A death in the desert — Hajj and the fatal impact of global warming

Extreme heat contributed to the deaths of more than 1,300 people at Hajj this year, including nine British pilgrims. Aruf Rahman from Rotherham was one

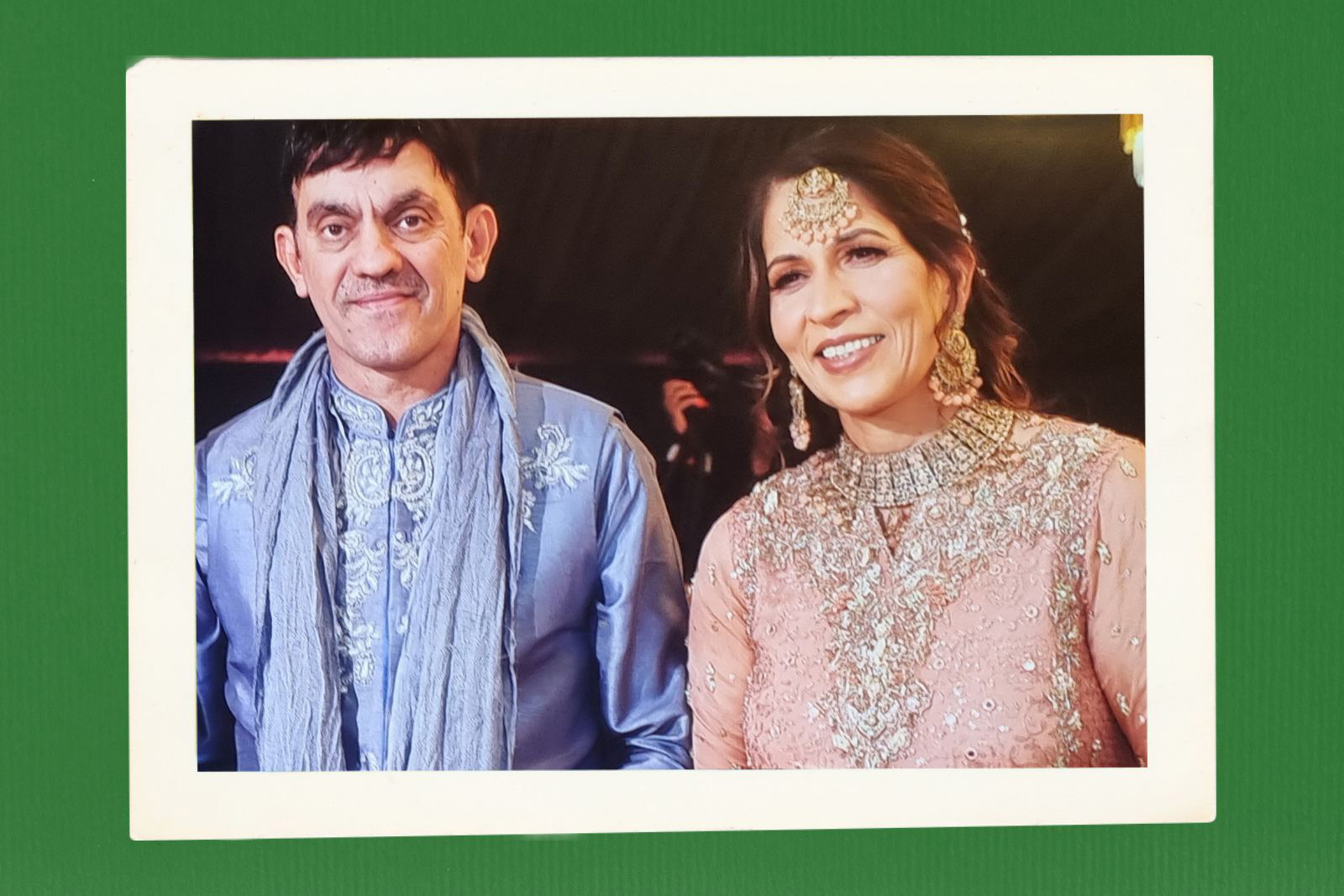

Aruf Rahman was a planner. Before every family holiday the chartered accountant from Rotherham would diligently research hotels, activities and restaurants to create a detailed itinerary for his wife Kaneez and their six children.

So when Aruf, 56, and Kaneez, 51, decided to complete Hajj, Aruf spent countless hours liaising with travel agents to create the perfect trip. In the UK, Hajj travel packages start at £7,500 per person. Although the couple spent three years scrupulously saving, after recently paying for the weddings of their two eldest children, local packages were beyond their reach.

Instead they settled on a tour organised by two agencies in Lahore, Pakistan: Al Multazam Travels and Oryx Travels and Tours. It promised four-star accommodation, two meals a day and comfortable transport throughout. Their journey would take them to Jeddah then on to Mecca, where they would spend a few days before travelling to Mina, Mount Arafat and Muzdalifah. After completing their Hajj, Aruf and Kaneez planned to visit Medina.

The trip cost them £6,200 each and was booked on the recommendation of a Rotherham-based travel agent, Habib Rehman, owner of K&H Travel, via a Hajj route that allows British people with dual nationalities to travel on their non-British passports. Pilgrims who book this way are officially registered with Saudi authorities and receive the Nusuk ID cards that verify their compliance when they arrive in Mecca.

The couple were ecstatic to finally be performing Hajj and shared the news widely. The night before their flight, dozens of their family and friends dropped by to congratulate them and pass on their prayers.

‘There is no part of the world that will be spared’

Hajj is not a single event but a series of rites undertaken across five or six days. In 2024 it was held between 14 and 19 June and drew more than 1.83 million people, including 1.6 million foreign pilgrims from 22 countries.

The exact dates are determined by the Islamic lunar calendar and in recent years have fallen at the height of the sweltering Saudi summer. While there has always been considerable risk in attending one of the world’s largest outdoor gatherings in one of its hottest countries, this year the dangers were greater still.

The summer of 2024 was the hottest on record. Scientists from Climate Central estimate that nearly 5 billion people — more than half the global population — were affected by heatwaves between 16 and 24 June, the week Hajj was held. In Mecca, where Hajj begins, the average daytime temperature was 43C. At one point, temperatures inside the Grand Mosque reached 51.8C, despite the mosque’s extensive air-conditioning.

Anticipating the scorching heat and enormous crowds, Saudi authorities issued warnings on social media and encouraged people to carry umbrellas, stay hydrated and avoid walking in the middle of the day.

There were the usual portable water stations and misting columns along the main walking routes, and this year 25,000sq metres of road around the Masjid al-Namirah in Mecca were painted with an innovative white coating that Saudi authorities said had been shown to reduce surface temperatures by up to 15C.

Yet climate experts liken such efforts to stopgap measures on a warming planet.

“We need a shift in narrative. The heat we are seeing now is unprecedented, and it requires extreme and different measures to be able to manage it and adapt to it,” said Radhika Khosla, associate professor at Oxford University’s Smith School of Enterprise and Environment. “There is no part of the world that will be spared.”

As world leaders gather in Baku, Azerbaijan for the 29th United Nations climate conference, Cop29, this week, they will be seeking consensus on how to finance and implement last year’s agreement to “transition away from fossil fuels” in an attempt to reduce global warming.

The UN’s 2024 Emissions Gap Report has warned that the world could warm by 3.1C by the end of the century if action isn’t taken immediately.

‘The heat was like walking through fire’

Problems with the Rahmans’ booking became apparent almost as soon as they landed in Saudi Arabia. While most pilgrims are allocated guides to ensure they have adequate food, water and transport, Aruf and Kaneez were left on their own.

When the couple arrived in Mina on the first day of Hajj, tour organisers assigned them to tents accommodating 40 people each, with thin mattresses tightly packed side by side. The package they paid for should have bought them comfortable foam beds in air-conditioned tents, but Kaneez claimed this wasn’t the case. “It was so hot,” she said. “There were just a few small fans, facing up to the ceiling. We were not getting any air.”

Tents in Mina are regulated by the Saudi government. In a Saudi Press Agency update shared in June, the Kingdom said the camp had been equipped with 15,000 air-conditioning units and 3,000 surveillance cameras to ensure pilgrims’ safety. Additionally, 97 medical centres employing 1,288 healthcare workers were available onsite.

The Rahmans were also left without transport. On the second day, when pilgrims travel to Mount Arafat and pray there until evening, Kaneez roamed between rows of coaches until she found a sympathetic driver who agreed to let them board.

“There were coaches on both sides of me giving off their fumes. The heat was like walking through a fire,” Kaneez said.

At sunset, pilgrims travel six miles (10km) from Mount Arafat to Muzdalifah, an open plain where they camp for the night. Again, the Rahmans hitched a ride with some kind travellers. Without a guide, the couple had not anticipated the lack of drinking water in Muzdalifah, arriving tired and dehydrated.

“It was so dark, and everything looked the same. We were worried that if we went to look for water, we would get lost,” Kaneez said. “We managed to find a sink for wudhu, and in the end we just put some of that in our water bottles and drank it.”

Beyond the survivability limit

In 2021, a study by think tank Climate Analytics examined how global warming of 1.5C or 2C could affect Muslims embarking on Hajj during summer months. Researchers estimated that the risk of heat stroke increased five times under a 1.5C warming scenario, and tenfold at 2C warmer.

Pakistan-based climate scientist Fahad Saeed, author of the study, has been examining wet-bulb temperatures – a measure of heat and humidity combined – at this year’s Hajj. When there is more humidity in the air it feels hotter because sweat doesn’t evaporate as easily, which makes it harder for the body to cool down.

Saeed’s research shows that on every day of Hajj this year the combination of heat and humidity surpassed what he calls the “survivability limit” — the point when the human body can no longer carry out basic physiological functions, such as perspiration — for six hours or more every day.

“The human body can survive very high temperatures of 50C, but with a certain amount of humidity in the atmosphere, the fatal wet-bulb temperature might be as low as 30C,” Saeed said.

Another study by the Heat and Health Research Centre at Sydney University earlier this year tested the effects of wet-bulb temperatures on human subjects, a world-first, and found the fatal point may actually be as low as 25.8C in young, healthy people, and 21.9C in older people.

As part of its Vision 2030 program Saudi Arabia wants to increase the number of Hajj pilgrims to six million a year, more than three times the current number.

“Will they be able to manage all those people, bearing in mind that we might be hitting 1.5C or 2C warming by 2050, when they are struggling to host two million at the moment?” Saeed said. “As custodians, it is the responsibility of the Saudi government to provide adequate facilities and accommodation, rather than see this as a business opportunity.”

‘I was screaming, crying, and they did nothing’

The Rahmans’ eldest son, Sohaib, 31, had just returned home from prayers on the morning of Eid al-Adha, 16 June, when his mother rang. She was crying, her voice trembling with panic. “Your dad has fainted,” she said.

Shortly after 5am that morning Kaneez and Aruf had set off on foot for Jamarat Bridge to complete the symbolic “stoning of the devil”, one of the final Hajj rites. Already exhausted from a lack of sleep the night before, they soon decided it was too hot to walk five miles (8km) in 47C heat and headed towards their tent in Mina.

“We were alone with no guide, so we kept getting lost,” said Kaneez. They arrived in Mina around midday, after more than six hours walking without water or food. After spotting a water station, they stopped for a short rest in the south of the camp.

As Kaneez sat down to regain her strength, she saw Aruf cross the road. She thought he was going to ask for directions.

Moments later, a man began waving at her. Aruf had dropped his phone and was leaning against a wall. “I hadn’t looked at his face, but I tried to give him his phone back. Then I realised his eyes were closed,” Kaneez recalled. “I started shouting and screaming, but his eyes stayed closed.”

Leaning his body against hers, Kaneez managed to lay an unconscious Aruf on the ground. “He had a backpack on, and the straps were really tight. I wanted to take it off but I couldn’t, I just wasn’t strong enough.”

Panicked and desperate, Kaneez called out to a group of police officers who were standing nearby. “It was maddening. I was begging them: ‘Please, help me pick him up, please help me get an ambulance.’ I was screaming, crying, and they did nothing.”

‘We were dealing with emergencies we were not prepared for’

Naeem Raza, from Glasgow, has been a Hajj tour leader for 22 years. He is currently affiliated with Dome Tours, a UK-based travel agency employed by Al-Bait Guests, one of Saudi Arabia’s largest Hajj operators. In 2024 he guided approximately 600 people through the pilgrimage. Raza said the intensity of the heat was unlike anything he has ever experienced. Things got even worse on the first day of Eid.

“I don’t think we have encountered so many people fainting. We were dealing with emergencies we were not prepared for, because we hadn’t expected that many people to struggle with the heat. It’s possible the Saudi government was not prepared for that either,” Raza said.

It is standard practice for the official Ministry of Transport coaches assigned to tour groups to be out of service on the first day of Eid. While pilgrims can travel by train between Mount Arafat, Muzdalifah and Mina, there is no form of transport to Mecca’s Grand Mosque. Raza’s group, alongside most other pilgrims, made the 8-10 mile (12-16km) round trip by foot. According to Saudi’s Health Ministry, more than 2,700 pilgrims were treated for heat stroke that day.

“Yes it’s safer to go by taxi, but you can be there an extra hour in the blazing heat trying to find one, so it’s a catch-22. We need official transport to prevent people from walking and dying in the heat,” Raza said.

In a press release dated 18 June, Saudi minister of health Fahd Al-Jalajel celebrated the kingdom’s “successful execution of health management efforts” during the 2024 Hajj season. He praised the 189 hospitals, health centres and mobile clinics, 370 ambulances and 40,000 healthcare staff who served more than 39,000 pilgrims.

But with just one ambulance to every 5,000 pilgrims, emergency services were “completely overwhelmed” by demand, Raza said.

“People were calling me to say my husband, or my wife, or my mother has collapsed and the ambulance is not answering the phone any more. You feel quite helpless, because they could be on the other side of town, and trying to get across Mecca on the day of Eid is impossible.”

‘The police could have told me and I would have dragged Aruf there’

While their father lay unconscious in Mina, in Rotherham Sohaib and his sister, Afsah, 24, found the emergency number for an ambulance and texted it to their mother.

“I tried the ambulance line three times,” Kaneez said. “They were just saying something in Arabic and cutting the line.”

Sohaib and Afsah then located two hospitals within a 10-minute walk of their mother and sent her the details. “Honestly, I could not see anything of the sort,” Kaneez said, adding that she sought the advice of authorities. “The police could have pointed me in the right direction, they could have told me and I would have dragged Aruf there. But they never told me anything. They just kept looking at me with a blank expression, saying, ‘I don’t know’.”

Aruf died in Kaneez’s arms at around 2.30pm on 16 June, by the side of the road where he had fainted two hours earlier. The cause of death was cardiorespiratory arrest.

He is one of 11 British nationals who died in Saudi Arabia in June 2024, according to figures from the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office obtained by Hyphen under freedom of information law. Nine of those people are believed to have died while performing Hajj.

Heat-related deaths will continue to rise without urgent action

Saudi Arabia is among the countries most vulnerable to the threats of climate change. A 2021 study by the American Meteorological Society found that since the late 1970s the kingdom has warmed at a rate 50% higher than the rest of the northern hemisphere.

As the UN Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) has established, the burning of fossil fuels such as oil, coal and natural gas is a primary cause of global warming. Fossil fuels produce around 90% of the carbon dioxide emissions that clog the atmosphere, trapping heat and making the earth warmer.

A report by global non-profit think tank InfluenceMap, published in April, found that just 57 companies were responsible for 80% of the world’s carbon emissions since 2016. The top three companies were all state-owned firms: Saudi Arabia’s Aramco, Russia’s Gazprom and Coal India.

“Many of the heat deaths we are seeing now are directly attributable to the burning of coal, oil and gas, and the companies that are producing these products bear some responsibility for these deaths,” said Sarah Biermann Becker, a senior investigator at NGO Global Witness.

According to new analysis by Global Witness shared with Hyphen, Aramco has produced enough oil and gas since 2016 to emit approximately 14bn tonnes of CO2 emissions. Using a methodology based on the mortality cost of carbon, Biermann Becker found those emissions could cause an estimated 3.2 million excess heat deaths by the end of this century.

Global Witness also examined oil and gas companies ExxonMobil, Shell, BP, Chevron and TotalEnergies, and found their combined production since 2016 could lead to 4.1 million heat-related deaths by 2100.

“The continued expansion of fossil fuel production by many of these companies poses a serious threat to human health and the planet. Unless urgent action is taken to transition to clean energy sources, the number of heat-related deaths will continue to rise,” Biermann Becker said.

Aramco did not respond to requests for comment.

‘The state did not fail’

Saudi health minister Al-Jalajel confirmed that 1,301 people died during this year’s Hajj, in a 23 June statement. Al-Jalajel said 83% of those were unregistered pilgrims who had “walked long distances under direct sunlight, without adequate shelter or comfort”.

Another senior Saudi official told AFP: “The state did not fail, but there was a misjudgement on the part of people who did not appreciate the risks.”

While unregistered pilgrims who entered Mecca during Hajj did not have access to air-conditioned facilities or transport, the Rahmans, as registered pilgrims, also found themselves without the services promised by their tour organisers.

Five months on, the Rahman family say neither the Pakistani tour operators nor Saudi authorities have accepted responsibility for Aruf’s death. Enquiries by Hyphen found that one of the Pakistani agencies, Oryx Travels and Tours, was not licensed to offer Hajj packages. The chief executive of Al Multazam Travels, Muhammad Naeem, and the manager of Oryx Travels and Tours, Tariq Dewan, both denied any wrongdoing when approached by Hyphen.

Hyphen approached Pakistan’s Ministry of Religious Affairs and Interfaith Harmony for comment.

“I know my husband won’t be coming back,” Kaneez said. “The only thing we can do is protect anybody else who goes there, because this will happen again until someone is held accountable, there’s no doubt.”

‘Adaptation is not going to be enough’

As extreme heat events become more common, climate experts say outdoor events will need to change. Lea Ranalder is associate programme management officer, human settlements for UN-Habitat, an agency that works to make cities more sustainable. She urged organisers to prioritise access to water, as Paris did during the 2024 Olympic Games.

“During the Olympic Games, there was a big call to bring water bottles and drinking water was provided free of charge at all venues,” Ranalder said. “In many public events it is very expensive to buy water, and there’s often long queues. If there isn’t quick, easy access then people won’t drink it because it’s just too much hassle.”

After more than 700 people died during a heatwave in Paris in 2003, city officials implemented a campaign to encourage people to carry water bottles with them. “You can walk into any restaurant, give them your bottle and they will refill it free of charge,” Ranalder said.

Though Saudi authorities supply free drinking water at many key sites, Kaneez said she and Aruf were unable to find water in Muzdalifah or along the route they walked on Eid, 16 June.

Hajj guide Raza also claimed that on this day authorities switched off water fountains inside the tunnels to the Grand Mosque of Mecca.

“They did that from a safety point of view, because otherwise people congregate in that area. They sit down and it becomes congested,” Raza said. “But it meant it took people an extra half an hour or more to get to a water point.” He added that some pilgrims were reluctant to drink too much water as toilet facilities weren’t readily available.

Climate experts interviewed by Hyphen pointed to an often overlooked yet sustainable and effective way to lower temperatures: planting trees. In Australia, researchers compared the surface temperature of two parallel roads in Sydney, one lined with trees, the other not. They found the shaded road was 20C degrees cooler than the one without trees.

The Saudi Green Initiative aims to grow 10bn trees across the kingdom over the coming decades. The Climate Action Tracker, an independent project that tracks governments’ climate efforts, has called the target “unrealistic”. As of 2023, Saudi Arabia said it had planted just 43.9m trees, 1.3m of which are in Mecca. Some of these are dotted around the tents that pilgrims stay in near Mount Arafat.

“Yes, we need better provisions for shading, ventilation, hydration and cooling, but at some point our adaptation measures are just not going to be enough,” said Khosla. “We need to focus on mitigation and combat climate change or we will continue to see temperatures rise.”

Saudi Arabia’s Crown Prince Mohammed Bin Salman is scheduled to speak at Cop29 on 12 November.

‘Our dad was a loving, caring family man’

Aruf lived a full life. He was known to offer free accounting services to anyone who needed them and often organised walks with his neighbours. He never ate at home on Fridays — the evening was always reserved for dinner out with friends.

He loved football and was a Manchester United season ticket holder. By the time Sohaib’s son was one, Aruf had already given the little boy four club kits, in the hope his grandson would share his passion for the sport.

Six weeks after Aruf died, I visited the Rahmans at their family home, a smart, semi-detached house on a tree-lined street in Rotherham. Aruf’s grandson ran into the living room, kicking a small football.

They are a large, close-knit family that includes three children Aruf and Kaneez adopted after the death of Kaneez’s younger sister in 2010. The walls are decorated with graduation portraits and photographs from family holidays, Aruf smiling proudly in all of them.

“Our dad was a loving, caring family man. He was always putting others first,” Sohaib said. “When my grandma would thank him for adopting and raising my aunt’s children, he would say: ‘No, she wasn’t just Kaneez’s sister, she was my sister as well, and these are my kids too.’”

When Kaneez arrived home from Saudi Arabia she learned that in his final moments of consciousness Aruf had been trying to video call their youngest son, Hamad. “He said he could only see dad’s blurry face and then the phone dropped.”

Hyphen has contacted Saudi Arabia’s Ministry of Hajj and Umrah for comment.

Newsletter

Newsletter