‘I want my expedition to speak for Afghan women’

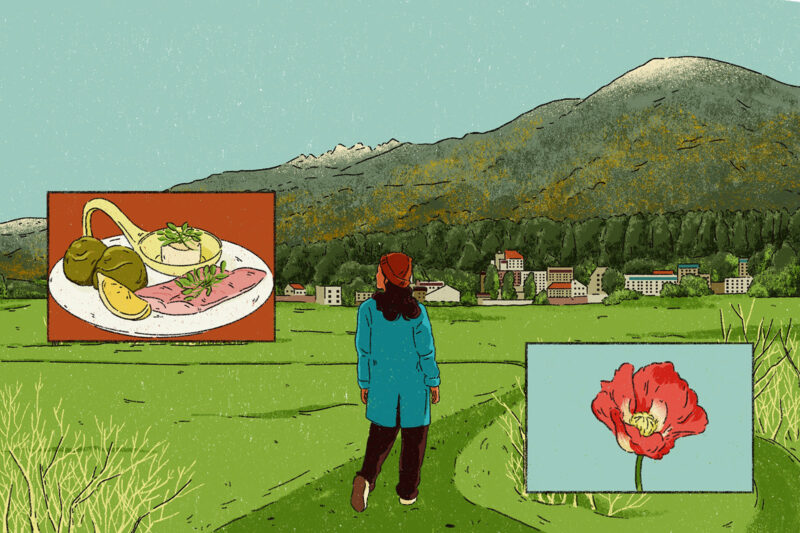

Afghan mountaineer Freshta Ibrahimi hopes to become the first woman from her country to summit Everest. She says her climb is an act of resistance against the Taliban

In the misty ranges of the Peak District, 32-year-old Freshta Ibrahimi is telling me about the mountains of Afghanistan. Specifically, about a mountain she never got to climb, and still dreams of scaling. Koh-e-Mikh is located in her parents’ province of Bamiyan. “It’s steep like a needle,” she said. “And there are many legends about witches and magic around it that fascinate me.”

A mountaineer and women’s rights activist, Ibrahimi spent nearly five years travelling across Afghanistan, leading expeditions of women trekking its peaks. “In every province, we saw women working in the fields, herding the livestock.” The idea that being outdoors was taboo for women vanished. “It’s only when we want to do something for pleasure that it becomes off limits.”

In 2019, an uptick in the decades-long conflict between the Taliban and US and Afghan government military units forced Ibrahimi to seek asylum in the UK, where she now lives. For the last year, she has been training and raising funds for her mission to become the first Afghan woman to summit Mount Everest. Since taking control of the country in 2021, the Taliban government has banned women from studying, working and being part of public life. For Ibrahimi, the trek is an act of resistance against this steady erasure. “The more they try to push us down, the higher we have to go.”

Mountains and a place of freedom

Ibrahimi grew up in the shadow of the mountains encircling west Kabul, where her family returned after living as refugees in Iran. She was 10 years old. “They were right outside our door,” she said. Her parents kept a few sheep, she recalled, and her mother liked to take them out there often, enjoying the exercise. The children helped, looking out for landmines — a legacy of Afghanistan’s decades of war — as they walked.

The sixth of eight siblings, she grew up determined to get an education, rather than be married off like her elder sisters. She attended school while also learning English at a small private institute near her home. Soon, she was teaching there. In 2012, Ibrahimi managed to secure a fully-funded scholarship to attend the prestigious American University of Afghanistan in Kabul. “I was the first to do this in my family. When I got the news, I felt, ‘Now I am free. Nobody can force me to get married or do anything I don’t want to do.’”

In 2015, while still in university, Ibrahimi came across a job with Ascend, a US-based non-profit organisation that took young Afghan women on mountaineering expeditions to build their leadership skills. She was already interested in sports, but once she began working she learned how to climb with equipment, and alongside a team. This, she said, changed her approach to the outdoors.

It was a dangerous endeavour in a conservative society, but Ibrahmi relished the challenge. “I would encourage other girls to join the expeditions, and convince their parents they would be safe. Often they would say, ‘If Freshta is with you, you can go.’”

Mountains became her escape, her place of freedom. For several months after she began, she didn’t tell her parents about her job, or how deeply she was involved with mountaineering. “Finally, before leaving for a long expedition to Panjshir, I sat them down and said, ‘This is my life now.’”

A walk in Derbyshire

Unlike Ibrahimi , the outdoors is not a natural habitat for me. Soon after I arrived in the UK from India last winter, I joined a family holiday in the Lake District. It was February, and I imagined cosy cups of tea while gazing at Cumbria’s scenic peaks. Maybe a walk by a lakeside. That dream evaporated when I realised that my brother had planned hikes up the famed fells of Lakeland. The climb was a new experience for me — even as a privileged Indian woman, I had barely any experience of engaging with the outdoors for leisure. On holidays, I saw the hills as passing scenery in a car, or through gentle strolls with my cousins. Walking in the wilderness, that too for leisure, did not feel like an act of freedom — it was a risk, a trespass. It meant being where I was not supposed to be.

In the UK, where the outdoors are ostensibly for all, many of these barriers disappeared. But subtler barriers of gender, race, and class persisted. So when I heard about Ibrahimi and her mission to climb Everest, I wanted to see for myself what she found in the outdoors — a space where I felt like a complete outsider.

Ibrahmi’s attempt intrigued me in part for its audacity. She was foreign not only to the UK, but also to the heritage of mountaineering, an industry historically enmeshed with colonialism, conquest and privilege. I was also drawn to the comfort with which she traversed the English countryside. If she could find a sense of home in the outdoors, I wondered, could I?

I wrote to ask if I could walk with her up a mountain — one considerably smaller than Everest — to talk about her mission. Soon, I was sitting across from her in a train carriage in Manchester, heading towards Edale, on the edges of the Peak District National Park.

We began in the morning, arriving in Edale at 9am. The fog thickened as we left the station and made our way up a country road. I followed Ibrahimi’s slight silhouette, guided by her bright orange backpack. The route was quiet, with occasional ghostly figures emerging from the gloom — fellow walkers who went past with a quick hello.

We were going up Mam Tor, the “mother hill” of Derbyshire, in the heart of the Peak District. The area draws a large number of tourists and outdoor enthusiasts, and many head to Mam Tor for a day trip. A metal sign on the trail gave a snapshot of its history:

“It was the home of ancient Celtic peoples, 3000 years ago.

Burial mounds have left their secret since the time.

When bronze was first worked,

And a fort once stood proudly on the summit.”

It was also, I learned later, not a mountain at all, but technically a hill.

The path up was muddy, with large rocks forming a rough scaffolding for my ascent, which would take around four hours. I had read about the spectacular views, but all I could see was grey. Ibrahimi, though, stopped frequently along the path, kneeling to look at the flowers, the spider webs glistening with delicate constellations of dew, the moss and the mushrooms springing up from the earth. After one particularly long inspection, she got to her feet laughing. “That is not an insect. It is a pistachio shell.”

The landscape we were walking through has become familiar to Ibrahimi. After leaving Afghanistan, she chose to make her home in Manchester in part because of its easy access to the hills. “By 2019, in Kabul, we were facing big problems going out with our team on expeditions, and the security situation had become very tough.”

She was married by then, to a young filmmaker from Bamiyan whom she had met through her work with Ascend. “I had contacted him for help in climbing Koh-e-Mikh. He discouraged me, saying it would be difficult to achieve in that season.” In response, Freshta had asked him: “Are you underestimating me?” From there on, their romance blossomed and they married in 2018. But their time together in Afghanistan was brief. In 2019, Ibrahimi came to the UK for a mountaineering event. “I had been abroad many times, but never thought about not returning home.” This time however, she made the difficult decision to seek asylum. Her husband stayed in Afghanistan, joining her only in 2023.

As a newly arrived asylum seeker, Ibrahimi was given temporary accommodation in Hartlepool. Over the next two years, she faced the isolation and uncertainty that comes with being a refugee, trapped in a bureaucratic limbo. The Covid-19 lockdowns made things worse. “I would think, ‘What have I done? I am living in a hostel with hundreds of other women, and the process is never ending.’” What saved her was the outdoors. When restrictions were lifted, she said: “I would pack my lunch and leave the hostel and start walking, just staying in parks or the countryside, so that I would be too tired when I came back at night to think. Outdoors was the only place I would feel like myself, where I would feel free.” It was around this time that her Everest dream took shape.

In 2021, Ibrahimi joined a masters programme for Outdoor Studies and Health at the University of Cumbria. To her surprise, she found help from people who knew of her love for climbing, and her work in Afghanistan. “The outdoors community has always supported me,” she said, “from finding a job to a place to live to helping pay the fees for my course.” In August of the same year, as the Taliban took over Afghanistan once again, Ibrahimi’s paperwork was processed, and she received the documents that allowed her to travel. “The first thing I did was to draw a picture of Everest. ”

Learning a new language

In the mainstream media, refugees are often presented as powerless figures, defined by their trauma. They are voiceless, expected and permitted only to speak of their exile. Or they are objects of pity, outsiders who struggle to belong. For Ibrahimi, the sense of dislocation vanishes when she is outdoors. “I feel confident, like I am in a place that I know well.”

But despite her love for the outdoors, it has not always been an easy journey for her in the UK. “There are places I would be worried about going alone, because maybe my English is not good enough. For example, I would not pitch a tent,” she said, nodding at a bright red one by our path, “because I would not be sure if I was allowed to do it. I would try to go with someone who knew what to do.”

There were also more subtle barriers to belonging. “My friends who are from here would ask what I did over the weekend, what route did I complete, what app did I use. And I would think, ‘ I don’t know, I just walked and when I got tired I came home.’ I had to download the apps and learn the jargon so I was able to talk to them. It’s like learning a new language.”

The day before, in Manchester, I had asked Ibrahimi what I should wear for our walk. I was unsure about my shoes, my appearance, about not having expensive gear I felt the outing required. “What you are wearing now is fine,” she said, looking at me. “ It’s more important for you to be comfortable and safe, to feel like yourself.”

I had thought then of women I had once seen on the beach in Udupi, a coastal town in southern India, wading into the sea in their saris. And I thought of the ridicule such images often evoke, as well as the joy on the faces of the women as they enjoyed the swell of the waves. I thought of all the times I had passed by a trail because I was alone, or because I thought such activities were “not for me”. The night before our walk, I had barely slept, lurching from nightmare to nightmare about getting lost, or getting hurt, or pulling Ibrahimi down a steep ravine, or looking ridiculous in so many possible ways. It’s like learning a new language, I had told myself.

We were walking on the edge of a ridge, and the sun broke through patches of the mist. I watched my breath appear in vapours as I struggled to find a footing on slippery rocks. The summit seemed mysterious and far-away, circled by the faint outlines of birds.

I was starting to enjoy the sense of isolation and being removed from city life when I saw more figures emerging from behind the ridge. A woman walked past me in her slippers, clutching a cup of tea. I realised then that we were on the path to the summit, that was almost comically close to a car park. A few paces ahead, Ibrahimi chatted with two sisters, tourists from eastern Europe.

The path was also marked by signs of this human passage: from the cairns arranged by the wayside to plastic debris. Looking down, I saw metal plaques depicting objects found around the hill, including an iron age plough. On a clear day, I had read, you could see Manchester from up here, and a road had once run from Mam Tor to Sheffield before being disrupted by landslides. The names of both cities evoked a moment of vertiginous connection for me. I thought of the steel mills of Sheffield and the cloth mills of Manchester, of the movement of goods and migration of people from the margins of the erstwhile British empire to its industrial centre. The idea of remoteness, I realised for the second time that day, can often be an illusion.

Mam Tor’s 517m summit is marked by a trig point — a small stone tower. That morning, it was surrounded by a group of toddlers wearing woolly hats and walking boots. There were also clutches of adults waiting for their turn to take photos. Walking away from this unexpected and colourful crowd, we found a spot at a ledge nearby and unpacked our lunches. For Ibrahimi, shop-bought sandwiches, and for me, kebabs and a paratha, packed by my cousin in Manchester.

Throughout our conversations, I had been struck by the placidity with which Ibrahimi shared her seemingly impossible ambition to scale Everest. But behind her calm assessment of her plans is a ticking clock. Climbing season for Everest opens in the spring of 2025, and Ibrahimi needs around £40,000 to make the attempt. She is crowdfunding her effort and has secured some support: an outdoor clothing company has donated some gear, and other mentors and friends have helped her travel to different training expeditions, including scaling peaks of more than 5,000-6,000m in Chamonix, Nepal, as well the Everest base camp. But to summit the 8,849m mountain is expensive, and Ibrahimi still needs to raise more than half her target.

I asked what she was worried about the most other than the money. “Weather related accidents,” she said. “And the traffic.” More than 600 climbers summited Everest in 2024, adding thousands of support staff to the mountain. The overcrowding has led to a number of challenges, including long, dangerous queues. Last year, eight people died while attempting the climb. “Every one of us on the path is worried about the queue,” said Ibrahimi, “and each of us is adding to it.”

Accessibility and the outdoors

The history of climbing mountains is deeply entwined with the legacy of colonialism, its narratives shaped by tales of heroic white men “conquering” these peaks. This is strikingly clear in the mythology that surrounds Mount Everest, where the immense contributions of local communities have often been erased. Ibrahimi is stepping into this heritage in her very ambition to climb mountains as an Afghan woman. On the top of Mam Tor, we were the only women of colour I could see.

As we prepared to leave our perch on the ledge, I took in the cold breeze, the expansive sky and the space I sensed rather than saw below. A few weeks earlier, the Taliban had banned women from going to Afghanistan’s parks, and even from speaking in public. “Going outside, feeling the fresh air, talking to each other — this is all important for us to be human, to be able to process trauma,” Ibrahimi said. “Is the life of these Afghan women not important? I want my expedition to speak for them.” The name she has chosen for her attempt is Omid, a Persian word meaning hope.

We made our way down from the summit, the path now an easy descent. I was relieved at having reached the beginning of the end, already thinking of hot tea at the cafe by the train station, of the pleasing sense of accomplishment that would ride with me back to Manchester. Ibrahimi stood by the roadside, phone in hand. She was looking at another trail she hadn’t explored yet, that would be a longer, circular walk back to our destination. “Should we take it?” she asked me. We crossed the road and stepped onto the new path.

The trail led us on the moors, and we walked in a narrow ravine, the earth rising around us to give an impression of a channel. The sound played tricks and I heard my own footsteps coming from behind me. A few men on bikes passed us by, mud flying in their wake. The heather changed colour with every few steps. It was as English a landscape as I could have imagined.

The ravine gave way to a path scattered with stones, with rivulets of water forming little barriers for us to negotiate. There were also other borders: stiles and hedgerows marking off private farmland from the public pathway. For all its illusion of being open, the access to the land we were on was carefully controlled.

I asked Ibrahimi what she had felt during last summer’s riots, when asylum seeker hostels and accommodation were targeted. The riots had started with false claims that the killings of three children in Southport were committed by a Muslim immigrant.

“I was surprised at the intensity of the violence. But I was not surprised at the violence itself, because I have been through the system, and it makes you understand that you are not wanted here.” Since 2023, she has been working for a charity in Manchester that provides refugees and asylum seekers with mental health support through working in a community garden. When the violence broke out, the organisation had to stop their activities for a few days. “We also had to cancel our planned trip to the seaside. In fact, we were supposed to be going to Southport. ”

After Everest, Ibrahimi wants to continue opening up the outdoors to people on the margins. “Afghan women and many other refugees lack the confidence to go outside here, they think they don’t have the skills, or feel unsafe, or worry that they will face hostility. I want to be the bridge for them — and help them enjoy nature in whatever way they want.”

A few steps ahead, the fog miraculously lifted. In an instant, the route was transformed, and the panorama of the valley broke through in dramatic splendour. We scampered up the grassy bank for a better view, and gazed at the sprawl of the valley below us, the sun picking out the spires and roofs of a small village. Two women walked past us, nodding greetings. We watched until the fog muddied the horizon once again.

Preparing for Everest

Over the past two years, Ibrahimi’s life has taken on some sort of routine. During the week, she goes to work at the community garden and on weekends, she trains for her climb up Everest. But the deadline she faces is always on her mind: the seasons slowly turning towards spring, and the mountain opening. The week after our walk, she was due to make a presentation of her plans at an outdoors festival, hoping to raise funds from an audience of corporate sponsors and outdoors enthusiasts. But before that, she had a pick out dress for her graduation. And that evening, she was invited to a birthday party of her friend’s grandson. Slowly, she was creating a home.

We came off the trail, on the road leading back to the station. It was almost dark, and Ibrahimi told me to walk on the side of the road facing the traffic, a tip she had received from other walkers. “People drive really fast in the countryside,” she said. “It’s more dangerous to walk here than in the cities.”

At the top of Mam Tor, sprawled in the wet grass, I had asked Ibrahimi what she would do when she stood on the peak of Mount Everest. Would she hoist a flag, or leave some kind of token? “I don’t want to leave anything there,” she said. “When I went to the base camp in 2023, I had taken away a small stone with me. I want to take it back, leave it where it belongs.”

Newsletter

Newsletter