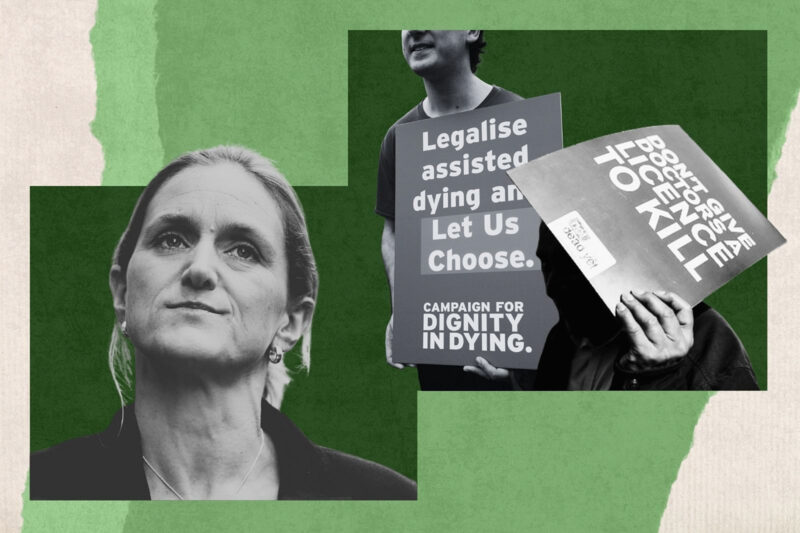

Assisted dying could push disabled people like me into an impossible choice

Covid showed disabled people what the government thinks of us. How can we trust it to safeguard us if assisted suicide becomes legal?

Life imitates art. When the UK’s assisted dying bill was proposed last year, my first thought was of Shakespeare’s Hamlet, who in contemplating suicide — “to be, or not to be” — must weigh the pain and unfairness of life against death itself.

As a disabled Muslim, my objection to the assisted dying bill is based on three things: religious belief, social justice, and a full knowledge of the reality of disabled people — or, rather, the broken system that we rely on for survival.

Covid-19 confirmed what disabled people have always suspected: we are considered lesser than the rest. Our death rate was up to 11 times that of non-disabled people. Some were given “do not resuscitate” notices. Academics and even a Conservative MP suggested simply locking us away so everyone else could go about their lives. Eventually, when lockdown lifted, those at greatest risk were made to choose between their health and livelihoods.

I was born with a degenerative muscle-wasting condition, congenital muscular dystrophy, and began using a type of ventilator with a mask called a BiPAP at the age of 13 to help me breathe. Covid terrified me. I was advised by my specialist neuromuscular hospital that, if I got ill, I should try to stay at home, and should certainly avoid bringing my ventilator into a healthcare setting. Carers couldn’t stay in hospitals, so I’d have been alone, and there was a ventilator shortage, meaning mine could have been taken and given to someone deemed more worthy. I was desperate for reassurance — yet all I got was a renewed distrust of the people who were supposed to “save” me if I became sick.

Under the proposed law, these people’s approval would be key to ending my life. But how can I trust doctors to make a decision about my continued existence who so often ignore me and talk to my companion during appointments? GPs’ knowledge is very limited when it comes to people with rare life-limiting conditions.

Omar, not his real name, is a wheelchair user with spina bifida who works in banking. He told me that he felt the bill represented “once again people telling us how we should feel, what we should do, when we should do it — now even in death”.

Disabled people have been demonised by the right-wing press in particular as a heavy burden on taxpayers, benefit scroungers enjoying free housing and transport at the cost of society. Sadly, people believe this dangerous rhetoric, and disabled people become legitimate targets for them and the government. What’s more, any disabled person will be familiar with comments such as “I would rather kill myself than live your life” or “you have all this and you are still smiling”. I have even been asked if I have considered suicide. A lifetime of remarks like these may well contribute to disabled people’s decision-making if the bill comes into force.

Like followers of many religions, I believe that taking your own life is one of the biggest sins. It is mentioned several times in the Qur’an. Anjum, who has cerebral palsy and requires round-the-clock care, feels the same. “I would want to be alive until Allah says,” she told me. “Every day, hour, minute and second of the life Allah has given me is precious. Every pain and challenge he has given me is a test.”

Being alive means enduring every test God has made us go through, and living until He decides the time is right. But I fear this belief would be tested for disabled Muslims, who may feel torn between their faith and the pressure of social attitudes towards disabled lives.

This bill, which I believe will worsen many people’s mental health, is the work of a government that is already a key force in making the lives of disabled people difficult. In March, chancellor Rachel Reeves unveiled deep welfare cuts that will primarily take money away from those who rely on disability-related benefits to survive, including those with mental health problems. Poverty, which disproportionately affects disabled people, is a driver of suicide. Add to this recipe a health service filled with doctors who are overworked, overwhelmed and underpaid, and a judge that will know little, if anything, about each individual’s home and personal life.

Disabled people, particularly women, also experience higher rates of domestic abuse. For many, assisted suicide might be the only escape; others could be coerced into it by their abusers.

I believe in people’s right to decide freely what is best for them. But this law does not represent that. If passed, it could push some of the most vulnerable people in our society into a “choice” as cruel and impossible as Hamlet’s.

Newsletter

Newsletter