Dutch Moroccan artist Sarah Amrani wants to reframe the hijab

Terror of Beauty, on show in Amsterdam until February, explores the particular scrutiny Muslim women face in the digital age

What makes a face perfect? Symmetry and proportionality, the digital voice of a beautified hologram tells visitors to Sarah Amrani’s debut solo show Terror of Beauty. The exhibition, which is on at Foam in Amsterdam until 26 February, explores the Muslim experience of online algorithms that favour western beauty standards.

The hologram’s face, projected onto a mannequin head, appears perfect when standing directly in front of it, but from any other angle, the image fragments to reveal a beautifying filter on top of the face. A hijab that should frame the face remains constant and unchanged in a separate corner; a reminder that while facial features can adapt to the western gaze, the hijab cannot.

“By placing the hijab within the context of AI-driven beauty filters and virtual identities, I open a dialogue about how various cultural traditions relate to the challenges and opportunities of the digital age,” Amrani said.

The show’s title, Terror of Beauty, is not a reference to state terror, she explains, but a critique of society’s pursuit of beauty at any cost, establishing the face as a “battleground”. The hijab here is not only a religious or political symbol but a visual frame in which Amrani explores the particular ways that the appearance of Muslim women is scrutinised.

It was this new perspective that drew Foam curator Aya Musa to Amrani’s work. “It’s something you don’t see often in museums or cultural institutions in the west,” Musa said, adding that discussion around the hijab in Europe is typically negative. Amrani, Musa explains, sees the hijab as “a means of independence and a supremely powerful tool of female empowerment”.

Amrani hopes the show will help humanise Muslim women in the Netherlands, where she lives and works. The Dutch government introduced a burqa ban in 2019, restricting face coverings in public spaces. As the political mainstream has embraced the far right, the Dutch Moroccan community in which she was raised has become increasingly ostracised from mainstream politics. Muslim women in particular have become politicised and marginalised.

She wants to offer a counter narrative, challenging stereotypes and reminding viewers that Muslim women actively participate in contemporary beauty, technology and identity discussions. She is fascinated by the hijab’s “contradictory” role in the beauty blogosphere, where hijabi women are under pressure to conform to their own beauty standards. “We are all victims and perpetrators in the pursuit of beauty,” she said.

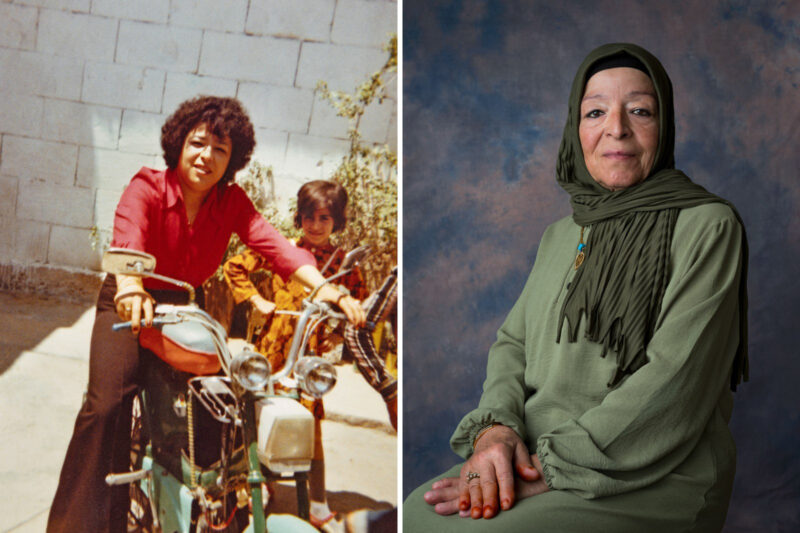

Now based in Rotterdam, Amrani, 30, was born in Amsterdam to Dutch and Moroccan parents. She had a religious Muslim upbringing and the tension she experienced between traditional and modern culture is central to her work. She has a multidisciplinary approach to her art, using photography, film and found footage. Islamic traditions and bicultural identity have been guiding themes throughout her career.

Her photo series Oujda, exhibited as part of a group show at the Cobra Museum of Modern Art in 2022, explores Moroccan wedding traditions of a girl waiting to meet her fiance for the first time. The woman’s face is obscured but we see her in multiple dresses, a reference to the seven gowns Moroccan women wear on their wedding day to symbolise purity.

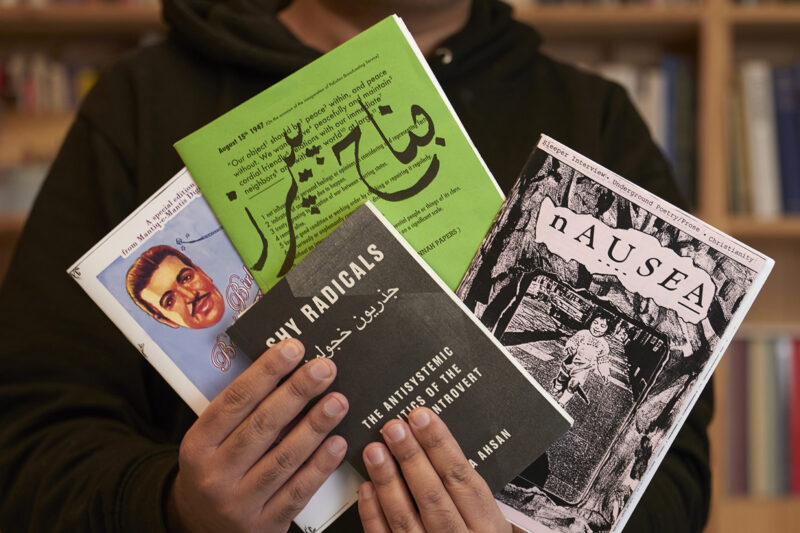

Amrani previously critiqued the idea of a perfect face in her project #Beautification, which showed in Casablanca in 2018. Beauty for Muslim women has historically varied across cultures, she argues, but online, the scope for individuality is narrowing. Social media platforms systematically promote images of Muslim women exhibiting westernised aesthetics, Amrani has observed, while expressions of individualism are less visible.

She points to tools like Anaface, which ranks facial beauty and suggests potential improvements, and the “Instagram face” phenomenon in which ethnically ambiguous features are collaged into one “ideal” face through cosmetic procedures or digital manipulation, fostering insecurity in women and girls whose natural features don’t match the archetype. As a result, Amrani believes Muslim women are under greater pressure to alter their natural features.

“When it becomes an online calculation, it reinforces the same ‘copy paste’ face,” she said.

Social media platforms are beginning to recognise this issue. In November TikTok announced a ban on beauty filters — many of which alter skin tones and experiment with surgical manipulation — for users under 18 to reduce pressures around beauty standards.

Through Terror of Beauty, the artist wants us to consider the positive potential of this same technology. At the centre of the exhibition is a mirror with facial geometry mapped out on it and facial markings of the Amazigh, an ethnic group indigenous to north Africa. By scanning a QR code, visitors can apply a filter with these same markings and experience how north African women have historically practised beautification outside of western norms. “I’m not trying to say social media filters are only good or only bad,” Amrani said. “I want to show how technology creates new possibilities for self-expression.”

Sarah Amrani’s exhibition Terror of Beauty runs at Foam, Amsterdam until 26 February 2025.

Newsletter

Newsletter