‘Opening a pandora’s box’: our panel tackle the assisted dying debate

A consultant in palliative care from the British Islamic Medical Association, a senior fellow at a Christian think tank and a humanist discuss their views on the assisted dying bill

Dr Nadia Khan, consultant in palliative care, British Islamic Medical Association

Muslim healthcare professionals in the UK are confronting what it means to open Pandora’s box: death now being framed as a credible “treatment option” for those with life-limiting illness.

Much of the debate on the proposed assisted dying (or more accurately, assisted suicide) law has been an arena where nuanced perspectives have collided with dogma. The assisted suicide and euthanasia movements are harnessing conceptual frameworks of “individual choice” to justify the sidelining of traditional religious values within the debate, suggesting that those who do not agree with assisted dying are simply “free” to not choose it for themselves.

This completely misses the point that the introduction of state-sanctioned termination of life has paradigm-shifting implications for every member of society.

It will fundamentally impact the framework, structure and underpinning values of healthcare for us all — what it means to have illness, to be disabled and sick. This will influence policy, guidance, service development, resource allocation and ethics for all of us.

As a group, Muslim healthcare professionals stand out as being, in majority, opposed to assisted suicide. Most who are opposed on religious grounds also see the danger of devaluing certain lives and the types of healthcare injustice and inequities that are exacerbated, especially within the context of a healthcare system under huge strain that is already desperately failing to meet the needs of people across the country.

Care of the vulnerable, weak and sick is a deeply-held value both as healthcare professionals and as Muslims. The response to suffering, pain and distress is to build funding and services that can give patients adequate compassionate support, while providing the type of pain management that is possible in modern medicine.

The ongoing parliamentary committee stage proceedings have also dismissed amendments to the bill that would safeguard vulnerable groups. The debates have brought to light how difficult it would be to assess and identify that people are not being pressured into assisted suicide. There is now a quiet acknowledgement — and a very disturbing acceptance — that wrongful deaths will inevitably take place under the legislation.

As Muslim medical professionals, ensuring justice in healthcare and doing no harm, let alone not terminating life, are non-negotiable ethical values. The British Islamic Medical Association continues to advocate against this dangerous legislative precedent, on behalf of its membership and broader British society.

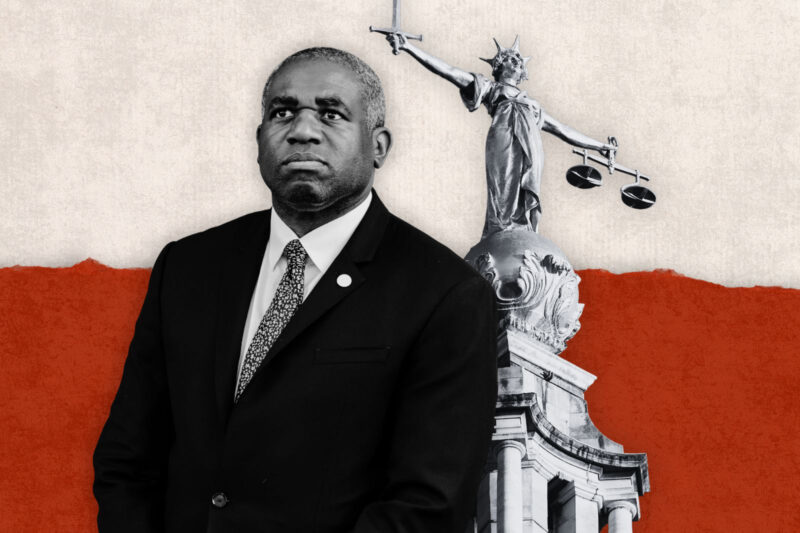

Nick Spencer, senior fellow at Christian think tank Theos

I have watched the progress of Labour MP Kim Leadbeater’s private members’ bill with reservations that are shared by many who are opposed to it.

While I fully understand the compassionate motives that energise many of those who support it, I fear that the risk of undetected coercion — particularly among lonely, elderly and vulnerable people — is simply too great to make the bill safe. The example of other countries, most notably Canada, Belgium and the Netherlands, does little to calm these fears.

If the bill does eventually become law, there will be many things on which to reflect. One of them — a minor but nonetheless significant theme — is the way in which religious arguments have been treated in this debate.

Most of the time this has been with respect, but there have been occasional blows, most memorably when Labour peer Charlie Falconer responded to justice secretary Shabana Mahmood’s opposition by saying: “I think she’s motivated … by her religious beliefs,” adding, it “obviously colours their view and is not an objective stance on things like safeguards.”

The idea that religion “colours” otherwise rational viewpoints undermines any religiously motivated opinion that differs from “mainstream” secular ones.

The latest polling for Hyphen confirms that most Muslims who oppose assisted dying (70% of the 43% who oppose it) do so at least partly on account of their “personal religious belief”. The figures for Christians are less clear cut, perhaps because “Christian” is a notoriously vague identifier in the UK. But still, all the mainstream churches are opposed to the bill, and there is good reason to believe that churchgoing Christians take a similar view.

What is interesting, in terms of the religious participation in this debate, is that just 21% of Muslims cite religious belief as the only reason for their opposition to the bill. Others cite reasons such as concern about exploitation and coercion, slippage beyond the terminally ill, and fears about the future of palliative care and NHS pressure. These are reasons comprehensible to people of all faiths and none.

However much those who follow a faith participate in this debate on the basis of religious principle, most are willing to do so in terms of public reasoning. This is encouraging for the future of public debate in the UK, but also a salutary reminder to those who would dismiss religious contributions on the basis that they are not objective or “coloured” by their faith.

Nathan Stilwell, assisted dying campaigner, Humanists UK

Last November, I accompanied a woman called Clare Turner into parliament to tell MPs how it feels to be in the final months of stage-four breast cancer, and why she wanted the choice of a dignified death. “I want to avoid pain, indignity and suffering, but I’m also aspirational because I want a good death,” she said.

When I speak to dying people, loved ones traumatised by horrendous deaths and criminalised spouses who have taken the person they love to Switzerland to die, I am continuously amazed at their determination. You expect a level of desolation, yet those who have gone through the worst can be the fiercest campaigners.

Turner says she doesn’t fear death, but she fears a horrifying end while her daughters watch on helplessly. She wants to decide the final moments of her life, hold her daughters’ hands under an oak tree in her home, and leave them with happy memories, not trauma from an undignified death.

Clare’s fear is still a reality in the UK. Even with the best possible care, 20 people a day die in pain. One person a week flees to Switzerland for an assisted death. People with terminal illnesses are more than twice as likely to die by suicide. The status quo, where helping someone out of compassion is criminalised, is beyond barbaric. It achieves nothing but misery.

As a humanist, I believe Clare should have the choice of a dignified death. All of us should have that choice. Especially when 31 jurisdictions around the world have working, safe, compassionate assisted dying laws — from Spain to the US state of Washington, Ecuador to New Zealand, almost half a billion people have access to assisted dying. In the UK, we are late adopters.

The terminally ill adults (end of life) bill would give dying people that safe, regulated option. Adults with six months or less left to live will be able to go through a safeguarded system involving two independent trained doctors, overseen by a panel of experts and extensive regulations. If they meet the criteria and are approved, they can be prescribed a life-ending medication they can take, or choose not to take, on their own terms.

While I believe we have one life and we should live it to the fullest, I also believe in the freedom to think and choose. If you’re against assisted dying, fine, don’t have an assisted death. But don’t stop me, Clare, or anyone else from choosing a dignified death.

Newsletter

Newsletter