Intimidation and harassment of female MPs is about patriarchy, not Palestine

Torrents of abuse. Police escorts. Panic alarms. The record number of female MPs is matched by record aggression — but it’s wrong to use it to score political points

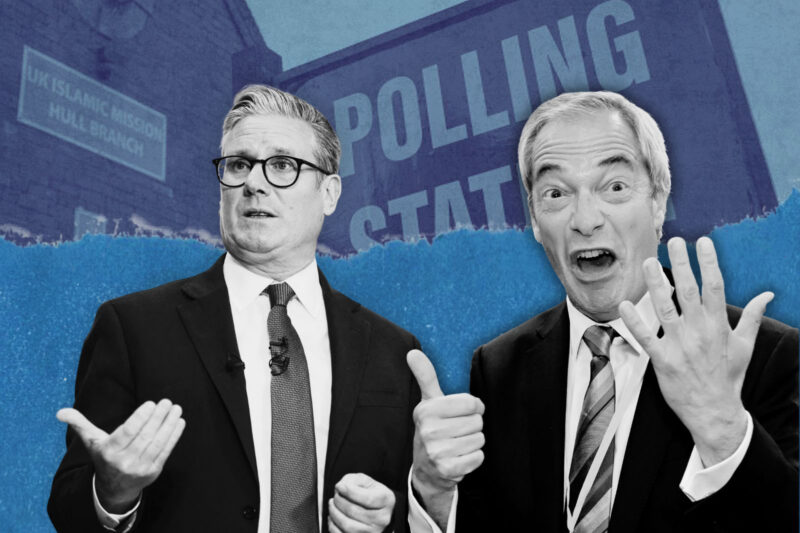

When it was announced that Shabana Mahmood had been re-elected as the MP for Birmingham Ladywood, the boos from the audience were as loud as the cheers.

The jeering came from supporters of her rival, the flashy independent candidate Akhmed Yakoob, who stood on a pro-Palestine platform, and who just 10 days earlier had been forced to apologise for joking about domestic violence during a podcast.

It was the final gasp of an ugly campaign in which Mahmood had been so fearful for her safety that she was accompanied by armed police guards on the election trail and at the count. She told the crowd: “This was a campaign that was sullied by harassment and intimidation,” calling her treatment an “assault on democracy itself”.

There were similar scenes when Mahmood’s fellow Labour MP Jess Phillips was re-elected in the neighbouring seat of Birmingham Yardley. Supporters of her rival, Workers Party of Britain candidate Jody McIntyre, chanted “shame on you” and “free Palestine” as she took the stage. Phillips told the crowd it had been the worst election campaign she had ever experienced, saying protesters had slashed the tyres of a canvasser’s car. And in Bethnal Green and Stepney, Labour MP Rushanara Ali said she had faced weeks of abuse and “spent as much time talking to the police and responding to threats and hostilities during this campaign as I did talking to voters”.

The treatment of these politicians has rightly prompted concern, and undercut the fact that we now have a record number of female MPs. But is this sort of aggression towards women in public life specific to the pro-Palestine movement?

Certain quarters of the press seem to think so. A Telegraph report the day after the election was headlined “The terrifying pro-Palestine campaign that hurt Labour — and threatens democracy”. A Daily Mail article about the election referred to Phillips’s harassers as a “pro-Palestinian mob”.

Already, crossbench peer John Woodcock — who acted as the Conservative government’s adviser on political violence — has tried, in an interview with the Guardian, to draw a link between the attempted assassination of Donald Trump by a registered Republican on 13 July, and the behaviour of “aggressive pro-Palestine activists” in the UK. He didn’t mention any other groups in regard to election-related harassment. Woodcock has form on this: in May he authored a controversial report calling for curbs on protest in Britain that targeted Palestine Action and Just Stop Oil.

While it is clear that some activists crossed the line into intimidation during the UK election campaign, such coverage fits into the existing tendency to depict advocacy for Palestine as somehow necessarily extremist. Peaceful protests have been described as “hate marches”, and in February an Evening Standard columnist described the Palestine Solidarity Campaign as “arsonists of our democracy” for protesting outside parliament during the ceasefire vote. (If peaceful protest is undemocratic, it raises the question of how exactly one might express dissent.)

What some politicians experienced went well beyond this, and they are right to call it out. Mahmood described “masked men outside meetings trying to frighten the women inside talking about politics”, while Ali’s office received a letter saying she would be “smashed and killed”.

But some quarters of the press only seem to care about abuse directed at women when it is politically expedient — especially when the abuse can be framed as coming from a racialised group, since the Palestinian cause is often seen as a Muslim issue. (It’s worth noting that the politicians concerned have been careful not to frame it this way; Phillips said that her opponents acted badly “because they were idiots, not because they were Muslim”.)

Where was the equivalent concern about Hackney North and Stoke Newington MP Diane Abbott’s democratic freedom when she was the subject of violently racist language from a Tory donor, and then repeatedly denied the opportunity to speak when the comments were debated in parliament? And where was the outcry after an Amnesty International study found Abbott had been the target of almost half of all online abuse aimed at female MPs in the lead-up to the 2017 election?

Some supporters of George Galloway’s Workers Party and the new crop of independent candidates have clearly behaved poorly. As Ali told the BBC, a handful of activists were “weaponising… legitimate anger about what’s happening” in Gaza. But these campaigners do not have a monopoly on misogyny or violence, and nor are these things new — even if the rise of social media has compounded the mainstream media’s efforts in fanning the flames of our toxic political culture. In 2016, Labour MP Jo Cox was murdered by a far-right extremist who took issue with, among other things, her strong stance on refugee rights. Five years later, Conservative MP David Amess was murdered by a supporter of Islamic State.

The gender gap in who receives this abuse, however, is significant and growing. An academic study found that, between the 2017 and 2019 general elections, the levels of harassment, abuse and intimidation faced by female MPs worsened much more quickly than they did for male MPs. By 2019, more than half of the female MPs surveyed reported that they were campaigning in fear. Black and minority ethnic women are the worst affected, with 65% experiencing some form of abuse, compared with 45% of women overall.

A 2023 report by the Fawcett Society found that nearly three quarters of female MPs were too afraid of repercussions to speak up online about issues they cared about. Caroline Spelman, a Conservative MP who was critical of a no-deal Brexit, said in 2019 that she’d had to wear a panic alarm when walking around her rural constituency after receiving rape and death threats. This year, for the first time, all election candidates had access to panic alarms and a named police contact to liaise with on security matters.

And still, of course, women are worst affected. A UK Electoral Commission survey released after this year’s May local elections included the shocking finding that more than half of female candidates avoided campaigning alone. (Just 19% of men did the same). In June, the head of Northern Ireland’s Electoral Commission warned that we’re seeing “a lower number of female representatives” because of the harassment and abuse they face. Regardless of what issue motivates political anger, the extent to which some people feel comfortable making threats and brazenly intimidating women in public life is indicative of an angry and polarised political culture, toxic online debate and unfettered misogyny.

In the Fawcett Society report, female MPs described some of the personal security measures they regularly take. Not publicising where they will be. Working with police on home security. Not running face-to-face constituency surgeries. Taking out restraining orders (long before the abuse she faced in the 2024 election, in 2021 Rushanara Ali took out a 12-year restraining order against a constituent after a sustained period of harassment). Avoiding staying alone in their homes overnight. It is not only a threat to our democracy if women cannot participate freely and without fear, but a damning indictment of our society that some of the most powerful in the country are forced to make such restrictive adjustments to their lives and work.

Some sectors of the media only seem to care about women’s safety when it can be used for political point scoring, but until we confront the fact that this is a deep-seated, wide-ranging problem, there will be no solution.

Newsletter

Newsletter