‘If we do nothing, this is where we’re heading’: Asif Kapadia on his dystopian vision of the future

Kapadia’s new sci-fi documentary is a sombre warning of a world controlled by authoritarianism and tech moguls. He speaks to Hyphen about the motivations behind the genre-bending 2073

Asif Kapadia has a grim vision of the future. Drones and surveillance cameras populate the skies of a landscape coloured by desert yellow hues. Machines have taken over humans in a post-apocalyptic setting with few survivors who live in fear of militarised police.

Broadly inspired by Chris Marker’s radical 1962 science fiction short La Jetée, 2073 is the award-winning director’s new hybrid sci-fi documentary depicting a dystopian future not so dissimilar nor far from our present world.

“It sums up what I feel right now about the world and politics, and what is happening in technology now. If we do nothing, I think this is where we’re heading,” Kapadia tells Hyphen over a Zoom call from London, ahead of the film’s UK release on 1 January.

In Kapadia’s envisioned world, viewers are led by Samantha Morton as Ghost, whose sombre voice narrates inner reflections on the state of the world following an unnamed apocalyptic event in 2036. She appears to be an embodiment of Kapadia’s concerns. “People thought the world would end. But the world goes on. It’s us who will end,” Morton states, over graphic images of a Palestinian man being tasered to the ground by Israeli soldiers.

It is a disturbing idea of the future, but one Kapadia has been grappling with for the past decade, haunted by increasingly powerful tech moguls, the climate crisis and rising authoritarianism.

Like many in the UK, Kapadia’s worldview changed drastically in 2016 during the Brexit referendum when anti-immigrant rhetoric and far-right narratives proliferated, spread by a wave of disinformation on social media. That same year, he spent time in the US as a show runner on the Netflix series Mindhunter, where he saw Donald Trump’s first electoral campaign succeed up close — an event he wasn’t surprised by.

“The language was exactly the same as the Brexit messaging,” Kapadia recalls, referencing the nationalistic slogans used in both countries during the campaigns. It was during this time, when he “started to question what the hell is happening”, that the idea for 2073 began to take form.

A few years later, during the Covid-19 lockdown in 2020, he began reaching out to journalists and academics around the world, asking them the same question: are things getting better or worse?

“They said: ‘No, it’s all getting worse’, and the reason is tech. The reason is social media. The reason is WhatsApp. The reason is Facebook. The reasons are all these forms of technology which basically take you down rabbit holes.”

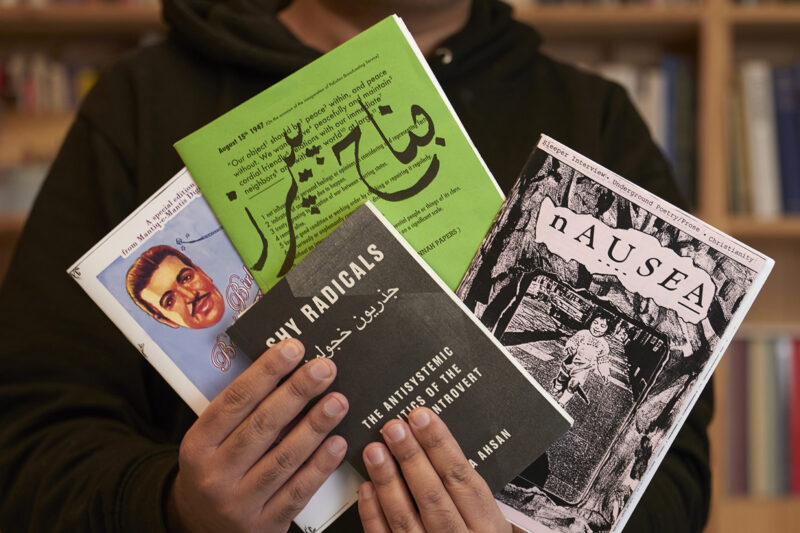

Renowned human rights journalists act as implicit protagonists in the film. There is Carole Cadwalladr, who exposed the Cambridge Analytica scandal in 2018; Rana Ayyub, who documents religious violence and extrajudicial killings under prime minister Narendra Modi in India; and Maria Ressa, who won a Nobel peace prize in 2021 for her defence of a free press in the Philippines.

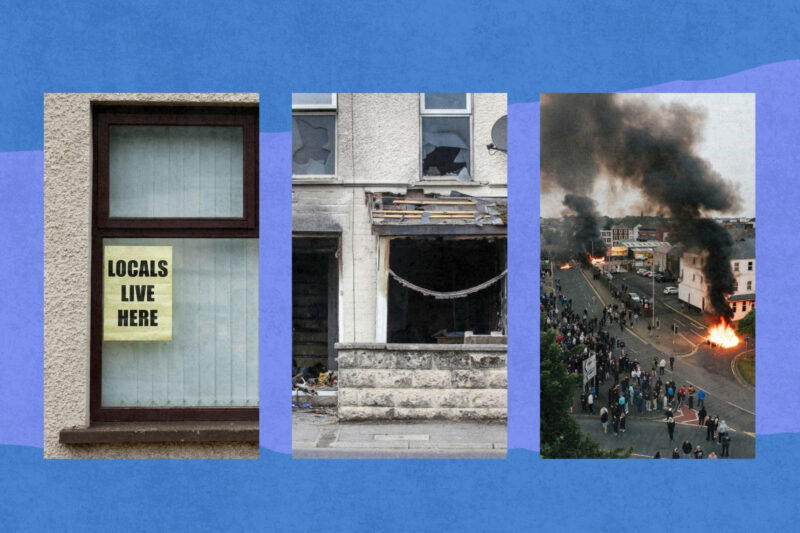

Their stories and voices are interspersed throughout, and the result is a feature blending dramatised sci-fi with contemporary news archive. Scenes of the future are interrupted by footage of protests being suppressed in Hong Kong and Chile in 2019, white supremacist movements coming out from the shadows under Trump, and Islamophobic violence on the rise under Modi.

“My intention has always been: can I make a feature film that people who don’t like documentaries will go and see?”

This accessible approach applies across Kapadia’s films. He is best known for his trilogy of narrative, archive-constructed documentaries Senna, Diego Maradona and Amy — for which he won an Oscar in 2016 — producing detailed, sensitive portraits of individual subjects. In 2073, he is not exploring individuals, but global issues that affect us all.

“If there’s a theme that runs through my work, whatever the genre, whatever the subject, it’s films about people taking on power in one form or another, or dealing with a powerful system,” he says. “Even Amy, she’s dealing with the entertainment business, the media and paparazzi, and Senna was taking on Formula One authorities, and Diego Maradona was taking on the power structure in Italy, and in this case it’s journalists taking on world leaders and power.”

Kapadia’s work and outlook is deeply rooted in his own upbringing. Raised in a working-class household to Indian Muslim parents in north London, he grew up surrounded by diverse communities and languages.

“I was always interested in seeing the world, and I thought the way of doing that is to work on films, where you meet so many people. The more you travel the more you realise how much people have in common.” Kapadia believes these issues of division come “from people who don’t see the world. They always have a problem with immigration and with different religions. They have a problem with boats. They want to build a wall.”

So it felt natural for him to make films “as international as possible”. His first feature The Warrior is in Hindi, Diego Maradona in Italian and Spanish, and Senna in Portuguese, a rare feat for a British filmmaker.

Born in 1972, Kapadia entered the film industry as a runner in London in the 1990s, at a time when he felt “there was this idea of democracy going everywhere. The Berlin Wall comes down. Nelson Mandela gets released. The world is kind of getting better. And naively I thought that would continue happening. Everyone would be freer.”

Today, with his children aged 17 and 13, Kapadia holds a more cynical mindset: “What is the world going to be like when my kids are my age or a bit older? What is going to happen to them if I don’t speak up now?”

In recent years Kapadia has turned to social media to speak out against policies that restrict the right to protest or attack minorities, as well as calling out Israeli crimes in Gaza — although he’s now left X (formerly Twitter) since the Elon Musk takeover. What frustrates him the most are how western leaders abuse democracy, and how so few people — particularly artists like himself — are using their platforms to speak out.

“The people who are meant to be in charge are not stopping it; they’re helping it, they’re making it happen. So then you’re like: ‘Well, I can’t vote for you people. I can’t say that you represent me.’”

He urges people to take it upon themselves to ignite change. “We have to educate our parents. We have to change the way we live. We have to speak up. A lot of people have kept their mouths shut because they’re worried what would happen if they said something. And I think that’s the problem.”

2073 does not strive to give hope, but to show how bad things currently are and how bad they could still get. “It’s bleak, but the twist is, if we start doing something now, 2073 hopefully will be much more positive.”

Newsletter

Newsletter