The uncompromising vision of Tarik Saleh

The Swedish-Egyptian director has gone from graffiti to film festival grand prix juries, but he is still challenging himself, his audiences and the structures of power

In a chic Parisian cafe, the Swedish-Egyptian filmmaker Tarik Saleh is sitting down amid the babble of cinema aficionados. Saleh’s surroundings highlight his journey from the graffiti-covered walls of Stockholm’s western suburbs to the silver screens of global film festivals.

The award-winning writer and director, known for his bold storytelling and distinctive visual style, is in the city as part of the international grand prix jury at the 15th edition of the month-long online MyFrenchFilmFestival.

Alongside the French-Iranian actor and producer Zar Amir, Danish-American movie star Viggo Mortensen, French actor/director Noémie Merlant and Russian writer/director Andrey Zvyagintsev, Saleh has been charged with choosing one of 20 French-language contenders for the title of best feature film.

“It gives you a sense of what the country is going through,” he says of the fresh perspectives each of the contenders bring. “When you see nine or so French films in a week, you sort of get a sense of the place, which is absolutely wonderful.”

Saleh, 52, is equally enthusiastic about his fellow jury members.

“It’s wonderful to meet other film-makers and artists,” he adds. “It is incredible to have Andrey Zvyagintsev here on the jury because he’s actually been one of my biggest inspirations.

“When I watched his first film, The Return, I realised, ‘Wow, here is a man telling a story that’s not in an Anglo tradition of storytelling, but that is technically better than the films that I see from America.’”

Saleh’s admiration for France’s unwavering commitment to the arts is also clear.

“France has something that most other countries don’t. They have a political will to support culture,” he says, suggesting that such state-level backing is the cornerstone of the country’s influence on cinema around the world.

On a more personal note, Saleh says he views each film he makes as an act of empathy and an opportunity to take the viewer into the lives of others.

“[You don’t have to be] a French teacher, a divorced mother of two, or a student at an Islamic university — cinema allows you to make decisions as if you are them,” he says.

Saleh’s artistic journey started as a graffiti writer in the late 1980s and quickly progressed to him becoming one of Sweden’s most prominent street artists. His mural Fascinate, created when he was just 17 with fellow Swedish graffiti pioneer Circle, sits to this day in an industrial park in Stockholm. It is one of the world’s oldest surviving graffiti pieces and is protected under cultural heritage laws by the Swedish government.

“I fell in love instantly,” he says, smiling as he recalls the enduring lessons he learned from his time among the spray paint and urban sprawl. “Graffiti taught me not to ask for permission to create — don’t ask for permission to do your art.”

That do-it-yourself ethos runs deep within Saleh’s film-making, but the road to recognition has not been smooth. His first two fictional films, Metropia (2009) and Tommy (2014), failed to make a mark at the box office, leaving him questioning his future.

“By the time you’ve made two films that don’t make money, it’s sort of over,” he says.

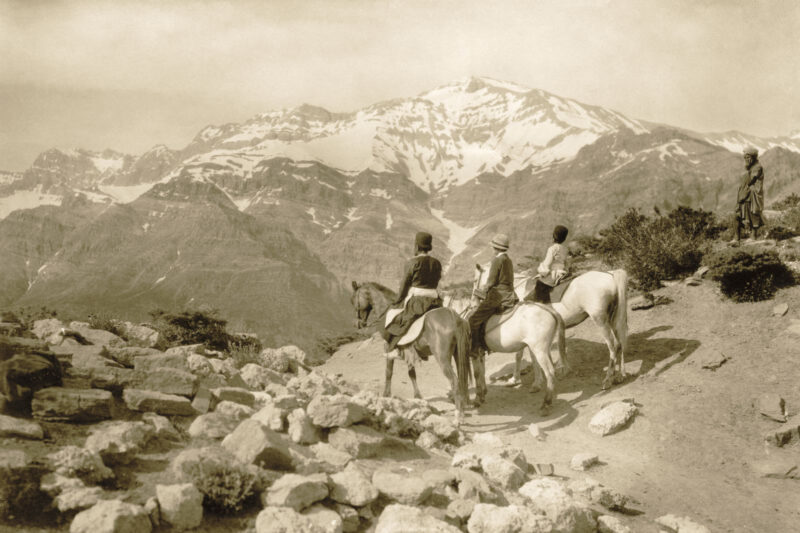

His third production, however, marked a turning point. A political thriller set against the backdrop of the 2011 Egyptian revolution, The Nile Hilton Incident (2017) was greeted with international acclaim and brought Saleh back into the spotlight as a director.

Reflecting on his creative process, Saleh highlights the importance of growing to love every aspect of film-making, from scripting and shooting to the more mundane matter of financing. His approach is almost meditative, treating each phase of production as crucial to crafting a believable and engaging narrative.

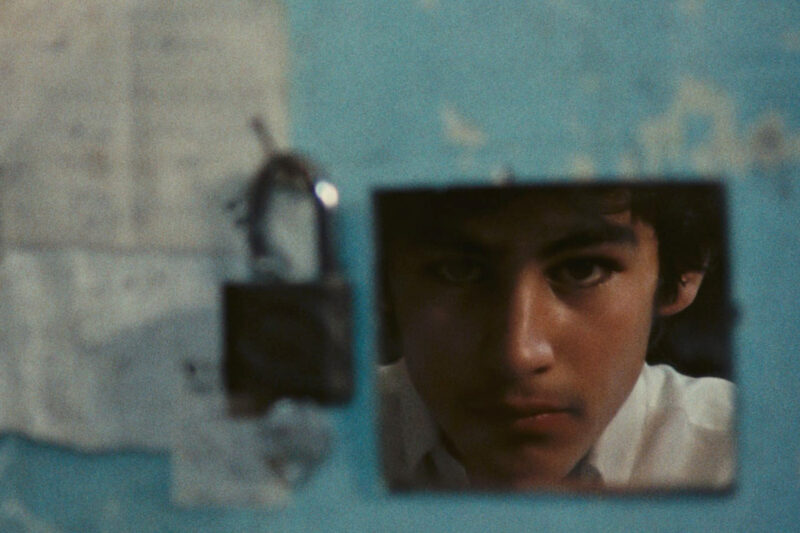

That attention to detail is evident in Boy from Heaven (2022), a political thriller in which Saleh sought to portray the rituals of Islam in a way that has rarely been attempted on screen. In order to avoid what he describes as “lying with the camera”, Saleh shot the whole project using a single 40mm lens.

“The whole film is a conflict because, especially in Sunni Islam, we don’t depict these things,” he says, touching on the challenges and complexities of portraying religious and cultural practices within a dramatic context.

Looking ahead, Saleh says that his forthcoming thriller Eagles of the Republic, scheduled for release later in 2025, is his most ambitious work yet. Forming the final part of his Cairo trilogy, along with The Nile Hilton Incident (2017) and Cairo Conspiracy aka Boy From Heaven (2022), the thriller aims to tackle complex issues at the heart of Egyptian politics and society.

Eagles of the Republic began shooting in the summer of 2024 with a $10m budget, making it one of the most expensive Arabic-language movies ever made. Details about the plot are scarce and Saleh is somewhat cryptic in his answers, but it is clear that he wants this film to challenge himself, his audience and the systems that control and shape our lives.

“You could say it takes on the highest part of the Egyptian power structure. People might think the relationship to religion is the most sensitive issue in the country — but it’s not. That’s what this film is dealing with.”

Newsletter

Newsletter