The greatest games on earth — and in space

Held in the futuristic city of Astana, Kazakhstan, the fifth World Nomad Games were a celebration of ancient sports — with some notable allowances for modern life

This year, there would be no goat. Traditionally, ahead of a game of kokpar — Kazakhstan’s national sport — a decapitated goat carcass is soaked in cold water for 24 hours to toughen it up. The dead animal is used as the “ball” over which two teams of horse riders compete, fending off the opposition as they reach down from their mounts to grasp the slain animal and attempt to keep hold of it until they reach the kazan, or goal. The team that gets the most goals by the end of the 40-minute match wins.

To the unaccustomed, this traditional sport can appear wild, unusual, barbaric — and concerns for their image led Kazakhstan to decide, 10 years ago, to professionalise their national game by substituting a slaughtered goat for a dummy. At this year’s World Nomad Games, held in Astana from 8-13 September, organisers decided that a specially designed goat-moulage would also be used for kok boru, the variant played by neighbouring Kyrgyzstan. The Kyrgyz team were not pleased with the decision.

Kokpar and kok boru were two of the most highly anticipated sports at the Games, founded in 2014 as a sort of Olympics for nomads. Traditional sports, mainly from the nomadic peoples of central Asia, are showcased across a variety of disciplines, including horseback archery, tug of war, strongman competition Powerful Nomad, hunting with eagles; and an exciting display of horsemanship, tenge ilu, whereby riders gallop along a track lined with small sacks of coins and attempt to grab as many as they can while hanging from the side of their horse.

Astana is something of a strange place to host a festival of ancient sports. Since it was made the capital of Kazakhstan in 1997, developers appear to have been busy ensuring that each building comes with its own superlative, to hammer home its aggressive modernity. The city boasts the largest spherical building in the world; the largest mosque in central Asia, with 63m-tall minarets intended to reflect the prophet’s age at the time of his death; the largest tented building in the world, the Khan Shatyr, or “king of the tents”, designed by British architect Norman Foster; the Alua Ice Palace speed skating venue; a velodrome shaped like a bicycle helmet; and an enormous complex shaped like a waving flag that claims to be both the “largest” and “youngest” museum in central Asia.

More than 2,500 athletes from 92 countries, including Russia and Mongolia but also the UK, Togo and Central African Republic, were brought to Kazakhstan to compete in the World Nomad Games. Shuttle buses ferried them from their hotels to one of several sci-fi sports arenas. The intellectual games had their own venue: row upon row of gaming tables were set up for ancient strategic board games like mancala and oware at the 18-floor Duman hotel complex, where glass-panelled lifts carried athletes up and down from their hotel rooms to the gaming halls. This was where Seth Bonti-Asamoah, a member of the UK team from Tooting, south London, was competing in togyzkumalak, one of the oldest board games in the world.

Bonti-Asamoah grew up playing oware, another game in the mancala family, where players attempt to distribute small stones across holes in a board to capture their opponents’ pieces. He still organises oware tournaments, but since 2010 he has also competed in the Kazakh variant, togyzkumalak. His passion has taken him all over the world, from Spain to central Asia. This was his second World Nomad Games; he also competed at the 2018 games in Kyrgyzstan. He was now visiting Kazakhstan to play competitive togyzkumalak for the fourth time.

“They’re very keen on promoting the game,” he explained. “It’s interesting, these games are played all over the world. From China all the way to the Caribbean and even in South America. I think it’s this traditional aspect of the game that unites people.”

On day two of the games the organisers issued a press release concerning togyzkumalak. “As part of the support for the fifth World Nomad Games,” they announced, “the ancient intellectual game of nomads has reached the stratosphere. This Kazakh strategic game was lifted to an altitude of 28,324 metres. During the flight, the temperature reached -55°C.”

There might be no better symbol for the modern repackaging of ancient sports: Kazakhstan had launched a togyzkumalak board into space.

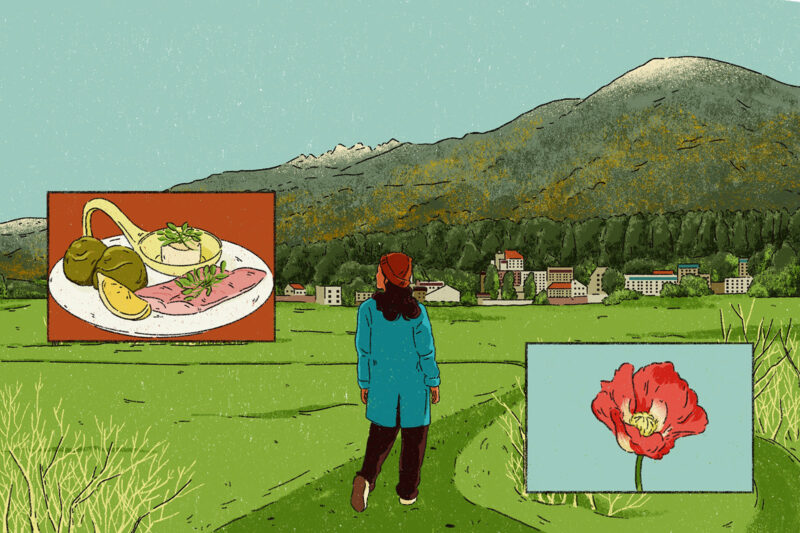

The equestrian sports were held at the edge of Astana where, after all its showing off, the city finally gives up and returns to steppe. Two venues played host to competitions on horseback: the hippodrome and the Ethno-aul (“ethnic village”), a specially built village of yurts showcasing the traditions of different regions of Kazakhstan. Here, visitors could take a break from watching horseback archery and head over to yurts selling food and refreshments, choosing from plov (pilau rice with carrots and meat) or kuyrdak (a dish made from stewed horse meat, with onions and potatoes) – or stop by the Costa Coffee or Papa John’s yurts. Incredibly tall Kazakh men wearing suits of armour wandered about posing for photos; troupes of performers sang traditional songs; golden eagles and Tazy hunting dogs stared out at the crowds.

The animals were real, the charcoal ovens cooking horse-meat were real, but the yurts rested on astroturf, electrical cables ran underneath: the entire interior of one tent was lined with an HD digital screen, playing a short film promoting Kazakh tourism on a loop.

I met Alima Bissenova immediately after the kokpar final, as the crowds were streaming out of the hippodrome. After finishing 4-4, the game had been clinched by Kazakhstan in sudden-death extra-time — but the match had been controversial. There was a 20-minute stoppage in play when, with the score 3-1 to Kyrgyzstan, a Kazakh player had deliberately whipped a member of the opposing team. The Kyrgyz team had threatened to leave the field altogether. The next day, they would refuse to wear their silver medals.

Bissenova is associate professor at the Department of Sociology and Anthropology of Nazarbayev University, but she also presents a programme on Kazakh TV called Cultural Contexts and has written about Kazakhstan’s attempts to stake out a unique identity on the world stage. I asked her about the authenticity of the World Nomad Games.

“It’s difficult to measure authenticity, right? It’s like, how do you measure the sincerity of somebody? But it should be pointed out that the number of horses in the country is growing dramatically. So, there are objective reasons for a renewed interest in herding, horsemanship, crafts. During Soviet times, the Kazakh identities of Islam and nomadism were forced to the fringes. Now, they’re back in the centre.”

Given that we had just watched the final, I asked about kokpar and the dummy goat. Was anything lost in the updating of these traditions?

“I don’t play the game myself,” Bissenova said, “but my programme on television tonight is about the game, so I can give you the view of the guys who do play it. They say that this dummy goat is much more traumatic for the body. With a real goat, there is flexibility if it gets caught between you and another horse. The dummy is harder. It’s much more dangerous.

People who think killing a goat for sport is “just barbaric” misunderstand that after a game of kokpar the animal is cooked and eaten, she added. “There is a ritual to it. It’s not just waste. I can also tell you in the real games in the countryside – away from the championships – no one plays with a dummy. Never.”

The closing ceremony was held at the Ethno-aul, and featured a surprise announcement: the sixth World Nomad Games will be held where they began, in the mountains of Kyrgyzstan. Given that country’s objections to their neighbour’s modernisations, this will presumably mean a return to tradition. The goat will likely be back. As for the Kazakh games: the carcass may have been a fake, but the passions were very real.

Newsletter

Newsletter