kick him out by force. They will turn up in two weeks.

“You must get ready to leave and you must get advice,” Smailes tells the man. “If you need help from the council, you must go as soon as possible.” He is visibly upset and is still trying to argue his case as the usher tells him he needs to leave the court.

As the room empties out and the day winds down, 11 people have been told to leave their homes. Some walked out with the duty solicitor, desperate to ask about next steps, others alone, with heads down and shoulders tense.

An usher who has worked in the housing court for almost 37 years tells me she sees an average of around 28 cases a day, most of which are resolved quickly. Tomorrow, the court will once again open its doors to some of the UK’s most vulnerable people, and, like clockwork, more will learn if they’re about to lose their homes.

Newsletter

Newsletter