Uyghur Muslims exiled in the UK dream of returning to Xinjiang

Activists call on the British government to step up measures against the Chinese state

–

Sitting in his cosy north London home, dressed in a smart blue blazer and white shirt, Kerim Zair looks content with his lot. But, within moments of meeting him, it becomes apparent that beneath the tranquil exterior lies a deep anguish.

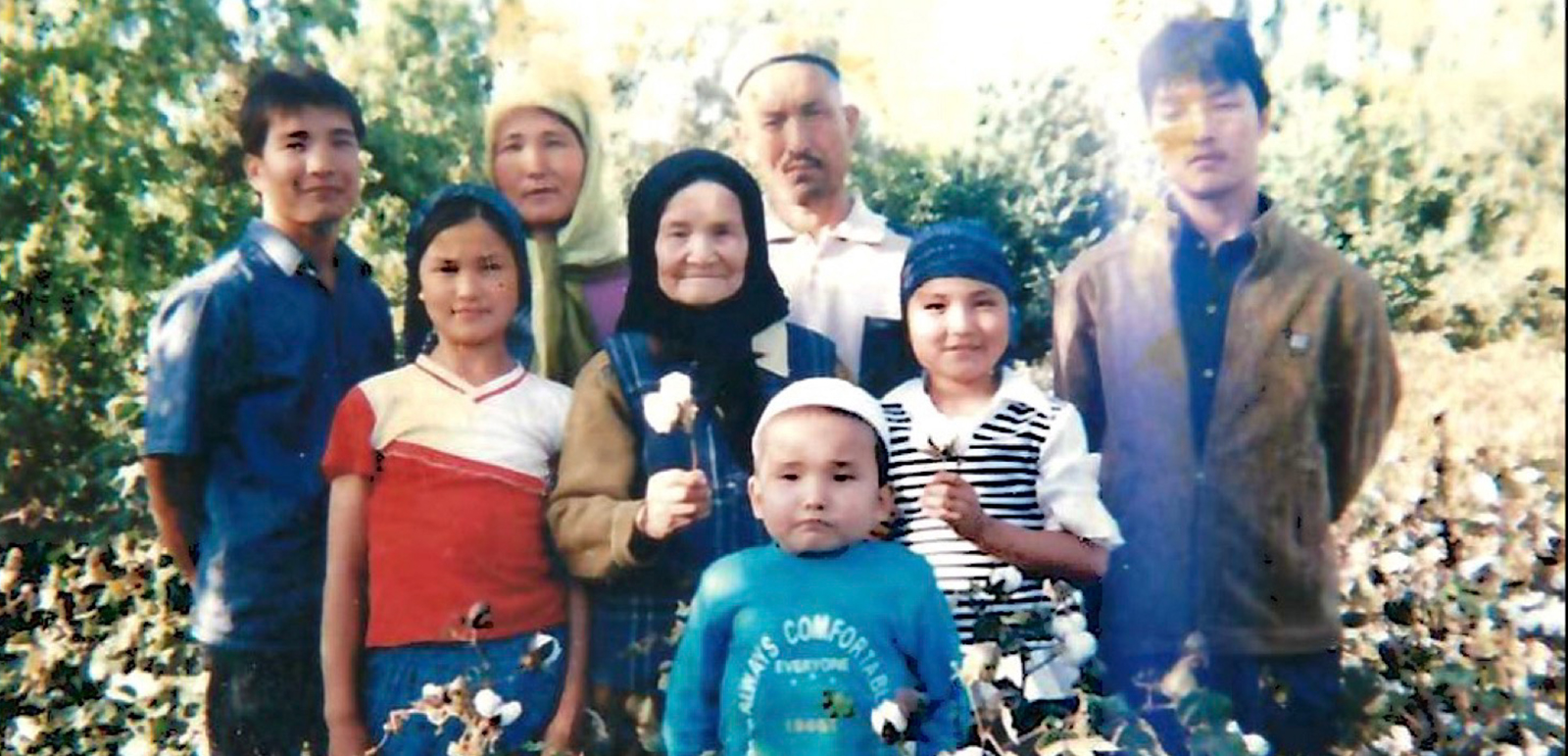

Zair, an ethnic Uyghur from China’s autonomous Xinjiang region, has not seen or heard from his mother, three brothers and two sisters since 2016. His family are among the 12 million or so mainly Muslim Uyghurs living in Xinjiang who have, according to the United Nations and leading human rights groups, suffered decades of systemic oppression by the Chinese government.

In recent years the situation has worsened under a hardline policy of “sinicisation”, implemented by President Xi Jinping and aimed at forcibly assimilating Uyghurs into the country’s mainstream culture and ideology. Zair believes some members of his family may be among the million or more Uyghurs held in Xinjiang’s notorious internment camps where, according to activists and survivors, people are tortured and pressured to leave their Muslim faith. Worse still, he fears they could be dead.

“Not knowing what has happened to my family, especially my mother, has seriously affected my physical and mental health,” Zair says through his daughter, Dilnaz, who acts as his translator. “I’m diabetic and get really stressed. Even minor things upset me. Not a day goes by when I don’t worry about them.”

Zair’s story is shared by hundreds more exiled Uyghurs living in the UK. Under threat of arrest and detention, none can return to Xinjiang and most have lost contact with their loved ones back home. Like Zair, they can’t even make a telephone call to Xinjiang, in case the line is tapped.

Zair also believes that members of his family may be being used to provide forced labour for Chinese businesses. The issue of forced Uyghur labour has become a growing concern for governments around the world. But as China’s global trading ambitions increase, activists are struggling to persuade nations increasingly reliant on Chinese imports, such as the UK, to take a decisive stand.

Rahima Mahmut is the UK director of the World Uyghur Congress, an organisation that raises awareness of the situation in Xinjiang. She is calling for a number of steps to be taken against China, including a ban on the importation of goods believed to have been produced by forced Uyghur labour.

“The mass forced labour program started in late 2018 and 2019,” she says. “We learned from some survivors that they set up factories next to the camps. Uyghurs are also transferred to other parts of China to work in factories. Basically, they are locked up, not fed properly, intimidated and made to work long hours.”

Mahmut points out that China’s forced labour program has been condemned by many politicians and NGOs, such as the Coalition to End Uyghur Forced Labour. She is now urging the UK to follow the example set by the United States, which has imposed sanctions on companies and individuals believed to be either using Uyghur slave labour or producing goods used to repress Xinjiang’s population.

“The US has blacklisted many Chinese high-tech companies,” she says. “But the UK has done almost nothing. One of our campaigns is against Chinese-made surveillance cameras and solar products. We believe they are highly tainted by forced labour.”

Zair believes that his family has been on a government watchlist since 1994, when he escaped Xinjiang. As a young Islamic scholar, he had been treated with suspicion by the Chinese authorities for some time. Then, in 1991, he was arrested, detained and tortured for six months.

“They never told me why they arrested me,” he recalls. “But, at the time, anyone who was religious was considered a suspect. While I was imprisoned, they tried to make me admit to a crime I hadn’t committed. They placed lists of false confessions in front of me and tried to make me sign them. I denied everything, so they kept beating me. They even handcuffed me and hung me up upside down.”

Zair was eventually released. Three years later and finding life in Xinjiang unbearable, he escaped to neighbouring Kyrgyzstan by bus, using a forged passport. He later moved to Kazakhstan, where he met his wife, who is also Uyghur. Eventually, with the assistance of the UN, the couple settled in Norway. They remained there, raising their four children, until 2016, when they moved to London.

Zair has been helping raise awareness about the situation in Xinjiang since he arrived in the UK, taking part in demonstrations and supporting UK-based Uyghur groups. He points to an independent tribunal, held in 2021 and chaired by Sir Geoffrey Nice KC, which reported that it was “satisfied beyond reasonable doubt” that the actions of the Chinese government constituted genocide.

An August 2023 Human Rights Watch report also describes the ongoing treatment of Uyghurs by the Chinese state as “crimes against humanity”. It adds that China has imprisoned hundreds of thousands of Uyghurs, many intellectuals and civil rights campaigners. Most recently, the prominent academic Rahile Dawut has reportedly been jailed for life for “endangering state security”, an accusation she has denied.

Rights groups cite, among other evidence, personal testimonies, satellite images and photographs as proof of the existence of the internment camps in Xinjiang.

“We know that those held in the camps face torture and sleep and food deprivation. Women are being sterilised and there is systematic gang rape,” Mahmut alleges. “People are forced to denounce their religion and they’re not allowed to speak the Uyghur language.”

Uyghurs who have not been detained are also finding it increasingly difficult to live normal lives in Xinjiang. Many are under heavy surveillance. There are also restrictions on gatherings and religious and cultural practices, as well as police raids on Uyghur households.

“Dominic Raab said the torture is on an industrial scale,” Mahmut says of a 2021 statement by the former UK foreign secretary. “But there’s been very little action. What I say to the British government is, ‘Why don’t you implement sanctions and other preventative measures to show that you support us?’”

Exiled Uyghurs live under the constant fear of falling victim to “transnational repression”, a method of policing practised by China on members of its diaspora. Studies have revealed that many Uyghurs wanting to contact their families in Xinjiang have received intimidating phone calls from police in China.

Uyghur activist and researcher Nyrola Elimä and Dr David Tobin, a lecturer in East Asian Studies at Sheffield University, have carried out extensive studies in this area.

“Our research found that the purpose of surveillance in the Uyghur community is to create paranoia so that they do not exercise their civil rights and do not share information about China and do not interact with each other,” says Tobin.

Zair believes, as the country’s largest region, Xinjiang plays a vital role in the government’s Belt and Road Initiative — a trade and infrastructure framework connecting China to many parts of the world — and therefore Xi’s policies and actions are economically motivated.

“East Turkestan is a fifth of China and we have a lot of natural resources, so it would be a big loss for the Chinese state if it lost control of it,” he says, referring to Xinjiang under the name it is known as by Uyghurs. “They say they’re hunting down terrorists, but that is just an excuse.”

While Tobin acknowledges the economic importance of Xinjiang and the fact that the repression of Uyghurs has likely created a vast pool of unpaid workers, he believes that Xi’s actions are, first and foremost, ideologically driven.

“Forced labour attracts Chinese companies and there are adverts saying cheap labour is available,” he says. “But the motivation behind these policies is not economic. The goal is sinicisation.”

While the British government has taken some steps to address the situation in Xinjiang, including imposing sanctions on a number of Chinese officials, it has yet to recognise the plight of the Uyghurs as genocide or stopped importing goods suspected of being produced by Uyghur forced labour.

In a recent meeting with his Chinese counterpart, the UK foreign secretary James Cleverly “made clear the UK’s strength of feeling about the mass incarceration of the Uyghur people in Xinjiang”. A Foreign Office spokesman also told Hyphen: “The UK government has led international efforts to hold China to account for its human rights violations in Xinjiang. We were the first country to lead a joint statement on China’s human rights record in Xinjiang at the UN.”

The Chinese Embassy in London denies all accusations levelled against Beijing about its treatment of the Uyghur people.

“The allegations so-called of ‘forced labour’ and ‘detention centres’ in Xinjiang are nothing but vicious lies concocted by anti-China forces,” it stated in an email. “Xinjiang enjoys social stability, economic prosperity, ethnic unity and religious harmony, and the human rights of the people of all ethnic groups are under full protection. Now is the best time in history for the development of Xinjiang.”

Those words are unlikely to provide much comfort to Zair, who still dreams of returning to his homeland. “One day, when I go back,” he says, “I will lie on the sand and feel the warmth of the sun on my face.”

It is a thought he holds on to when there seems to be little hope left for those he left behind.

Topics

Get the Hyphen weekly

Subscribe to Hyphen’s weekly round-up for insightful reportage, commentary and the latest arts and lifestyle coverage, from across the UK and Europe