Far-right violence against small UK Muslim communities sets a worrying precedent for all minorities

The past shows that racism can only be defeated when we all stand together against it

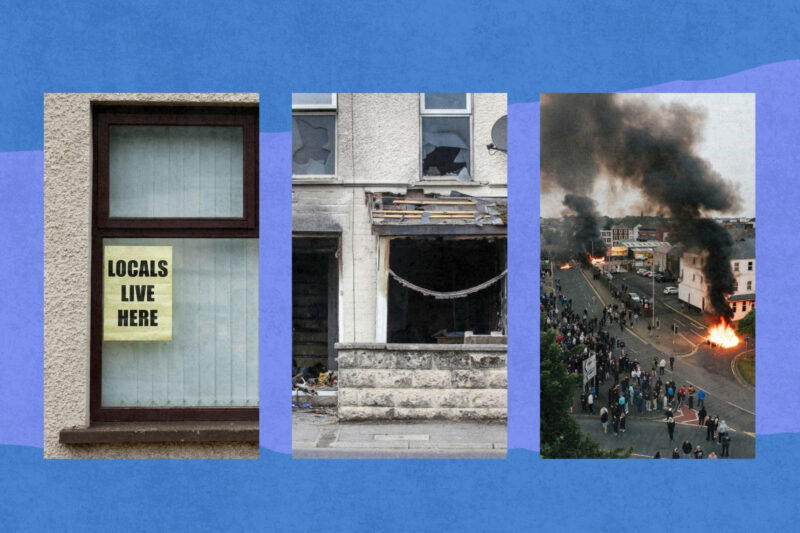

A young South Asian man is walking alone down a normal-looking English street. Suddenly, he is punched hard in the face. Onlookers cheer, laugh and yell racial slurs. “A Paki got banged,” one shouts as those around him begin to smash the windows of small businesses and kick down the front door of a house. The day before, similar scenes occurred elsewhere. In headline-grabbing riots, a mosque was bricked and the garden walls of nearby homes were torn down and turned into missiles to throw at police and local residents.

These are not stories from the 1970s. They are all-too-recent events in Hartlepool, County Durham, and Merseyside. The last week of July 2024 will be remembered for the fatal stabbings of three young girls in Southport and the days of violent unrest that have followed. Fuelled by online misinformation about the identity of the suspect — now confirmed to not be Muslim — Muslim communities have been blamed, harassed and assaulted, and mosques across the country have been threatened.

Emboldened by social media provocateurs, sections of the conservative media and a number of political figures, including Reform UK leader Nigel Farage, the far right has gone on the rampage. Now, there are reports of further rallies being planned in Liverpool, Middlesbrough, Bristol, Belfast and Hull, with some organisers reportedly urging protesters to congregate outside Muslim places of worship.

The worst effects so far have been felt in northern towns with small Muslim communities. This represents a dangerous shift in strategy from the far-right, whose supporters have usually rallied in large metropolitan cities. The targeting of small towns serves a joint purpose for racist groups. First, it allows the movement to appear much larger and stronger than it really is, especially when outside agitators are brought in to bolster numbers.

Second, by successfully intimidating whole communities, it emboldens supporters and sets a precedent for larger-scale or more random attacks elsewhere. As a result, it is not only Muslims in those communities who are increasingly vulnerable, but minorities everywhere. The South Asian man in Hartlepool, for instance, was not asked what he believed before he was assaulted.

As a nation and a community, we have seen similar scenes before. Many of the streets in my hometown of Luton, Bedfordshire, were once no-go areas for my father’s generation. Back in the 1970s and 1980s, local racist street gangs routinely sought to terrorise people of colour.

Then, as now, racist violence did not occur in a vacuum. Front-page headlines about an “invasion” of immigrants and inflammatory rhetoric from mainstream politicians such as then prime minister Margaret Thatcher, who warned that the UK might be “swamped by people with a different culture”, combined to create a toxic atmosphere in which far-right groups such as the National Front (NF) and the British National Party (BNP) flourished.

The parallels with today are glaringly obvious. Ever since hundreds of thousands of peaceful protestors — Muslim, those of other faiths and none — began to march in solidarity with the people of Gaza, a panic has been whipped up about “Islamists” taking over the UK. Former home secretary Suella Braverman led the charge, labelling peaceful protesters “hate marchers” in late October. Former Tory MP Lee Anderson then added that London Mayor Sadiq Khan was “controlled by Islamists”. More recently, Reform leader Nigel Farage stated that British Muslims “do not subscribe to British values”.

Even Labour figures have contributed to that narrative, making wild generalisations about peaceful protesters and those who chose to support independent candidates in the recent general election.

Instead of engaging directly with UK Muslims and listening to their concerns, much news coverage has, instead, implied that the community is only interested in events overseas. That narrative of split loyalties and incompatible difference has, naturally, been seized upon by the far right. In November 2023, there was a reported 600% increase in Islamophobic hate crime. And yet, our politicians appear reluctant to acknowledge that Islamophobia is a real thing, let alone commit to tackling it.

In Luton, people of my father’s age know the effect rising prejudice can have. It was because of their efforts in the fight against racism that my generation was in a position to take a more assertive stance. Despite our town being the home of the anti-Muslim English Defence League (EDL), there were enough of us — regardless of ethnicity or creed — ready to combat the threat of racism.

Now, people who live in places with similarly sizable Muslim communities — Bradford, Birmingham, east London — generally feel relatively safe. That sense of comfort can, however, breed complacency. Those most anxious about a rising far right reside in areas with much smaller Muslim communities. Muslims make up just 1.3% of Hartlepool’s population according to the 2021 census. One young man from the town reached out to me via Twitter during the riots.

“Most of the community held their ground well by just staying in groups at the end of our streets,” he said. “It’s a worrying time to be a person of colour in this town at the moment.”

The histories of the NF, the BNP and the EDL all show that the far right has been beaten when communities have come together against it. While such groups purport to speak on behalf of the white working class, they have been firmly rejected by those exact people time and time again. Now, in an age of more diffuse online rhetoric, we must stand together in the same way.

In Liverpool, the far right is set to target the oldest place of Muslim worship in Britain — the Abdullah Quilliam mosque, established by a British convert to Islam in 1889 — on Friday August 2. Imam Adam Kelwick, has responded by offering free food and drink and peaceful dialogue inside the mosque. In Hartlepool, more than £10,000 has been raised by local people of many different faiths to support a local mosque following the riots.

At a time of growing anxiety and unease, these gestures give hope and demonstrate that our communities remain strong and resilient enough to defeat those who seek to divide us.

Newsletter

Newsletter