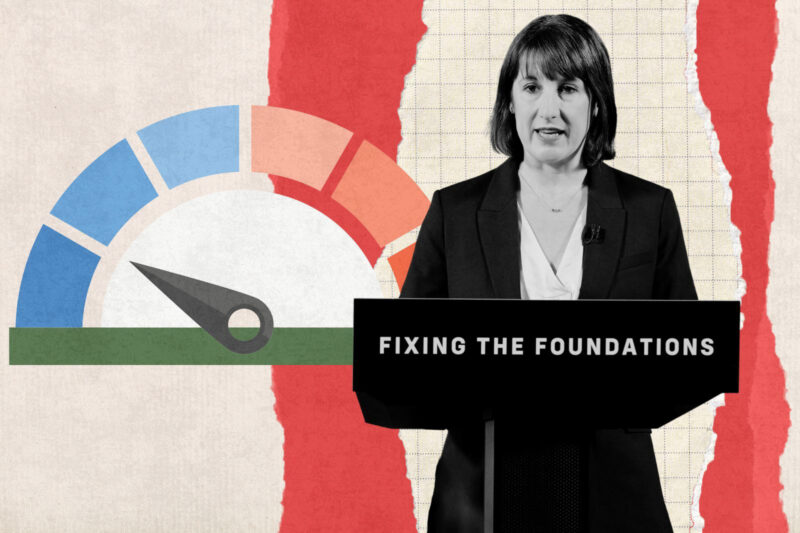

Just 6% of homes approved in Labour’s first six months were for social rent

Data from 119 councils shows that half didn’t greenlight a single council house between July and December 2024 — as 1.3m households languish on waiting lists

More than half of England’s councils did not approve the building of any homes for social rent during Labour’s first six months in government, figures obtained by Hyphen suggest, as families in overcrowded housing tell of being stuck in limbo on decades-long waiting lists.

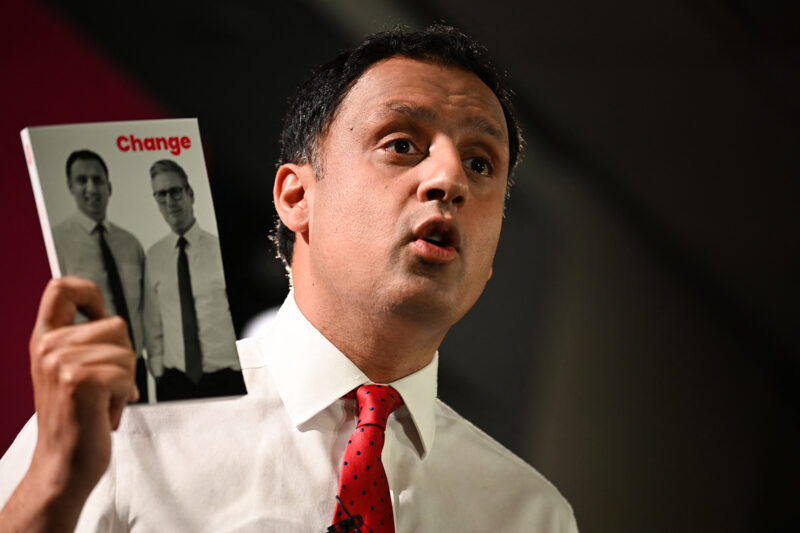

Labour pledged to get 1.5m homes built in Britain in five years while campaigning in last year’s election, but made no commitment regarding how many of these would be council houses — despite the fact 1.3m households are currently registered as waiting for them.

Campaigners and politicians from across the spectrum have called Hyphen’s findings deeply concerning, with one saying the data “flies in the face” of Labour’s big promises on housing.

A third of councils in England responded to our freedom of information requests asking how many homes had been given planning permission in the six months following Labour’s general election victory on 5 July 2024 — and how many of those were currently designated for social rent.

We found that just 6.2% (3,147) of the more than 50,000 homes approved by these 119 councils are earmarked for social rent — meaning council housing or its equivalent, where rents are set by a strict formula significantly below market rates.

Sixty of the councils in our analysis — including areas such as Luton and Slough, and London boroughs including Harrow and Kensington and Chelsea — did not greenlight the building of a single social rent home in those six months.

Photograph by Victor Huang/Getty Images

Muslims are substantially more likely to live in social rented housing than any other faith group in England and Wales, and four times more likely to live in overcrowded homes, according to the 2021 census.

Liberal Democrat housing lead Gideon Amos said: “It is deeply concerning that the Labour government has made so little progress and has no target for social housing while over 1.3m households sit on waiting lists.”

Green party housing spokesperson Ellie Chowns also called our findings “deeply concerning”, adding: “Only by prioritising investment in social housing can we begin to tackle the housing crisis.”

One full-time carer living in a two-bed flat with her two children and husband told Hyphen she’d been bidding for a three-bed council home since her son was 10. He will be 18 next month and still has to sleep on a sofa bed in the living room.

And a father living with six family members in a three-bed flat while on a council waiting list said the overcrowding had affected his marriage, his mother’s mental health and his kids’ studies.

“Labour will deliver the biggest increase in social and affordable housebuilding in a generation … Labour will prioritise the building of new social rented homes.”

Labour party 2024 general election manifesto

Photograph by Darren Staples/Getty Images

Richard Clewer, the housing and planning spokesperson for the County Councils Network and Conservative leader of Wiltshire council, also voiced alarm at our findings.

“Social housing can be more expensive [to deliver] but social rent housing for those who are really struggling, not able to support themselves, is critical because it gives them stability,” he said.

“The stability of rent means they can actually have a functioning life, because rent isn’t just subsuming everything else.”

Glyn Robbins, a housing expert and senior lecturer in community development and leadership at London Metropolitan University, said the data “flies in the face” of Labour’s vow while in opposition to “deliver the biggest boost to affordable housing in a generation”.

“Even by the shocking and appalling standards of recent years, that is terrible,” he said.

Social rent, typically about 50% of the local market rate, is determined by a government formula linked to relative local earnings and the size of a house.

It falls within the wider “affordable housing” umbrella, which includes homes for shared ownership as well as rents at up to four-fifths of the market rate — about 60% more than an equivalent social rent property. Successive governments have been criticised for switching focus from council housing and social rent homes to the more nebulous category of “affordable housing” when setting targets.

Housing experts advised Hyphen that analysing planning approvals would be a good proxy for measuring Labour’s progress on social housing during its first half-year in office.

Of the 60 planning authorities that approved no social rent homes, Sandwell had the largest waiting list.

The West Midlands council, which has one of the largest Muslim populations in England, had more than 15,000 households on its waiting list as of 31 March 2024.

A spokesperson said just four of the developments the council had approved in the six months from July 2024 had met the threshold requiring them to contain any affordable housing, and that these had “collectively secured 85 homes for affordable rent” — which could mean up to 80% of local market value. But they added that Sandwell had built 547 new council homes since 2016, and was in the process of constructing 89 more.

Lichfield and Manchester city councils approved the most social rent units of any council in England that responded to our questions — 291 and 259, respectively.

Photograph by Jason Alden/Bloomberg

Tasnim Patel, 39, is a full-time carer for her husband, and lives with their teenage son and daughter in a two-bed council flat in Batley, West Yorkshire. Their son sleeps on a sofa bed so his sister can have a bedroom.

“When I told him: ‘You have to sleep in the sitting room on the sofa bed,’ he was upset,” she said. “He said: ‘I need my own bedroom.’”

Batley is covered by Kirklees council, which had 13,920 households on its waiting list as of 31 March 2024. It said it had approved the building of 263 new homes between July and January, with nine of those earmarked for social rent.

Patel said her household income was about £1,600 a month in universal credit payments, making both “affordable” and market rents too expensive. Once they’ve paid their bills and £379 monthly rent, the family is left with about £150 a week for groceries and living costs.

“When my son turned 10, they said: ‘You can register for a three-bedroom house,’” she said. “He’s going to be 18 at the end of May. I keep bidding for houses. I sent a medical assessment for my husband, and they said: ‘It’s not enough evidence you really need a three-bedroom house.’”

Moses Crook, Kirklees council’s deputy leader and housing chief, said demand for social housing “massively exceeds capacity” and was increasing year-on-year — but that the town hall was “trying incredibly hard to help those people who are in the most urgent need as a priority”.

“When my son turned 10, they said: ‘You can register for a three-bedroom house.’ He’s going to be 18 at the end of May.”

Tasnim Patel

Photography for Hyphen by Tori Ferenc

The number of social rent homes being built in England has plummeted over the past 60 years. Some 1.24m social homes were built in the 1960s compared with just 150,000 in the 2010s, analysis by housing charity Shelter has found.

This dwindling supply has been exacerbated by the Margaret Thatcher government’s right to buy policy, which allows most council tenants to buy their home at a discount.

More than two million homes were sold through right to buy between April 1980 and March 2024, leading to a net loss of social housing in most years since 1981.

Today, the amount of affordable housing — including council homes — in a development is usually determined following a discussion between a developer and the local council.

Developers use documents called viability assessments to determine how much affordable housing they say they can afford to deliver on the site while still making a healthy profit. Councils can withhold permission to build if they do not feel a developer is delivering a fair amount of affordable housing, or doing its sums correctly.

This makes councils the de facto gatekeepers of affordable housing, even when a development is not being publicly funded. But loopholes in planning law can make this job harder.

For instance, under the government’s National Planning Policy Framework (NPPF), councils are told not to ask for any affordable housing in developments of up to 10 homes.

In other cases, under what are called “permitted development” rules, commercial properties including offices and shops can be converted into often large amounts of housing without going through the planning process at all, meaning their developers need not deliver a single affordable home.

Some parts of the country have relatively low waiting lists, in the hundreds. Even so, some of these greenlit significant amounts of council housing in Labour’s first six months.

Then there are cases like Birmingham city council, Europe’s largest local authority, which had a waiting list of nearly 24,000 households in March 2024. It granted planning permission to 5,491 dwellings, with just 131 (2.3%) designated for social rent.

Richard Parker is the Labour mayor for the West Midlands, which covers Birmingham as well as Sandwell and Coventry — neither of which approved any social rent homes in the period investigated by Hyphen.

“For too many years, there hasn’t been nearly enough investment in social housing,” he said, adding he had set a target for the region to be building 2,000 social homes a year by 2028.”

The government has pledged that construction will start on “up to 18,000 new social and affordable homes” across England by March 2027 thanks to a £2bn grant from the Treasury to social housing providers.

It will “ask” developers to prioritise homes for social rent — but has not committed to any specific targets for these.

“We have dozens of brownfield sites in our region ready for investment,” said Parker. “The government is matching our ambition by putting £2bn on the table to get places like ours building on a huge scale again.”

Labour backbencher Barry Gardiner, whose local council — Brent — told us it had greenlit 1,347 homes with just 31 (2.3%) set for social rent, said town halls “need to be much tougher and insist on getting value for the people they represent”.

Photography for Hyphen by Tori Ferenc

Aslam Khan leads the Conservative opposition on Luton council, which didn’t sign off a single home for social rent between July and December.

“We have a huge shortage of housing in general,” he said, “whether it’s affordable or social housing, because we are landlocked and there are limitations to what we can build.

“There are so many desperate families living in temporary accommodation at the moment, so many people on the register and, in all fairness, some of them will probably never get a house because we are not building enough. We are not building enough as a country.”

Luton’s housing chief Rob Roche said Luton was “often used by other boroughs to relocate individuals and families in housing need, which places further strain on our already limited housing stock and reduces availability for local residents”, and also pointed to its limited space for development.

“We are committed to finding innovative and collaborative solutions,” he said.

“Alongside our work with local housing partners, we are also engaging with private landlords to broaden the range of suitable and affordable homes available. But this is a national issue as much as a local one.”

Some councils told us they had granted planning permission to projects where the exact mix of affordable housing was yet to be established. Our analysis reflects only what councils have confirmed will be built.

Others told Hyphen they couldn’t provide the data because they didn’t hold collated figures on how many homes for social rent they had greenlit over this period.

Clewer, who runs Wiltshire council, said this in itself was a problem. Wiltshire granted 293 dwellings planning permission over the six months, with 20% (59) earmarked for social rent, our analysis found.

“If you don’t understand how much is social based on your own market figures, based on the need you’re facing, I don’t see how you could be adequately planning for housing,” he said.

“I’ve got three kids that need feeding, shopping, clothing — if I spend three grand just on rent I’m left with nothing.”

Tariq Monsur

Photography for Hyphen by Nahwand Jaff

Tariq Monsur, 39, lives with six family members at his parents’ three-bed flat in east London.

The employment adviser cohabits with his wife and their three sons, aged 16, 14 and eight; his dad, 69; and 58-year-old mum at a Clarion housing association flat in Tower Hamlets.

They’ve been living with his parents since 2007 and he’s been on the waiting list for a three-bed flat for his immediate family since April 2019.

A letter from the council, dated December 2023 and seen by Hyphen, said Monsur’s family had been “awarded overcrowded priority” but warned the average wait time for a three-bed was still 11 years.

Analysis by the National Housing Federation, Crisis and Shelter last month revealed some local authorities now have 100-year-plus waiting lists for three-bed social homes.

Monsur and his wife share a bedroom with their eight-year-old, while the two older boys sleep in bunk beds because single beds won’t fit in their room. Nor will their wardrobe.

He said his eldest has his GCSEs this year and needs his own space for revision.

The situation is “very depressing, but I can’t afford the general rent out there in Tower Hamlets because the private rent is ridiculous”, Monsur added.

“The three-bedrooms are £3,500. I’ve got three kids that need feeding, shopping, clothing — if I spend three grand just on rent I’m left with nothing.”

Tower Hamlets had a 24,519-strong household waiting list as of March 2024, dwarfing even Birmingham’s backlog despite its much smaller footprint.

Ministers claim measures in the planning and infrastructure bill, currently passing through the House of Commons, will help speed up planning decisions to boost home-building.

Most of the councils included in our analysis appear not to have a specific policy on what proportion of units in each new development should be for social rent.

Labour has revamped the NPPF to add more references to social rent and axe many of the previous government’s policies.

It now stipulates that, where a need for affordable housing is identified, planning policies should specify a minimum proportion of social rent required — but does not suggest what this should be.

Robbins claimed this left “huge wriggle room for developers to weasel and wrangle their ways out of building the homes we need”.

But Steve Turner, executive director at the Home Builders Federation, a trade body, pointed the finger at Westminster, saying the planning figures for Labour’s first six months would have been “influenced by the damaging changes to the NPPF made by [former Tory housing secretary] Michael Gove, which watered down targets” by allowing councils to treat the formula for setting local housing targets as “advisory”.

“Whilst these have now been reversed by the new government, it will take time for the results of that to filter through,” he added.

Photograph by Leon Neal/Getty Images

Shelter is urging the government to use its spending review in June to invest in 90,000 social rent homes a year for a decade.

Building these homes could add £51bn to the economy, according to a report commissioned by Shelter and the National Housing Federation, which represents social housing providers. It estimated this would create 350,000 jobs and save the exchequer £4.5bn in housing benefit payments over 30 years by moving households from private rental to social housing.

“There is a mountain of evidence that social housing pays for itself,” added Robbins. “It’s time to change course.”

A spokesperson for the Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government said: “We’re taking urgent action to fix the broken system we’ve inherited and deliver 1.5m new homes, which includes the biggest boost in social and affordable housing in a generation.

“Through our pro-growth National Planning Policy Framework, we have introduced new mandatory housing targets for councils to ensure more homes are built in the least affordable areas. This is alongside the decisive action we’ve already taken to help councils scale up delivery of new social homes and reverse decades of decline in council housing.”

Newsletter

Newsletter