Will Farage’s fighting talk translate into election success?

Buoyed by support from the Sun, Reform UK is eyeing hundreds of local council seats in next month’s polls

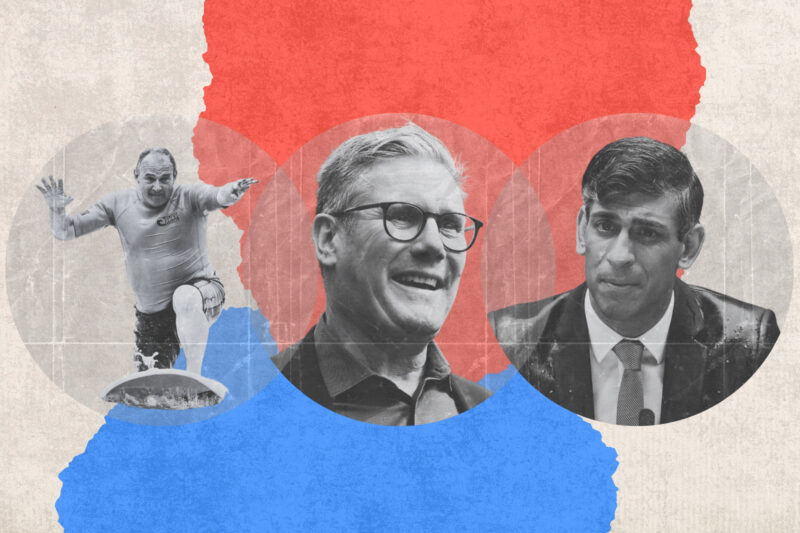

There’s a striking image doing the rounds: Nigel Farage, holding up the Sun’s front page from Tuesday with the phrase “Britain is broken” plastered on it. It’s a huge win for Farage and Reform UK, as those three words are Reform’s campaign slogan. While the Sun hasn’t officially endorsed Farage’s party, the fact that it’s running his opinion pieces and using his catchphrase on the front page makes it feel like that could be on the way.

“Our tanks are now on the lawns of the red wall,” Farage declared during a speech on Monday, signalling a direct challenge not just to the Conservatives, but also to Labour’s historic working-class base. The so-called red wall — which describes constituencies in the Midlands and the north of England that have traditionally been held by Labour — is critical to Keir Starmer staying in power. Yet for months now, Labour MPs there have voiced growing concerns to me about Reform’s rise in their constituencies.

Those close to the Reform leadership are bullish, believing they can make significant inroads in seats Labour had once considered unshakable, much as Boris Johnson did in 2019. Recent polling by Survation suggests that Reform is now the most popular party in the red wall, and that Farage is viewed more favourably than Keir Starmer. With local elections approaching on 1 May, Reform is feeling confident.

At the heart of Reform’s strategy is a deliberate pitch to the disenchanted — those who feel they’ve been ignored by mainstream parties, overlooked in the rush of globalisation and abandoned as British industry has declined over the course of decades. Nowhere is this clearer than in Farage’s rhetoric around British Steel and re-industrialisation. He has spoken out in favour of saving the plant in Scunthorpe and been critical of overseas, particularly Chinese, control of key UK industries. It’s a message aimed squarely at the Labour heartlands, invoking memories of jobs lost and communities changed.

Add to this Farage’s continued focus on issues of identity, particularly his criticism of strategies to tackle discrimination in work and recruitment (so-called “DEI”), and immigration policies that he claims disadvantage white Britons, and you get a clearer picture of the voters he’s chasing: people who feel alienated by the modern political consensus, suspicious of the elite and minority groups, and unsure of their place in today’s Britain. The strategy is, of course, not dissimilar to that of Donald Trump, a close friend of Farage.

Survation’s polling of roughly 2,000 adults in the red wall last week found that the majority said they agreed with the statements “Britain is broken” and “the country is heading in the wrong direction”. This is not a direct endorsement of Reform UK, but it is bad news for Labour all the same — it has now been in power for approaching a year, and must surely have hoped that people would by now be feeling the benefit.

Losing the red wall would likely cost Labour the next general election. For this set of what are primarily county council elections, though, the Conservatives have the most to lose. There are about 1,600 council seats in England up for grabs, with more than 1,000 currently held by the Tories. The last time these seats were contested was 2021 — a political lifetime ago. Back then, Boris Johnson was enjoying a popularity bounce, while Reform had only just shed its Brexit party label and was hardly a major political player.

Today, the landscape is very different. The Tories are less than a year on from a historic general election defeat, and not hugely popular with the public. Kemi Badenoch, in her first significant electoral test since becoming leader of the opposition in November, is already bracing for a tough set of results. “If you map that general election result of 2024 onto this coming May,” she said last month, “then we don’t win the councils we won in 2021. We lose almost every single one.”

Conservative insiders are already resigned to a rough night. Many expect the local elections to reflect the national reality: the party is on the back foot, and Reform is well-positioned to capitalise. Farage, very aware of the trouble the Tories may find themselves in, has dismissed any possibility of a local election pact with the Conservatives.

The mountain for Reform to climb, though, is steep. At the moment, Farage’s party holds about 100 of England’s 17,000 council seats, most of them originally won by councillors who changed parties after being voted in. Reform itself only stood in 12% of available local elections last year, and won just two seats in England under its own name. This time round, it’s standing in nearly all available areas and, I’m told, the party believes it can win hundreds of new councillors. Multiple figures within the Conservative party have told me they are resigned to a huge defeat and can’t see how they will be able to win back voters from Reform in the remaining two weeks before election day.

All the same, it is important to take local election results in context. Opinion polls do not always translate to electoral success, especially on a national level. The SDP-Liberal Alliance famously led national polls in the early 1980s but returned just 23 seats at the 1983 general election. Then there’s the fact that smaller parties often do better in local elections than national ones. The Liberal Democrats, for example, have outperformed their general election vote share in every local election for the past 15 years. Why? Because local elections are often decided by different factors — local issues, protest votes, and the lower psychological “cost” of backing a smaller party when national government isn’t on the line.

That’s not to say Reform’s success, if it comes, will be illusory, or without implications. Narrative matters massively in politics. Headlines about Reform gains in red wall councils will feed Farage’s central argument: that his party, not Labour, is the new home of Britain’s working class. For the Tories, it could spell further fragmentation of an already diminished base. If Reform is able to win support from voters of both major parties, its shake-up of British politics may have just begun.

Shehab Khan is an award-winning presenter and political correspondent for ITV News.

Newsletter

Newsletter