The enduring myth of the no-go zone

The idea of urban areas where law, order and state power have broken down has long been used against marginalised groups — but in recent years it has taken on a powerful anti-Muslim quality

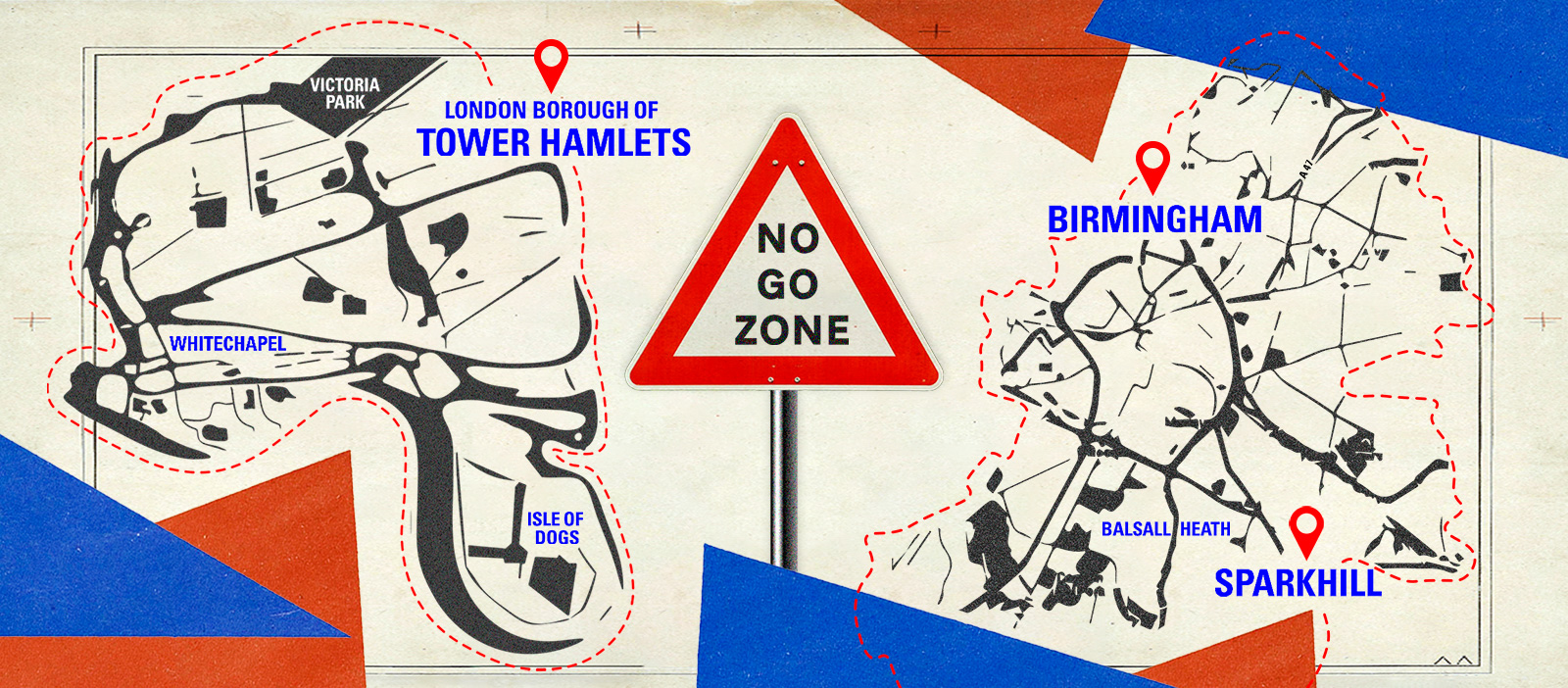

In late February, Paul Scully, Conservative MP for Sutton and Cheam in south London, went on BBC Radio London to discuss allegations of anti-Muslim sentiment in the Tory party. While denying the accusations, he made a now-familiar claim about British cities, stating that there are “parts of Tower Hamlets … where there are no-go areas, parts of Birmingham Sparkhill, where there are no-go areas, mainly because of doctrine, mainly because of people using — abusing in many ways — their religion”.

Scully swiftly rowed back on the comments, saying he regretted the language he used and that the issue was more nuanced. However, the damage was done – a media storm ensued.

Omar Tariq, 45, is a charity worker who has lived in Sparkhill all his life. When he heard the news, his immediate response was: “Here we go again.” Sparkhill is a deprived inner-city area where 92% of residents are of ethnic minority backgrounds and around two-thirds are, like Tariq, of Pakistani origin. In the BBC sitcom Citizen Khan, Adil Ray’s lead character jokingly describes the neighbourhood as “the capital of British Pakistan”, but for thousands of residents it is just home.

“It’s stupid, as everyone who has actually been to Sparkhill knows,” says Tariq. “Yes, it’s an area where a lot of Muslims live, but it’s also very diverse and there are people of all different faiths and ethnicities here, and all we’re doing is getting on with our lives.”

The reaction of prominent Brummies to Scully’s allegations was swift and dismissive. Posting on X, Ray, who is originally from the area, said: “Sparkhill is home to many communities and cultures, perhaps it’s your own prejudice that keeps you away. This is racism. Call it out. Enough.” Conservative mayor of the West Midlands Andy Street agreed, tweeting that “it really is time for those in Westminster to stop the nonsense slurs and experience the real world”. Jess Phillips, Labour MP for the neighbouring constituency of Yardley, added: “Where are these no-go areas exactly?” She then joked that “as someone who is constantly on a diet the scary dessert shops can be a challenge”.

Local newspaper the Birmingham Mail responded with a number of stories, including one tongue-in-cheek piece listing “All the no-go zones in Birmingham”, featuring the city’s university library, cathedral, botanical gardens and the world’s biggest Primark.

Tariq, meanwhile, cast his mind back to 2015. That year, during a Fox News discussion about a recent series of coordinated Islamist attacks in Paris, the US commentator and self-described terrorism expert Steven Emerson referred to the UK, stating: “There are actual cities like Birmingham that are totally Muslim, where non-Muslims just simply don’t go.” In the same interview he added that in parts of London, religious police “actually beat and actually wound” anyone not wearing traditional Muslim attire.

At the time, such ideas enjoyed relatively widespread currency in the US. Sparked by alarmist coverage of the migrant crisis and a spate of terror attacks across the continent, conservative commentators and politicians used European cities as supposedly cautionary examples of what can happen when western nations allow “too much” Muslim immigration.

While figures such as Republican governor of Louisiana Bobby Jindal went on to repeat Emerson’s claims, the people of Birmingham were quick to disagree. Over the next few days, social media users posted photographs of construction site tarpaulins as evidence that the city’s buildings were being forced to wear burqas and offered up images of the entertainment chain Mecca Bingo as a sign of creeping Islamification.

Tariq enjoyed the satirical responses, but when the idea of Muslim no-go zones resurfaced almost a decade later, he felt uneasy.

“You have a public figure describing Sparkhill as a no-go zone, which suggests non-Muslims are somehow unable to enter the area and everyone stands together because we can all agree that it’s ridiculous,” he says. “But the truth is that to some extent we do have a segregated city, we do have economic inequality, we do have racism, we do have a sense — not from everyone, but from some people — that Muslims aren’t integrated enough. It’s those issues, I think, that make a politician like Scully think it’s okay to make these comments.”

The idea of no-go zones in European cities has been a common Islamophobic trope since the early 2000s, rooted in the idea that Islam poses an existential threat to white western civilisation. But the notion of areas that are so unsafe that the state has no power and outsiders fear to visit has long been used against a variety of marginalised groups.

In the 1990s, for example, the Independent published a feature about “no-go Britain”, describing areas “which taxi drivers refuse to serve, where doctors are advised to seek police protection before making house calls, and which the police themselves will only visit in numbers”. While this iteration of the no-go-zone narrative tended to concentrate on antisocial behaviour in urban areas with high unemployment and a disproportionate density of social housing, the idea of a lawless, dangerous population has often been entwined with racial stereotypes.

“If you look at news reporting in the 1980s of riots in places like Brixton, Toxteth and Tottenham, you will see that this idea of no-go areas has a much longer history in terms of the way race is understood in Britain,” says Arun Kundnani, author of The Muslims Are Coming!: Islamophobia, Extremism, and the Domestic War on Terror.

“The whole concept trades on this idea of white victimhood, and inverts the actual reality of racial oppression. When you talk about a no-go zone, you’re talking about self-segregation, but in reality, the most segregated areas of Britain are the white suburbs. Non-white areas have always been mixed.”

Throughout the western world, inner-city crime has long been discussed in heavily racialised terms. Writing about stereotypes of Black muggers propagated by the UK press in the 1970s, the sociologist Stuart Hall asserted that the creation of such “folk devils” conveniently provides states with small and distinct groups to scapegoat and crack down on, rather than addressing deeper problems. While such ideas are usually easily debunked, public perceptions often prove far more difficult to change once they are out in the wild.

In the mid-1990s US criminologist John DiIulio coined the term “super-predator” in an article claiming that a small number of predominantly Black and Hispanic juvenile offenders were responsible for a disproportionate percentage of serious crimes in American cities. He added that in a few years “there would be 30,000 more murderers, rapists, and muggers on the streets”. By 2000, youth crime in the US had dropped by two-thirds, but the idea that ethnically diverse areas are inherently unsafe persists to this day.

According to Kundnani, the idea of the no-go zone “took on a Muslim inflection” in the UK shortly after 9/11. In the early 2000s, Labour home secretary David Blunkett announced a range of measures to address a lack of “community cohesion” attributed to the alleged failures of multiculturalism. In an interview on Radio 4’s Today programme in 2002, he talked about schools “swamped” by immigrants and doctors’ surgeries struggling to cope because so many of their patients needed “intensive language interpretation”.

As anxiety about Islamist violence rose during the so-called war on terror, fears about racial and religious segregation took on a new urgency. In 2008, then Bishop of Rochester Michael Nazir-Ali wrote in the Sunday Telegraph that Islamic extremism had become acceptable in some areas of the UK. The far right’s eagerness to seize upon such statements is clearly illustrated by the 2009 launch of the English Defence League (EDL), an Islamophobic street protest group founded in Luton, Bedfordshire, by former British National Party member Stephen Yaxley-Lennon.

From the outset, EDL members justified holding rallies and marches in areas with large Muslim communities by advancing a vision of an unrecognisable, Islamified Britain, filled with areas unsafe for white people. Britain First, a far-right political party launched in 2011, shares similar beliefs and has proved adept at using social media to spread its narratives.

While groups such as the EDL and Britain First have typically been viewed as occupying the extreme fringe of the political spectrum, their rhetoric has filtered into the mainstream and helped to normalise anti-Muslim sentiment. In February, Conservative party chairman Lee Anderson told GB News that Islamists had “got control” of London and its mayor Sadiq Khan. He was suspended before defecting to the populist Reform Party. That same week, former home secretary Suella Braverman wrote in an op-ed for the Telegraph that Islamists are in charge of Britain, and that “we need to wake up to what we are sleep-walking into: a ghettoised society where free expression and British values are diluted”. She faced no consequences.

Embedded in the phrase “no-go zone” is the notion of a place where the state has receded to such a degree that the law no longer applies. It is notable that there are rarely concrete examples of what that means, or what would happen to unwelcome individuals trying to enter such spaces. Nevertheless, the idea of Muslim-controlled areas in European cities was turbo-charged in the mid-2010s, when Isis took over vast tracts of territory in Iraq and Syria, and an estimated 5,000 Europeans travelled to join the group, including around 1,500 from Britain and 1,900 from France.

For some those developments compounded the belief that Muslim immigrants and their families formed a potential fifth column within Europe itself. In 2014, the academic and Middle East expert Fabrice Balanche labelled the northern French city of Roubaix and parts of Marseille as “mini-Islamic states”, where the government and law-enforcement agencies no longer had any authority. In the aftermath of the 2015 Paris attacks, media commentators from France and the UK referred to the Molenbeek area of Brussels, Belgium, where the perpetrators came from, as a no-go zone.

In 2017, US President Donald Trump jumped on the idea of crime-ravaged European cities, overrun by Muslim refugees and immigrants, focusing particularly on Nordic countries. “We’ve got to keep our country safe,” he said to a rally in Florida, “Sweden, who would believe this? Sweden. They took in large numbers. They’re having problems like they never thought possible.”

The next day, the British conspiracy theorist Paul Joseph Watson tweeted: “Any journalist claiming Sweden is safe; I will pay for travel costs & accommodation for you to stay in crime-ridden migrant suburbs of Malmö.” The rightwing journalist Tim Pool took up the offer, but did not find the scene Watson had described. Pool told a Swedish news agency: “If this is the worst Malmö has to offer, then don’t ever come to Chicago.”

Still, the idea that a once culturally homogenous northern European nation had been taken over by Muslim hordes took root in US conservative circles. That same year, Raheem Kassam, a founding editor of the rightwing website Breitbart London, published a book titled No Go Zones: How Sharia Law is Coming to a Neighbourhood Near You. The blurb promised reporting from California, Michigan, Malmö and London, “where infidels are unwelcome, Islamic law is king and extremism grows”.

Like many conspiracy theories, stories about Muslim no-go zones often take a seed of truth, then branch off into the realm of fantasy. One oft-cited rallying point is the existence of sharia courts and the belief that they supersede national laws. Back in 2013, for example, the EDL claimed that the Tower Hamlets borough of east London was “subject to Sharia law”.

Although sharia councils do operate in the UK, the reality is that they mostly deal with Islamic divorces and matters of community arbitration and mediation, and have no legal standing. Still, in February, the anti-fascist organisation Hope Not Hate published a survey of Conservative party members in which 52% stated a belief that parts of some European cities operate under sharia law and are no-go areas for non-Muslims.

In Tower Hamlets, Scully’s comments about the area were met with a similar sense of weary recognition to that Tariq had felt in Birmingham. “When I first started here there was an article in a US newspaper saying our no-drinking zones were because of sharia law, when they are of course because of antisocial behaviour, like every other council,” says Andreas Christophorou, director of the council’s communications department. “Sadly, it comes with the territory. Saying that, I did not expect an MP to be referring to no-go areas in our borough.”

Tower Hamlets has the highest Muslim population of any local authority area in the UK and around a third of its population is of Bangladeshi heritage. Pockets of deprivation do exist, but the borough is also home to many other ethnic groups and has recently become a hip and desirable home for young professionals. Accordingly, the council had a ready-made comeback for Scully.

Within 45 minutes of Scully’s interview, the communications department had sent out a press statement, highlighting the many attractions in the area, including the Tower of London and the Young V&A Museum, describing it as a “microcosm of an international city”. Christophorou describes the strategy as: “Tell our story, or face others telling it for us”. Many journalists who live in the borough also wrote articles in defence of their neighbourhood.

Countering the no-go zone narrative with its own story of unity and inclusion was not the only thing the council did. Since October, Tower Hamlets residents have adorned lamp-posts and other street furniture with Palestinian flags in solidarity with the people of Gaza. In March, mayor Lutfur Rahman announced that they would be removed, citing, among other reasons, that the area had already “been described as a no-go area by a senior Conservative MP”.

Referring to “inaccuracies and Islamophobic smears” in the press, Rahman said that the flags were “the focus of these media attacks”. Rahman is a controversial figure — the government has ordered an independent inspection of his leadership of Tower Hamlets council — but many local Muslims agree that their borough and, by extension, they themselves are subject to unfair scrutiny. Many, however, disagree with the removal of the flags.

“The flags didn’t make the area a no-go zone, they were about solidarity,” says Arifa Ahmed, a student based in Tower Hamlets. “Why can’t we express our political views because we’re Muslim? Why is that a threat?”

The simple fact is that the flags divided opinion in the way that many things do: some residents of Tower Hamlets were proud of the display of solidarity with Palestine; others disagreed. Before the removal of the flags, newspapers including the Daily Mail and the Evening Standard quoted Jewish residents saying they felt threatened by their presence. Others added that they were an intrusion on public spaces. Such responses underline the occasional difficulties that arise when religious or ethnic communities disagree on matters of global or local politics.

“To some extent, there’s a complicated, messy reality in the way that different communities coexist with each other in places like Tower Hamlets and Sparkhill,” says Kundnani. “There’s an ongoing process of negotiation, both within and between communities, as people figure out how to live together. That’s the story of these neighbourhoods. It’s a complex tapestry, and the concept of a no-go area is just the worst way of making sense of that.”

That messy reality is evident in recent statements surrounding demonstrations held in the UK capital calling for an immediate Israeli ceasefire in Gaza. Referring to the protests, both Braverman and government counter-extremism commissioner Robin Simcox have described the whole of central London and other parts of the city as “no-go areas for Jewish people”. However, other writers and commentators have stated contrary opinions.

In Birmingham, Tariq is still thinking about the consequences of people jumping to make impassioned defences of diversity, but not recognising the overlapping pressures that affect minority groups living in economically deprived areas. In addition to being portrayed as a turbulent and segregated place, where outsiders fear to tread, just 46% of people are employed in Sparkhill, compared to the average in England of 71%.

“I talk to young people in our area and they feel a lack of hope. Some of that is the same as young people around the country — economic problems and what have you — but some of it is social exclusion, the fact they know they’re less employable as practising Muslims. Maybe this no-go zone stuff is ridiculous, but the underlying message is that it’s threatening to the mainstream for you to practise your religion and look the way you look. That has to have an effect, somehow.”

Newsletter

Newsletter