Ten years after the UK welcomed Syrian refugees, what happened to those who came?

To mark World Refugee Day, 20 June, three people resettled by the Vulnerable Persons Relocation Scheme tell Hyphen how their new lives turned out

A decade ago, the world watched as Syria’s civil war worsened and millions of refugees fled the country. This mass displacement would become known as the “refugee crisis”, when more than a million refugees and migrants arrived on European shores in one year, most fleeing conflict in Syria, Afghanistan and Iraq.

The UK government was initially slow to join the United Nation’s calls to create a refugee programme, claiming that its obligations were being fulfilled through its existing asylum and aid provision. But mounting pressure — some 3,550 people died during the journey to Europe in 2015, largely because of a lack of safe asylum routes — forced prime minister David Cameron’s coalition government to resettle some of the most vulnerable Syrian refugees.

The refugees were to be given humanitarian status to allow them to apply for asylum after five years. Cameron was keen to emphasise that only the “most deserving” of the four million displaced Syrians in Lebanon and Turkey would access the scheme and fewer than 200 Syrians arrived through the resettlement scheme in 2014.

The following year, the government faced widespread pressure from the public, NGOs and opposition parties after the body of three-year-old Syrian Alan Kurdi washed up on a Turkish beach — a tragedy that cut to the heart of the refugee experience. The Syrian Vulnerable Persons Relocation Scheme (VPRS) was then expanded to welcome 20,000 refugees.

The VPRS was closed in 2021 when it met its target, with 20,319 people finding sanctuary in the UK. The humanitarian charity Oxfam argued that this number fell far short of what wealthy nations such as the UK could provide.

“The Syrian scheme showed that resettlement programmes can be successful when government works positively and proactively with councils and charities,” says Tim Naor Hilton, chief executive of Refugee Action. “It benefited from a multi-year commitment, which allowed councils to plan, properly resource their services, and find housing.”

The VPRS may have been the exception to how the UK treats refugees. Over the years Britain has doggedly pursued hostile environment policies, most recently through the controversial legislation to send asylum seekers in the UK to Rwanda. Consecutive Tory governments have claimed that a punitive approach to immigration will deter perilous small boat crossings, but campaigners argue this can only be done by creating safe routes to entry, such as the VPRS and other resettlement schemes created for Afghans and Ukrainians.

“Resettlement schemes are a vital part of the solution to preventing deaths from Channel crossings. They give people fleeing violence and persecution an alternative to risking their lives in small boats,” adds Hilton.

A decade after the first Syrians arrived through the VPRS, Hyphen spoke with three of those who were safely resettled.

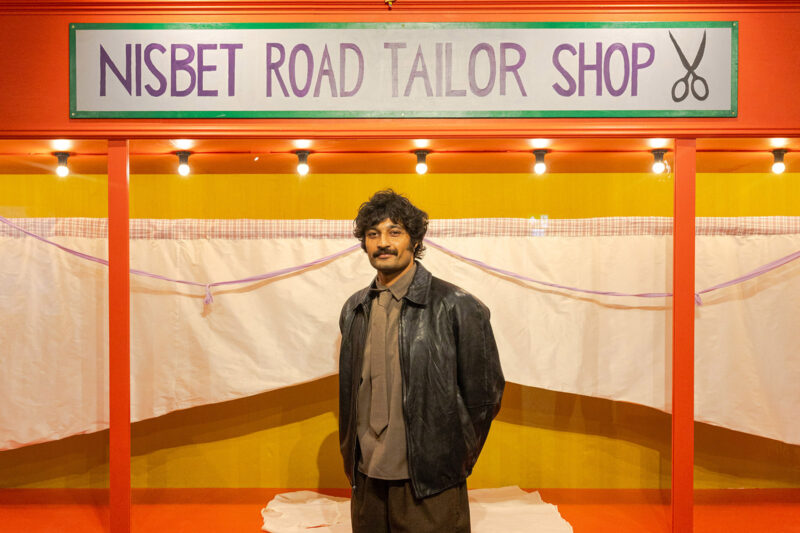

Ghani Hashas, 41, Huddersfield

“My name is Abdul Ghani, but when I came to the UK, I decided to be just Ghani,” the 41-year-old says. “Leave everything behind, all the trauma, all the wars, all the memories, and just have a fresh life with a new name.”

Hashas’ life was first torn apart by war at the age of nine. Born in Kuwait, he fled to Syria in 1991 during the Gulf war. Two decades later, he and his family sought refuge in Jordan. But, he says, “I didn’t feel like we were welcome, so we left once more.” Hashas’ eldest sister has a disability that requires medical care, so the UNHCR refugee agency referred the family to the VPRS. On the day he and three of his sisters and mother arrived in the UK in 2016, he recalls: “The big question in my head that day was to be — to live my life as best I could — or not to be? And I decided to be.”

Hashas is open about the toll this trauma has taken on his mental health: “I felt like I lost everything.” But he found Huddersfield’s community to be friendly and multicultural, helping him and his family to settle in. “One of the first things I learned is that people here have fish and chips on Friday, yorkshire pudding on Sunday,” he says, adding that he wants to try to make the latter from scratch. “I tried to learn as much about the culture as I could. English people are very friendly, as long as you don’t cross the line and ask personal questions.”

The language barrier was a challenge, but he took English classes and “would also go to the town centre, sit with older people who needed someone to talk to”. “I just tried to be kind and talk and listen to them,” he recalls. His neighbours helped to build his confidence and make him feel welcome. “They would tell me I can do this, just try.”

Hashas has been a barber by trade for the past 24 years, running his own business in Damascus. When he arrived in Huddersfield, he pursued a barbering qualification at the local college, and is now studying for a teaching qualification. His experiences inspired him to create a course tailored for other refugees arriving in the UK, and last year welcomed students from Ukraine, Pakistan, Kurdistan, Syria and Iraq. “I know the pain they’ve gone through. I also know how hard it is to study in different languages, but they’re doing amazing. It brings me happiness.”

He says he worked hard for this, but feels he wouldn’t have been able to rebuild his life without support from the resettlement scheme. “It gave me the safe passage to come to the UK. I didn’t have to cross the Channel and put myself and my family at risk. The package of support — the healthcare and education system — makes it easier for us to feel welcome and safe.”

Other refugees should be able to have this opportunity too. “Politicians have to look at us like humans, not numbers,” Hashas says, adding that he hopes to go into politics one day. “We need somebody like me to take the vulnerable voice higher and show peoples’ potential when we have the right support.”

Hashas is proud of the work he’s done to create a new life for himself and his family. “It was a sad day when I left everything behind. We have a phrase in Arabic that translates as: ‘The stone has not broken you, it has made you stronger’.”

Hanaa Alfashtaki, 37, Bristol

In 2014, as bombs dropped on her home city of Damascus, Alfashtaki, her husband and their two children were forced to leave. They arrived in neighbouring Turkey. Although the country was initially welcoming to people seeking refuge, recent years have seen increasing hostility, scapegoating and discrimination against the Syrian population. “It was not a safe situation for us there,” Alfashtaki says. They remained in Turkey while they applied to the VPRS. “The process took three and a half years. I was almost hopeless but then it happened.”

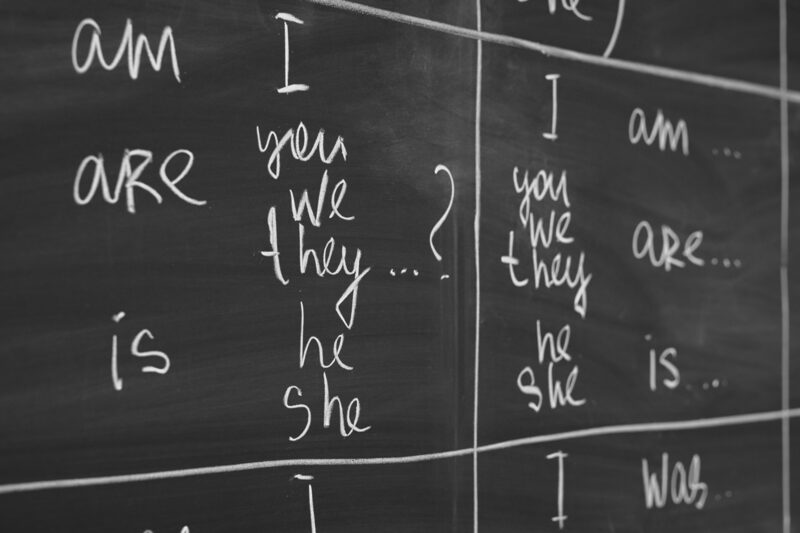

Alfashtaki and her family arrived in Bristol in 2018 after being allocated housing through the VPRS, and Alfashtaki says she’s always felt safe in the community. A local charity, Bridges for Communities, connected her with a buddy scheme upon their arrival. “They visited us weekly and supported me in gaining more confidence as I learned English,” she says.

She and her family spent the next few years attending community events run by the charity until Covid hit, which Alfashtaki describes as a difficult time. “Lockdown and staying at home was hard. It was hard for the children, too, to have to do their schooling at home,” she recalls. “But it was a difficult time for many.”

Alfashtaki earned her degree in childcare and early years education at Damascus University and worked as a primary school teacher before the war. “Teaching is my passion. From a young age, I would teach my younger siblings, helping them with homework.”

For the past five years, Alfashtaki has been teaching Arabic to adults through Bridges For Communities’ RefuLingua language programme, where classes are led by tutors of migrant and refugee backgrounds. She’s found a sense of belonging through teaching, and sees her future here. “I want my children to continue to learn and continue to pursue their studies here,” she says. “I’ve learned to drive, I want to learn other new things, like horseback riding. But my main goal is to earn a teaching qualification and go back to working as a teacher.”

Reflecting on her family’s journey, Alfashtaki says: “It is hard for me to talk about the emotional aspects in my second language. But there is a phrase in Arabic: Ibni nafsek. It means to build yourself. To keep on persisting. I tell myself to keep looking forward. The bad times will be left behind.”

Latifa Najjar, 34, Aberystwyth

Najjar hasn’t seen her home of Homs City in Syria for 11 years. After fleeing to Egypt, Najjar and her husband, their two young children, her sister and parents applied for the VPRS and arrived in the UK in 2016. “When I came here, everything changed for me,” she says. “A different language, a different life. I didn’t know where I was going and what my new life would be like.” She describes feeling in a state of shock.

However, she recalls that the community in Aberystwyth were friendly and people would often come up to her in the street to chat. “This gave me confidence to speak and made me and my family feel welcome. After around six months, I started to speak in English with friends, and my children settled in school. It started to feel like our home town.” Her children now speak Welsh, English and Arabic.

“Sometimes I walk by the sea, I see my friends on the way and we end up chatting for two hours,” Najjar adds. “It makes me really happy.”

She still cherishes so much of her Syrian culture, though she knows she will not be able to return home for a long time. Najjar and two friends set up a pop-up restaurant five years ago, serving their home dishes. The members of the Syrian Dinner Project are “like family”. “We always look after each other and help one another,” she says. Their first venture involved cooking a community buffet with meals drawing from Syrian, Turkish and Lebanese influences for 120 people. “Everyone loved it, and asked us what flavours we used for the food. I told them love, because I’m cooking from my heart for the lovely people here, because I love this place and I love the community here.”

She adds: “Wales is a beautiful country. Aberystwyth is a small town, but the mountains, sea, the river — are beautiful. I’m very lucky. If I go to visit other places, when I come back to Aberystwyth I feel like I’m back home.”

Newsletter

Newsletter