Parwana Fayyaz Q&A: ‘Each Afghan woman is creating a history, but silently’

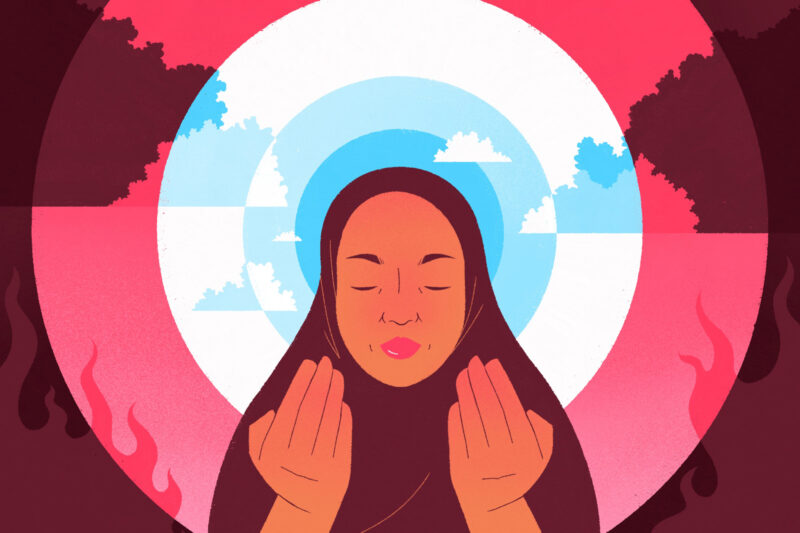

Afghan scholar and poet Dr Parwana Fayyaz explores the meaning of home, family and connection within an Afghan context. Photo by Dr Luca Zenobi

The poet on Persian storytelling, refugee identity and the importance of women’s voices

Dr Parwana Fayyaz was just seven when her family fled Afghanistan for Pakistan during the Afghan Civil War. Upon her return to Kabul almost a decade later, the writer recalls cherished reunions with extended family but, even so, the experience of being a child refugee stayed with her. Though she has not lived in Afghanistan since she was 19, her heritage continues to inform her work as a scholar and poet.

Fayyaz, 34, went on to study in Bangladesh, at Stanford University and, most recently, at the University of Cambridge, where she completed a PhD in Persian Studies and is now based. Inspired by the oral traditions within Persian storytelling, Fayyaz uses her words to make sense of her own identity, as well as explore the meaning of home, family and human connection within an Afghan context.

She published her first collection of poetry, Forty Names, in 2021, and is currently working on a second book. She also worked as a translator on the new anthology My Dear Kabul, a collective diary by 21 women tracing their experiences after the city’s fall to the Taliban in August 2021. The anthology was compiled by Untold Narratives, a writer development programme for marginalised writers.

Fayyaz spoke to Hyphen about her love of Persian literature, her work with Untold Narratives and amplifying Afghan women’s stories.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Can you describe some of your earliest memories of Afghanistan?

It was the night we left Kabul. We were sleeping. My father came into the room, picked us up and took us outside. Then we were on a bus. It was a very rough journey. I still remember how shaky it was, and my dad telling us the classic tale of Buz-e-Chini, the Chinese goat who has to fight the wolf to protect her three children.

In 2005, my father found a job in Afghanistan and decided to bring us back to Kabul permanently. The first thing I noticed upon entering the city was the mountains. I remember looking at them and feeling deep down that I knew those mountains.

What made you start writing and how has poetry helped make sense of your personal experience?

While I was studying for my BA at Stanford, I remember my literature teacher saying: “Read a poem, write a poem”. That inspired me to think, I can write a poem. So I wrote about my mother. I had dreamed she was standing outside a burning room, calling me to open the door. As the eldest daughter, I felt a sense of guilt when I left home, so I wanted to somehow honour her. I remember I read the poem to the class, and everyone cried.

My teacher was very happy and she encouraged me to write more. She saw that I was very sensitive with words, in the way I think and feel. I’ve done fiction and memoir, but poetry is a very powerful tool, especially when it involves memory, because memories are fragments. They can never be whole. For people like me — refugees and the displaced — there is this sudden detachment from the past and homeland. But poetry makes it possible to feel connected again.

What is it that interests you most, as a scholar of literature, about the Persian storytelling tradition?

Ancient Persia was always trading, exchanging stories, welcoming philosophers and thinkers. Persian literature is a melting pot between the distinctions of east and west. It enables storytellers to meet and learn from each other.

We also have a history of brave women, starting with the 10th-century writer Rabia Balkhi. She was brave enough to tell her story and to share her feelings through her poems. In the end the world went against her but, even so, nothing could silence her voice. It lives on through us and the poetry itself.

How did you first hear about Untold Narratives, and what has been your highlight from working with Afghan female writers?

It was early 2020. I got an email from Lucy Hannah, the director, saying that she’d heard about my work and wanted me to be involved with interpretation, so my role was providing a bridge between the Afghan writers and English speakers. I immediately said yes.

Untold take their writers so seriously. I don’t think we’ve ever had this type of platform before. I remember when the first book came out, My Pen Is the Wing of a Bird, Lucy shared that she wanted to make a network of Afghan writers. I said I would love to be a part of it because this is what we have been missing for a very long time, for us to tell our stories on a global scale. And that’s what Untold is doing, bringing those stories to a global audience.

It’s been an honour to work with and get to know the writers. They’re so full of life. I was last in Kabul in 2018. The part of me that was missing Afghanistan — these writers managed to fill it with their stories. This was a way home for me.

Your own book, Forty Names, also focuses on the stories of Afghan women. What do you hope people take away from the collection?

I’d been working on Forty Names for more than 10 years. Some of the poems were that old. I had a very strange feeling about the book after the fall of Kabul, like I had to hide it away because of the women named. But those same women were happy to be mentioned.

The book tries to bring context to what is happening in Afghanistan. We know things are not looking as great as they should be, but every woman has a story. It’s sad when people say Afghan women are victims — the world shouldn’t try to define them. Every woman is resilient in her own way. We should share their stories without trying to overemphasise certain things.

Yes, we are seeing women less on the streets. They are not in the public eye, but they are there. You just have to look for them. We don’t know what’s happening behind closed doors; each Afghan woman is creating a history, but silently.

My Dear Kabul: A Year in the Life of An Afghan Women’s Writing Group, published by Coronet, is out now.

Newsletter

Newsletter