‘The UK claims to be a democracy’: How the government’s attack on protest is driving voters away

Labour has no plan to roll back the Tories’ anti-protest laws. For some, it’s proof that the ballot box won’t win change on its own

Nairobi Khan can’t remember the last time she voted. Disillusioned with electoral politics, she has found other ways to make her voice heard — such as working with Palestine Action, which has led protests around the UK against firms accused of supplying weapons to Israel.

“If your government is complicit in a genocide, it’s not going to bother with petitions,” said Khan, a domestic violence support worker in West Yorkshire. “To me, direct action is better because we’re hitting [arms companies’] pockets.”

She’s not alone. Exclusive polling for Hyphen by Savanta, published last week, found that young Muslims in particular are choosing to engage with politics outside the ballot box. Some 22% of 18- to 34-year-old Muslims have taken part in a demonstration over the past 12 months, compared with 14% of the same age group in the UK population at large.

Protests over Israel’s bombing of Gaza since October have repeatedly drawn hundreds of thousands to the streets of the UK — a mobilisation so large it has been compared to the anti-Iraq war marches in 2003.

Independent parliamentary candidate Fiona Lali believes the marches are “a reflection of the real anger that people have”. Lali, who is standing in Stratford and Bow in east London, told Hyphen: “Under the current electoral system and capitalism, there’s no real avenue for people to express themselves and have genuine representation.”

But for the past two years, politicians have seemed intent on closing off even the avenue of peaceful protest. The Police, Crime, Sentencing and Courts Act 2022 and Public Order Act 2023, originally dreamed up to target environmental protesters such as Insulate Britain and Just Stop Oil, have handed the police unprecedented levels of power. Priti Patel, the former home secretary, accused climate demonstrators of “mob rule” as she introduced one bill to parliament, following a string of protests against oil and gas production that saw activists glue themselves to roads.

As well as being able to stop and search potential protesters without reasonable suspicion, police can now restrict protests if they are too noisy or could cause “more than minor” disruption.

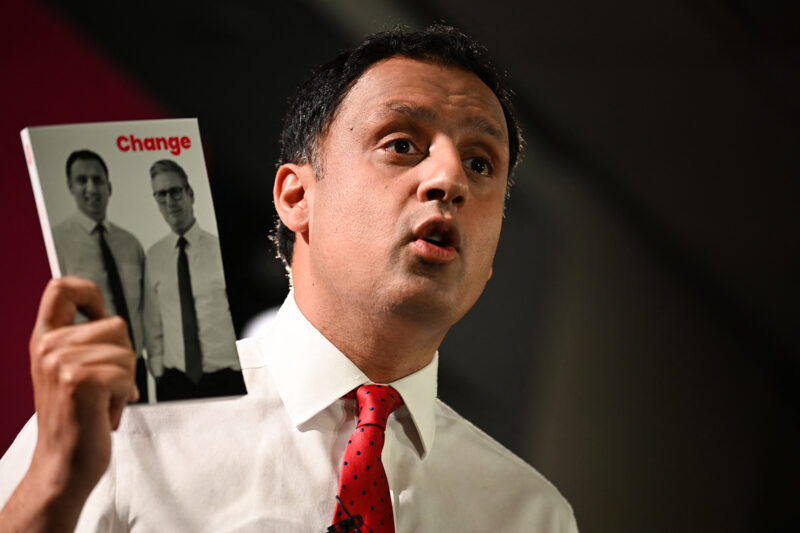

Labour has fallen in line with the Conservatives despite pressure from rights groups. David Lammy, the shadow foreign secretary and Labour candidate for Tottenham, said last year his party would not reverse the legislation. Labour even whipped peers to abstain from voting on a Green party motion to kill the Public Order Act entirely.

The eruption of pro-Palestine marches in the wake of 7 October has pushed protest back up the government’s agenda. The demonstrations have been overwhelmingly peaceful — earlier this year, it was revealed just 36 people had been charged with an offence despite a policing bill of tens of millions of pounds — but Suella Braverman, the former home secretary, insisted they were “hate marches” with “clearly criminal” elements before turning her ire on the police.

Following the row, which cost Braverman her job, crossbench peer John Woodcock made 40 recommendations on the government’s handling of protest, including the possibility of more undercover surveillance. His report, published in May, targeted groups such as Just Stop Oil and Palestine Action, who have used disruptive tactics in their climate campaigns, which Woodcock referred to as “extremist” and “apocalyptic”.

“The right to protest isn’t safe under the Tory government, and I don’t think it will be safe under Labour if they’re in power either,” said Lali, an activist and organiser who confronted Suella Braverman on GB News over the issue.

Data from polling company Techne UK suggests 20% of voting-age Britons have decided to stay at home for next month’s general election — among them, 38% of Gen Z and millennial voters.

Among those feeling alienated by party politics is east London community organiser Abdirahim Hassan, who told Hyphen he had “never been more concerned about the UK and the quality of leadership that we have”.

“The UK claims to be a democracy,” said Hassan, a trained accountant who works with marginalised groups on issues such as mental health and poverty. “Suffragettes are celebrated, and somehow young people who are protesting at the moment are not.”

Asked whether he thinks Labour will roll back the Tories’ anti-protest laws, Hassan expressed his disappointment in Keir Starmer and said the Labour leader has already “shown who he is”.

For Hassan, protesting and organising on a local level is a crucial way of expressing his dissatisfaction in both Labour and the Tories’ positions on the crisis in Gaza. As well as going on national marches, he interrupts meetings of the local Labour-run Hackney Council to draw attention to its pension investments in companies such as the Israeli-linked munitions firm Elbit UK. He also helped set up an encampment outside Hackney Town Hall last month, where protesters called for divestment.

Leanne Mohamad, a British Palestinian woman running as an independent candidate against Wes Streeting, the shadow health secretary, in Ilford North, said protest was as vital to democracy as the ballot box.

“Elections occur infrequently,” she said. “In between, politicians are often isolated in the Westminster bubble — isolated from the electorate, their opinions and problems. Issues arise, such as that of the military assault on Gaza, where the opinions of politicians and the media diverge significantly from a large proportion of the electorate. Protest is one of the ways that the people can account for their government in between elections.”

She added that, despite “the belligerence of politicians and the mainstream media”, people “have a natural sense of justice” and that her “heart has been warmed by the large number of people who have supported the protests”.

Lali agreed, adding that, while protest has always been a part of society, mounting crises such as climate breakdown and austerity politics have turned the Palestine marches into an “expression of all anti-establishment feelings in society right now”.

“That’s why they’re so big,” she said. “It’s not just Muslims or Arabs. It’s people from all backgrounds coming together because Palestine has become this lightning rod for anger, because of the way they’re policing it. And also because of the hypocrisy: the same people who are lying about the protests, or demonising the protests, are the same people who, at the same time, implement austerity.”

Since stepping down as home secretary, Braverman has continued to attack protest movements, claiming that the likes of universities are “pandering to eco-zealots, Black Lives Matter anarchists and pro-Palestinian militants”.

Meanwhile, Rishi Sunak said in a speech outside 10 Downing Street in March that “hateful” groups had “hijacked” the UK’s streets, calling for still harsher policing and claiming that “mob rule is replacing democratic rule”.

For some, the election is only a stepping stone on a longer road to change. “I’m almost less interested in 4 July and more interested in 5 July,” said Lali. “How do we prepare to organise ourselves in a real way against what will be a right-wing government no matter what?”

Newsletter

Newsletter