Most Muslim doctors oppose assisted dying, survey suggests

More than 8 in 10 healthcare workers tell British Islamic Medical Association they disagree with legalising euthanasia, on ethical, practical and religious grounds

Most Muslim medical professionals in the UK believe doctors should not be able to prescribe or administer life ending medication, a new survey suggests.

The British Islamic Medical Association (Bima), which represents Muslim medical professionals across the UK, surveyed 88 healthcare workers between July and August in response to a Scottish government consultation on assisted dying for terminally ill adults. Parliament is expected to debate its own bill on assisted dying in England and Wales next week, with MPs to be given a free vote.

Of those surveyed, 88% of healthcare workers disagreed that it should be legal for doctors to prescribe life-ending medication. Around 6% of respondents said doctors should be allowed to prescribe the medication, while another 6% were unsure.

On whether doctors should have the legal right to administer life-ending medication, 90% disagreed. Around 6% agreed, while the rest were unsure.

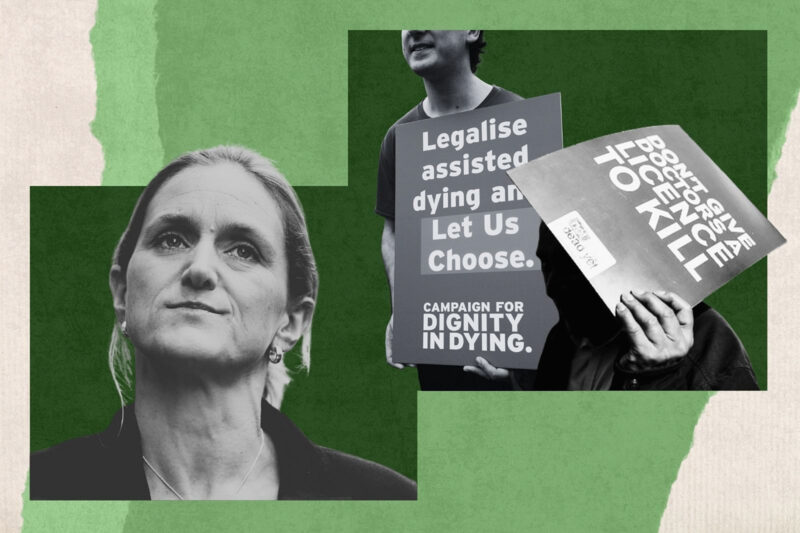

Backbench Labour MP Kim Leadbeater will introduce a private member’s bill on legalising assisted dying to parliament on 16 October. Writing in the Guardian, Leadbeater said her bill would give people “the comfort of knowing they have a choice over what happens to them”.

The bill has been welcomed by assisted dying campaign groups, such as Dignity in Dying, which says it will give people control over how they die and will guarantee a “safe and peaceful death”.

Other groups have expressed concerns about how it could affect vulnerable people. Care Not Killing, a group that opposes euthanasia and assisted suicide, urged the government to “fix our broken palliative care system” rather than discussing a “dangerous and ideological policy”.

Nadia Khan, a palliative medicine consultant from the West Midlands and the end of life group lead at Bima, said doctors who took part in the survey had expressed concerns about both the practical and ethical issues they may face if the law changes.

“The key concerns we have centre around safety,” said Khan. “There’s a risk of assisted dying being misused, where people from ethnic minority groups may not be able to access information. Vulnerable groups may end up either being coerced into taking up assisted dying, or feeling like they have no other choice because of the gaps around good end of life care and social support.

“At the moment, we haven’t got equitable end of life healthcare for everyone. That needs to be resolved. Assisted dying is the wrong answer to the right question, which is how do we make people more comfortable at the end of life?”

Some healthcare workers surveyed by the association expressed support for the change in legislation. One medic commented: “People with terminal illness should be able to choose. They have the right to live as they choose and die if chosen.”

Another said: “Quality of care with patient choice is key but we have too long focused on prolonging life by any means possible which is not always in the best interest of patients.”

MPs previously voted against a bill on the issue of assisted dying in 2015. In a letter published in the Observer at the time, faith leaders said the bill would “put at risk many more vulnerable people than it seeks to help”. It was signed by Justin Welby, the archbishop of Canterbury, as well as chief rabbi Ephraim Mirvis, the Muslim Council of Britain and the Network of Sikh Organisations UK.

Khan said some professionals had also raised concerns about how the proposed bill could compromise patient-doctor relationships. “When it comes to patients and healthcare professionals, there is an underlying agreement of trust that we will do no harm, that we are there to help them and heal them. That risks being undermined quite significantly,” she said.

Some of the doctors surveyed said they objected to the bill due to their religious beliefs, with Islam emphasising the sanctity of life. One doctor commented: “As a Muslim, I am duty bound to not get involved in assisted dying.”

But 77% said that, even setting aside their religious views, they still had ethical and practical concerns about assisted dying.

Another doctor said: “This will undoubtedly open the door to the silent suggestion to many disabled people by their often strained families, disabled patients who may already feel a burden and are far more likely to suffer isolation, depression and suicidal thoughts. This cannot be allowed to pass.”

Newsletter

Newsletter