What can a camel teach Italians about their Islamic roots?

A Sicilian vet has opened an East African farm in the shadow of Mount Etna to educate visitors about the island’s rich and diverse history

A couple of camels – Jamila, a white female, and Ali, a brown male – munch lazily on their hay while their owner, a tall 35-year-old man, fills the water tank next to them. The idyllic rural scene could be a postcard from north Africa, except for the snow-topped volcano, Mount Etna, looming clear into view behind the animals’ stall.

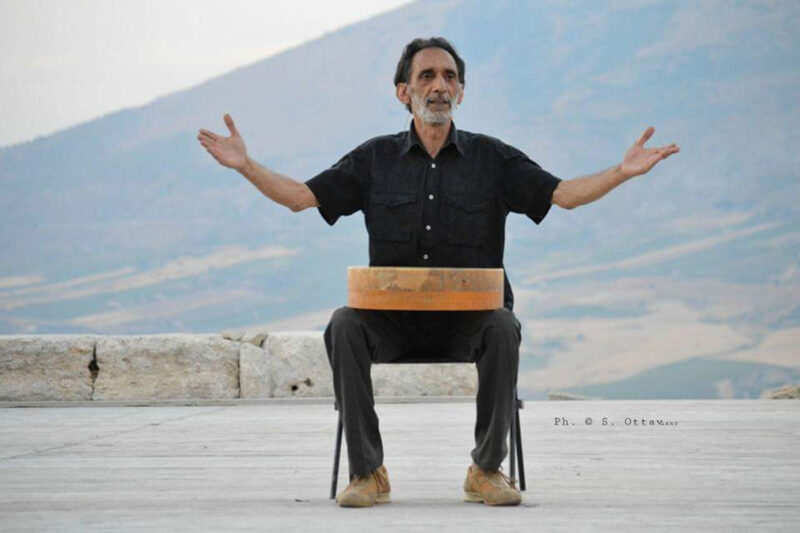

“These animals have an impressive memory, just like elephants,” said Santo Fragalà, their carer, gently patting Ali on this brisk Sicilian January morning. “But their personality is only the second thing that drew me to breeding them away from their natural habitat.”

A decade ago, Fragalà was a PhD student of veterinary medicine at Sicily’s University of Messina with no idea what to do after graduating. On the day of his final exam, one of his university professors pointed out the origins of his last name as he checked his student ID. He learned that it comes from the Arabic word farag, meaning “joy of Allah”. It is one of a dozen Sicilian last names tracing back to the region’s Islamic period – between the 9th and 12th centuries – which are still common across the southern Italian island.

“I still remember that day as a kind of epiphany. I was almost 25 and still searching for my identity, wondering both about my past and my future,” Fragalà recalled. Inspired, the newly graduated vet started to research his Muslim ancestors, their culture, politics and religion, and most particularly the local fauna and natural landscapes of their lands.

In 2013 he defended his thesis on the exotic animals of desert areas with a focus on dromedaries – Abrabian camels – and finally realised his life mission. He would fight stereotypes about Muslim countries in Italy by reintroducing Sicily to its Arabic ancestry through its animals. Specifically, camels.

“I knew it was going to be difficult because of the animals’ climate adaptation, finding the right spaces and initial investments,” Fragalà explained. “But I just really wanted to promote a return to our origins through my field of [veterinary] work and remind ourselves that we too were once a Muslim population.”

With financial help from his parents and long-term supporters of his project, a bank loan and all his savings in his venture, in 2014 Fragalà opened the gates of his dream project, Gjmàla, from the Arabic word jamal, meaning camel. A unique interactive space, it recreated a typical North African farm in the small town of Trecastagni, on the slopes of Mount Etna, Europe’s highest volcano. Gjmàla is the only farm in Italy – and only the second in Europe – producing camel milk for human consumption, including dairy and beauty products.

“My son accidentally found his purpose, but it’s through hard work and passion that he made this place happen,” said Stefano, Santo’s father, who now helps him run Gjmàla. “He’s doing something unique in his field, raising awareness on the benefits of camel milk and dismantling stereotypes about the Arab world.”

Fragalà also wanted to challenge the western gaze towards the animals. “As westerners we think we are so open-minded, but the fact that here camels are seen only as desert or circus animals shows our limited views,” he explained. “I wanted to show what non-western farms look like, to challenge mainstream misconceptions about a misunderstood area of the world.”

During the pandemic, consumption of camel milk fell as European consumers cut back on exotic products to focus on essentials – and so Gjmàla expanded its purpose. Fragalà imported new desert animals and remodelled Gjmàla as a typical Somali farm. After all, he explained, Somalia is also a part of Italian history that sadly is most widely remembered as a former colony rather than for its enrichment of Italian culture.

The newly modelled farm opened to the public in late 2021, when all Covid restrictions were lifted, as a petting zoo. Today Gjmàla hosts around 30 species of animals – from jerboas, a type of desert rodent, to Somali donkeys – and has become an educational workshop aimed at decolonising the idea of farms and farming. All the animals have Arabic names, another way of reflecting how their lives might look in their countries of origin. Ali and Jamila are still the stars of the show.

This year, new regulations came into effect in Italy under which camels can no longer be classified as livestock, threatening milk production from exotic animals. As a result, Gjmàla’s educational function has become even more crucial. Several elementary schools in the area have started collaborating with the farm and during the school year, Fragalà will open his gates to hundreds of students aged four to 13.

Fresh back from the Christmas break, a handful of elementary school students from Giardino d’Infanzia, a kindergarten and elementary school in Catania, squeal excitedly as they listen to Fragalà’s stories and explore the farm.

“Nature has numerous benefits for children’s development. They learn to develop a sense of curiosity and discovery, an emotional connection with the environment around them, but most importantly to appreciate diversity,” explained Valeria Isaia, Giardino d’Infanzia’s headmaster. “And what better place than this one to appreciate diversity beyond usual European farm animals.”

Fragalà has travelled extensively across the Arab world, bringing his experiences and knowledge back to Sicily, but this year he has a new destination on his bucket list: “My dream is to visit Somalia, the country with the highest number of camels in the world. It’s Gjmàla’s inspiration.”

Newsletter

Newsletter