The debate about assisted dying touches on our deepest beliefs about life

We owe it to ourselves in a democracy to fully discuss all the issues surrounding profound decisions such as when to end a life

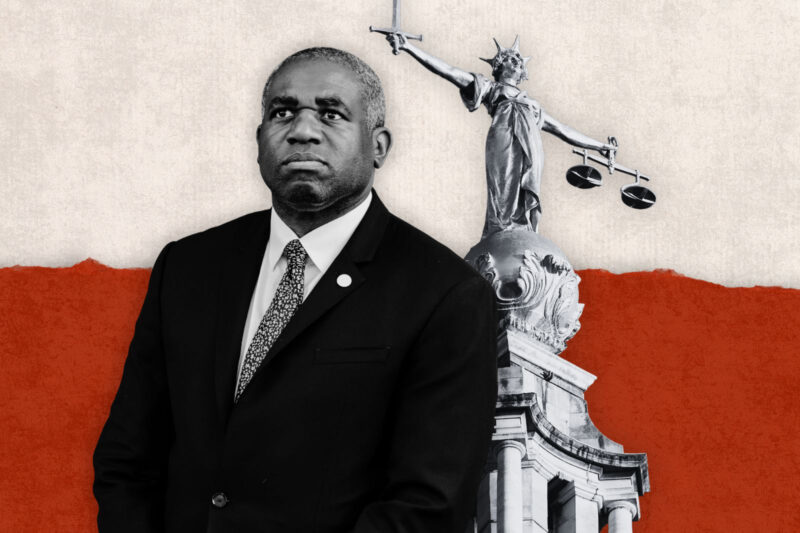

The House of Commons will vote on the second reading of the terminally ill adults (end of life) bill on Friday. Few subjects are quite as emotive, or focus on the issue of life and death quite so starkly.

Everyone involved has a powerful story to tell. Those in favour of the bill tell shocking tales of friends and relatives who have died in pain and humiliation. Listening to them is hard; living with such an illness must be excruciating. To call for assisted dying in these situations is not uncaring, let alone indifferent. It can be genuinely kind.

Those on the other side of the argument talk about how, in countries where assisted dying has been introduced, like Canada, restrictions have inexorably loosened. In 2016, the Canadian parliament passed a law allowing those whose death was “reasonably foreseeable” to seek assisted dying. Since then the law has been broadened to include those whose death was not imminent but who had a “grievous and irremediable” condition. The government has now promised to extend Medical Assistance in Dying (Maid) to those with mental illness in 2027.

These are all powerful stories, personal and political. They need to be heard. But ultimately this debate is not simply a matter of emotions or medical evidence. We can’t just add up the amount of pain in one situation and weigh it against the amount of distress in another. Nor can we calculate the amount of good done by legalising assisted dying in one country and then compare it with somewhere that has yet to pass the legislation.

The reason for this — which is also the reason why this bill, like others before it, is not government policy and why it will be a free or “conscience” vote — is that when it comes to death, we touch on the deepest source of our values and beliefs about life and human beings.

We see this in the discussion around one of the most important words in this issue: dignity. We all want to honour people’s dignity at the end of life. The critical question is — what do we mean by dignity? The term is used by all parties on different sides of the debate and, predictably, to convey different meanings.

For some, dignity means agency and autonomy. We respect people’s dignity by giving them control over their lives and the choice of how they want to end it. “All I’m asking for is that we be given the dignity of choice,” Esther Rantzen said on Radio 4 in October. “If I decide my own life is not worth living, please may I ask for help to die.” As intelligent, rational, autonomous adults, we should have the right to decide how we live and also, by implication, how we die.

For others, dignity means love and care. Humans are intrinsically relational beings, who live and move and flourish in relationships of love and trust. By this reckoning, we recognise and respect people’s dignity not simply by honouring their agency – important though this is – but by caring for them throughout their sometimes painful journeys.

Opposition to assisted dying is not, or should not be, down to any misguided valorisation of suffering, or from any determination “officiously to keep alive” people who would otherwise pass away. Rather, it is down to the belief that humans are beings whose personhood, whose very humanity, is seen and strengthened by the way we love and care for one another.

For many people, this belief in dignity-as-care, and their resulting commitment to palliative medicine, is grounded in their religious faith. It is a belief that is comprehensible to people who do not share that faith. This is a very important point, not least in the light of recent interventions that have tried to edge religious voices out of this debate. “Too much of the discussion draws on religion”, wrote Guardian columnist Simon Jenkins. “This cannot be just. Imposing religious doctrine on a largely secular country is archaic.”

As it happens, very little of the public debate has drawn on religious doctrine, most of it having been about rights of autonomous citizens, the state of palliative care, the strength of the bill’s protections, and comparisons with other legal jurisdictions. But underneath all this, there has been — there must be — an irreducible core of the debate that is about belief.

For some people, their worldview brings them to the conviction that humans are ineradicably relational beings, here to bear one another’s burdens. For others, we are made for and fulfilled by the exercise of our autonomy and freedom. Both views are defensible, whether or not they have their roots in religious or secular soil.

For me, I find dignity-as-care more persuasive than dignity-as-autonomy and I worry that if we favour the latter over the former by passing Labour MP Kim Leadbeater’s bill, we will find ourselves on a slope that inclines us, gently but inexorably, towards Canada. That belief is grounded ultimately in my Christian faith. But it is not the kind of belief that is unintelligible to those who do not share that faith, and it is not a belief that should be barred from public deliberation.

In a democracy and, in particular when discussing an issue as deep and sensitive as this, we owe it to ourselves to maintain as open and inclusive a space for debate as possible.

Newsletter

Newsletter