Lina Soualem’s new documentary pieces together a puzzle of Palestinian family history

The award-winning director talks about Bye Bye Tiberias, an intimate portrait of her mother, actor Hiam Abbass

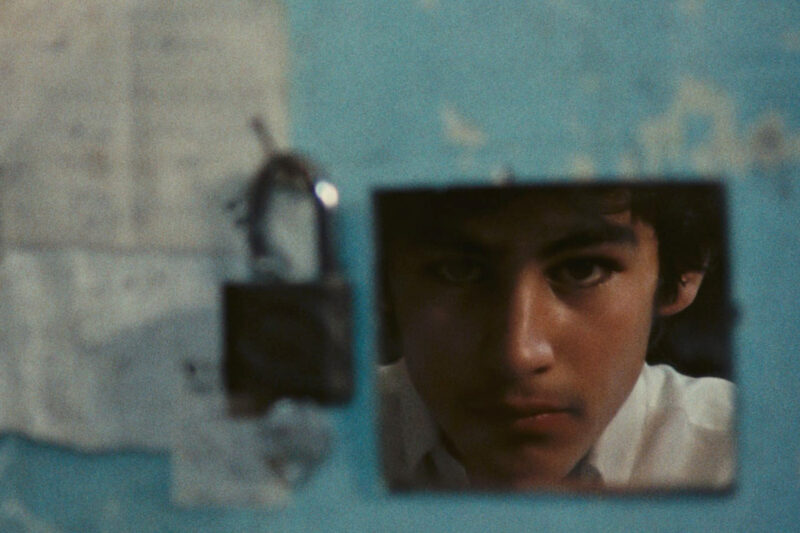

Bye Bye Tiberias, a documentary following four generations of Palestinian women in filmmaker Lina Soualem’s maternal family, opens with a 1992 home video. A camera shakily captures an azure view of the Sea of Galilee, taken from the vantage point of a moving car overlooking the water. The footage cuts to a clip of a young Soualem floating with her mother, the Palestinian actor Hiam Abbass. “As a child, my mother took me swimming in this lake,” Soualem narrates. “As if to bathe me in her story.”

For Soualem, who was born in France, making a documentary about her Palestinian family was both a necessary and daunting venture. “I always dreamed of being able to tell these stories,” Soualem tells Hyphen. “But I was affected by the fear of awakening pain, of exposing my family, of exposing ourselves with this story.” The film, which will be released in cinemas in the UK and Ireland in June by Tape Collective, recently screened at the Dublin International Film Festival. Last October, it received the Grierson Award for Best Documentary at the BFI London Film Festival.

Bye Bye Tiberias is Soualem’s second directorial effort devoted to investigating parts of her autobiography. Her debut documentary, Their Algeria (2020), explored the journey of immigration undertaken by her paternal grandparents, who left Algeria for the French town of Thiers more than 60 years ago.

Tiberias mines similar themes, considering multiple departures at once — her great-grandmother and grandmother, Um Ali and Nemat, were forced out of the city of Tiberias along with the rest of its Arab residents in the aftermath of the 1948 Nakba, while Soualem’s great-aunt, Hosnieh, was exiled to Syria. The film’s focus is Soualem’s mother Abbass, who began her acting career in East Jerusalem before settling in France in the late 1980s. Abbass’s subsequent acting credits include roles in Munich (2005), Blade Runner 2049 (2017), Gaza mon amour (2020), and the comedy series Ramy. In 2023 she received an Emmy nomination for her portrayal of Marcia Roy in HBO’s Succession.

Deir Hanna, to which Soualem’s family fled in 1948, is a place of isolation; a Palestinian village consisting of exiles from nearby Tiberias locked within the confines of the Israeli state. The neighbouring Arab countries that encircle the Lower Galilee — Syria, Jordan, Lebanon — form part of a forbidden world from which Abbass, her siblings and the residents of the village have been cleaved. “They were surrounded by borders, and surrounded by countries that they couldn’t access, that shared the same language, that shared a common history,” Soualem says.

This disconnection proves suffocating for a young Abbass, who aspires to a life beyond. Herein lies one of Soualem’s central concerns: investigating her mother’s decision to leave Deir Hanna to become an actor. “Don’t open the gate to past sorrows,” is the oft-repeated line by the women in Soualem’s family. Looking back elicits unease. “What are you after, Lina?” Abbass asks Soualem at one point in the film-making process.

Delving into parts of her mother’s personal history required Soualem to find a way to ask difficult questions. She explores Abbass’s decision to pursue a career that was unconventional in her traditional family, while examining the trauma of displacement that Abbass inherited from her own mother and grandmother. “It was hard for my mother to share some of her intimate struggles that she’d put behind,” says Soualem. “She’s used to expressing her emotions through other characters.”

What ensues is a delicate exchange between mother and daughter, now transmuted into subject and director, made easier by moments in which Soualem has Abbass wear the familiar hat of an actor. She re-enacts, rather than retells, the story of her admission to art school in Haifa, and, later, the time when she asked her father for permission to marry her first husband, an Englishman whom she met while acting in the Palestinian El-Hakawati theatre troupe in East Jerusalem.

“It was a matter of finding our balance. She had to find what made her at ease to talk about some of her choices,” Soualem adds. “This is when I decided to ask her to re-enact some moments of her younger self, so that she could also enjoy the process.”

Long-buried memories are tenderly revealed as a result. Forgoing a traditional interview style, Soualem believes, allowed her mother to tell her story on her own terms.

Elsewhere, both mother and daughter attempt to reconstruct the puzzle of their family’s story through physical mementos. While home videos shot by Soualem’s father in the early 1990s punctuate the film, family photographs help to gather dispersed memories — the pair create a collage on a wall in Abbass’s Paris apartment, consisting of photos taken across several generations: Um Ali, Nemat, Abbass, Soualem.

“Because it wasn’t easy for her to face the camera, it was also a way for me to have her communicate and transmit without being direct,” Soualem says. The process was reproduced in Deir Hanna, where Soualem asked her aunts to choose photographs of Tiberias to paste on a wall in their family home.

One of the final images in the film shows Abbass lingering on a bridge overlooking the Sea of Galilee. A group of Israeli Defense Force soldiers, barely in their twenties, walk past, their gaze momentarily resting on Abbass before a look of confusion flashes on their faces. Down by the water, Abbass reminds Soualem that this was where she had brought her as a child to swim.

In an earlier voiceover as she drives past the lake — replicating the images from the home video with which she opened the documentary — Soualem worries about the ephemeral nature of her surroundings, and her family’s place within it, speaking to the precarious nature of simply existing as a Palestinian: “I know the fear that sleeps within us. What if the remains of this place were to disappear?”

Bye Bye Tiberias goes some way to lend her story a degree of permanence, when stories such as that of her family have been erased from public narratives. “It’s amazing to see how the memories of my family, who are people from a rural background — marginalised in stories of colonisation and displacement — can now exist and are immortalised in the public space,” Soualem says. “I feel like I give back to my family their place in history.”

Newsletter

Newsletter