Black renters twice as likely to face homelessness because of a ‘no fault’ eviction

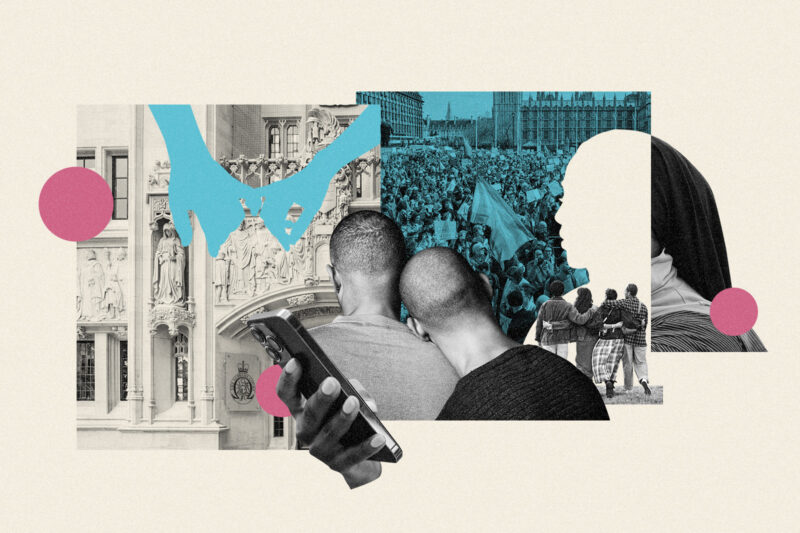

Despite making up only 4% of private renters in England and Wales, Black households account for nearly 10% of those threatened with homelessness after receiving a section 21 notice

Black families in England are more than twice as likely to face homelessness due to a “no fault” eviction, Hyphen can reveal.

According to data obtained by Hyphen under freedom of information law, during the first quarter of 2024, Black renters made up 9.8% of the 6,630 total households threatened with homelessness after receiving a section 21 notice — where a landlord can evict a tenant for no reason — despite only making up 4% of private renting households in England and Wales. Black households made up 9.9% of total section 21 recipients since 2021, the data showed, making them more likely to face homelessness as the result of a section 21 notice than white, Asian, mixed or “other” households.

The data also revealed that the total number of section 21 recipients assessed by local councils as being owed a so-called homelessness prevention duty — that is, being at risk of homelessness without council intervention — has risen from 2,640 in the first quarter of 2021 to 6,630 in the first quarter of 2024. In all, 73,129 households have faced possible homelessness because of “no fault” eviction notices since 2021, including 11,250 Asian families, or 7.8% of the total.

This is despite a pledge in April 2019 by the then Conservative government to end section 21 evictions altogether.

Sylvia Johnstone, a mother of two teenage children, has been served a “no fault” eviction notice requiring her to leave her home in Bushey, Hertfordshire by 31 October — despite having taken on a second job to cover a £350 monthly rent hike and soaring energy bills. She told Hyphen the eviction had turned their lives upside down, and she had been unable to find a new home to rent.

“Both my kids asked me the same question separately: ‘Mum, do you know where we’re going yet?’ and I just haven’t got the answer,” she said.

Johnstone added: “I’m being made to feel like I’m squatting in someone else’s house. I’m still paying my rent, I’m still looking after the house like I have been, but it’s got a different feel now. I’ve been told we have to pack everything up and get it out of the house before the bailiffs come.

“The system is so flawed. I could understand if I was months and months in arrears and if I was a bad tenant, but this isn’t my fault.”

Gill Taylor, strategic lead of the Dying Homeless Project at the Museum of Homelessness, said section 21 notices “rip people out of the communities that they’re part of and force them into other places, largely to enable landlords to increase profits in gentrifying neighbourhoods”.

She added: “For people of colour, that can have very specific effects on their safety, on their mental health, and so on. So it’s not just about housing, but all of the things that homelessness and risk of homelessness can lead to.”

Another woman, who has asked not to be named, was evicted from her home in north London in 2021 using a section 21 notice and is still living in temporary accommodation with her children three years later. “I can see how this would push anyone to the edge because it is just relentless,” she said.

She described feeling caught between a landlord, who did not want her in their home, and her local council, who she felt did not want the responsibility of finding her homeless accommodation.

“It’s dehumanising and it takes a toll on your mental health because there’s no peace.”

She continued: “To get back on your feet afterwards is so difficult because when you live somewhere for a number of years, you’re going to have quite a collection of things, whether that’s furniture or even memories. And the local authority doesn’t provide a service where you can put your things and normally you’re dealing with some of the most vulnerable people. So you have them literally outside on the street with a lifetime worth of valuables and memories. It’s very undignified.”

Taylor said people of colour may be less able to challenge eviction notices, citing language barriers, immigration restrictions and a lack of knowledge about the rights they do have.

She added: “The people we see who are most at risk of being evicted in this way are also living at the intersection of other forms of exclusion, injustice and poverty.”

Polly Neate, chief executive of Shelter, said: “It’s shameful that racial inequality and discrimination continue to thrive across private renting. No-fault evictions are a leading cause of homelessness, and Black renters are being disproportionately impacted.

“Decades of failure to build enough genuinely affordable social homes have caused private renting to balloon, while regulation hasn’t kept pace, forcing many renters to jump through hoops to find a home. Black renters, who are statistically more likely to receive benefits, are being regularly subjected to discriminatory practices like ‘no DSS’, excessive affordability checks and demands for large sums of rent up front.”

Another woman, who has also asked not to be named while she challenges her landlord, said the stress caused by the looming threat of eviction has changed her. “I feel like I can’t do anything in my home. It’s not like before. I’ve packed all my stuff in my living room in my flat. I keep saying, maybe it’s today, maybe tomorrow, I just don’t know. I’m not like how I was before.”

The renters’ rights bill was announced in Labour’s first king’s speech in July. Along with banning section 21 notices, the bill seeks to introduce policies such as limiting rent increases and extending Awaab’s Law — a requirement for social housing landlords to inspect and repair hazards within a strict time limit — to the private sector.

A spokesperson for the Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government said: “To end homelessness for good we must tackle the root causes of it. We have established a new dedicated inter-ministerial group, chaired by the deputy prime minister, to develop a long-term strategy working with mayors and councils across the country.”

But Taylor believes that the government needs to do more to tackle homelessness. “The temporary accommodation crisis that local authorities are experiencing, the squalid conditions that people are being forced to live in, deaths on our streets and the billions in profit being leached from the universal need we all have for a safe home — these issues won’t be resolved by banning the section 21 notices,” she said.

“At the root of it, the government should commit to building social housing at the scale needed to ensure lifetime homes for everyone.”

If you’ve got a housing story you’d like us to consider covering, please email our reporter Anita on anita.mureithi@hyphenonline.com.

Editor’s note: An earlier version of this article stated that 73,129 households had been served with section 21 evictions since 2021. In fact, this is the number of households that had been assessed as facing homelessness — that is, assessed as being owed a homelessness prevention duty — by councils following receipt of a section 21 eviction notice during that time period.

Newsletter

Newsletter