‘This is our legacy’: Peter Sanders on 50 years photographing the Islamic world

The British photographer converted to Islam in 1971 and has since dedicated his life to documenting Muslims globally

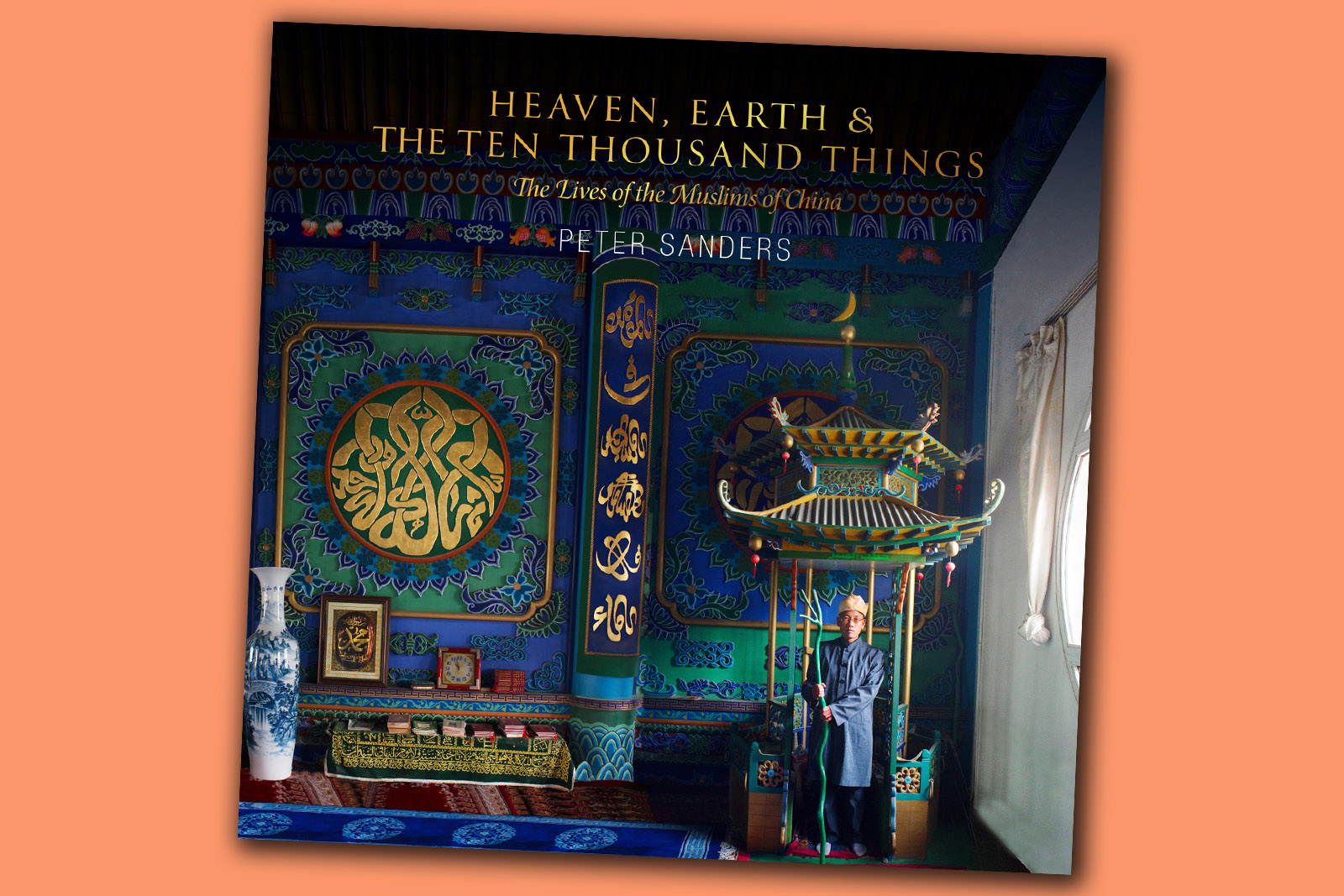

As a young child, Peter Sanders would often put a frame around objects or flowers by making a square with his fingers. “It was a way of isolating something without the distraction of all the other things around it,” says the photographer, who has spent the last five decades documenting Islamic culture around the world. Half of those years were on a project capturing China’s Muslim community, which has culminated in the new photo book Heaven, Earth, and the Ten Thousand Things.

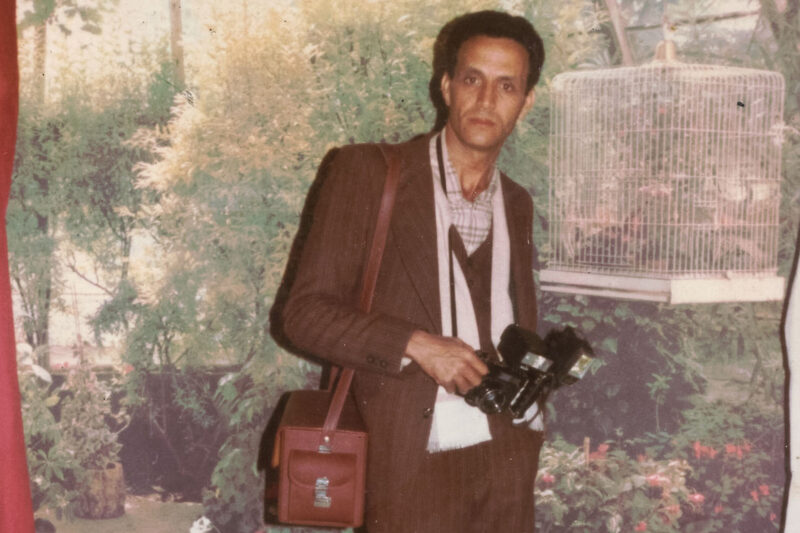

Sanders began his career in the mid-1960s as a rock’n’roll photographer in London, initially finding work through friends in the scene. He notably produced the last images of Jimi Hendrix performing live two weeks before the artist’s death in September 1970.

“In the 60s, the musicians were the poets whom we looked towards to understand what was happening in the culture and world around us,” Sanders recalls.

Towards the end of the decade, he became interested in questions of faith and spirituality, partly because he had long felt a lingering sense of anxiety and was unable to explain its roots.

“It was just in the background and it made me feel uncomfortable,” Sanders says. “As I matured as a person, I looked towards the men of knowledge, the saints and sages of the Islamic world to understand my journey through this world.”

At the time, Sanders had begun reading Paramahansa Yogananda’s Autobiography of a Yogi, the 1946 volume often credited for introducing yoga to western audiences, nurturing a desire to travel to India. He went there in 1971 with a hundred rolls of film in tow.

That initial trip would spark a 50-year-long project, Meetings with Mountains, documenting the spiritual figures he encountered across Asia, Africa and the Middle East, beginning with the Moroccan Islamic teacher and sheikh of the Sufi Darqawi order Muhammad ibn al-Habib, who Sanders photographed in the city of Meknes in 1971.

Sanders converted to Islam that year and spent the month of Ramadan in Morocco. Shortly after, in 1972, he found himself in Saudi Arabia, shuttling between the offices of government functionaries before eventually gaining permission to photograph the Hajj.

He is often cited as one of the first western photographers to cover the Hajj, following Thomas Abercrombie of National Geographic, who converted to Islam in 1964 and whose images of Mecca were published in 1966. In 1885, the Dutch orientalist Christiaan Snouck Hurgronje also photographed the city.

Sanders sold his photographs to publications around the world, including the Sunday Times, Paris Match and the Observer, offering US and European audiences what was then a rare window onto the pilgrimage.

“It was an honour to be granted this permission and to show these unique images to the western world,” he says, adding that he performed the pilgrimage simultaneously. “The Hajj is mysterious. This journey teaches you about yourself. You perform certain rituals and by God’s grace, you are changed by this.”

In 2000, Sanders travelled to China for the first time. But his interest in Muslim communities there, as well as those in the Soviet Union, went as far back as 1970. “When I heard there were Muslims in China, I just thought, ‘I want to know how they live, what their life is like’. It took me 30 years before I could actually go, when China started to open up,” he says.

Discriminatory policies against Uyghurs and other Turkic Muslims in Xinjiang were first enacted by Chinese authorities in 1949. Since 2014, a government campaign pursued with the intent of rooting out alleged “terrorism” has resulted in enforced disappearances, mass surveillance, detention in internment camps, torture, cultural and political indoctrination, as well as the demolition of religious sites and draconian restrictions on religious expression. Human rights groups have described government repression of Muslims in Xinjiang as amounting to crimes against humanity.

Sanders last visited China in 2015, and did not directly witness the subsequent effects of the government’s campaign. On one of his four visits, he traversed an expanse of almost 8,000km — from Beijing to Kashgar and back — finding communities who were “hospitable and very welcoming”. “They were happy for me to photograph them.”

The spiritual traditions that form a part of Muslim culture and practice in China resonated with the photographer. “There was something about the Chinese who had this upbringing from Buddhism to Confucianism and Taoism, which gives them a certain calmness that really spoke to me,” he says.

Included in Heaven, Earth, and the Ten Thousand Things is a poem written by the Ming emperor in praise of Muhammad, describing the prophet in Confucian terms as a “noble sage”. It expanded Sanders’s own understanding of Islam in relation to Chinese philosophy. “There’s this incredible meeting,” he says. “There wasn’t a conflict.”

The “ten thousand things” in the book’s title refers to what is considered in Chinese philosophy to describe an infinite figure. “It’s everything in the created world,” Sanders says.

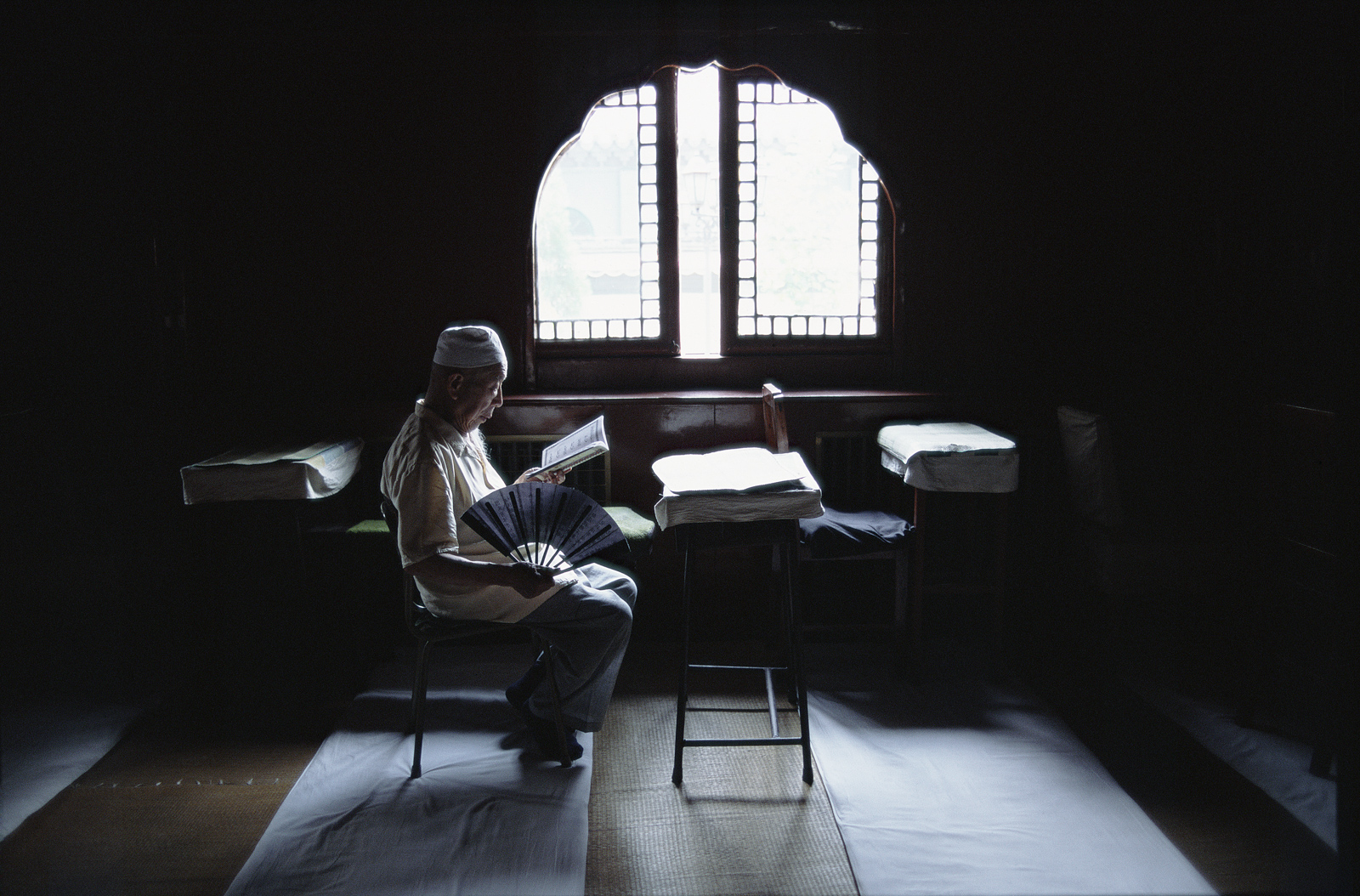

But it also, perhaps, encompasses the visual range of the project’s settings, which include a madrasa in Xi’an, where Sanders photographed a group of schoolgirls as they perform devotional songs, and the Niujie Mosque in Beijing, where a man reads the Qur’an in front of an open window that casts light through the otherwise dark interior. A scalloped arch characteristic of Islamic architecture frames the window. The mosque itself, first built in 996, blends Islamic elements with those of Han Chinese architecture.

It is precisely this aesthetic and spiritual melange inherent to the community’s practice and culture that drew Sanders to the project. The book’s cover image evokes this more overtly, depicting a mosque in the Ningxia province. The interior’s plush carpets are decorated in the patterns that one might find on Persian rugs or kilims, while what appears to be the mihrab, topped with a crescent moon, borrows from the pagoda design of Taoist or Buddhist temples.

Reflecting on his half-century-long career, Sanders says he has been given a “new lease of life” as he begins the process of archiving his work. Under the auspices of the Peter Sanders Foundation, a trust will soon be created to preserve his and other photographers’ images documenting Muslim communities, both past and future. Digitisation of Sanders’s unscanned slides is planned, while past workshops, publications and exhibitions will also be archived.

“This is our legacy and our heritage, not just the past, but present. There are a lot of young photographers documenting what’s going on in the world, and my vision is for there to be one archive,” he explains.

“None of us know how long we’ll live for, and I often feel with photographic archives, the older they get, the more important they are,” Sanders says. The effort is particularly pertinent at a moment when Islamic cultural histories are being destroyed and erased. “We need to protect it, to talk about our history and heritage before it’s all gone. It’s all being wiped out.”

Newsletter

Newsletter