Yasmine Ahmed Q&A: ‘Withdrawing from the European Convention on Human Rights would put the UK in the same bucket as Russia and Belarus’

Photograph courtesy of Yasmine Ahmed

The human rights lawyer and UK director of Human Rights Watch on the UK government’s attacks on human rights legislation and how to respond to populist movements

Yasmine Ahmed has worked in the field of human rights for two decades, having started her legal career representing asylum seekers and refugees in Australia. In 2020, she was appointed UK director at Human Rights Watch, where she advocates for the UK’s foreign and domestic policies to be consistent with domestic international human rights law.

Ahmed has previously worked as a lawyer for the UK and Australian governments and the UN at the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia. She is a well-known human rights commentator and regularly appears on the BBC, Sky, Times Radio and elsewhere.

This conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

What made you want to become a lawyer?

I saw it as an instrument to bring about change. I have always been deeply committed to human rights and trying to make some kind of difference to people who are suffering. I had actually initially thought that I wanted to be a journalist for that reason, and I did a journalism and law degree. I felt the law provided a way of fighting for protecting rights that really spoke to me.

Are there any specific cases in your career that have stayed with you?

I was brought up in Australia, where I worked with asylum seekers who were subjected to being put into mandatory detention. These were essentially prisons in the desert in Australia where 12-year-old-boys were trying to kill themselves because of the horror that they experienced in these mandatory detention centres. The fact that years of people’s lives were robbed from them, that will never leave me.

Describe a typical day in your role at Human Rights Watch?

At any one time, I’m working on multiple countries and situations around the world in which Human Rights Watch is documenting harms. We work in more than 100 countries in the world and in addition to that, there are a number of thematic issues that we work on such as corporate due diligence, economic justice, women’s rights and LGBT rights.

As the key Human Rights Watch representative in the United Kingdom, I also work on both UK foreign policy and domestic policy. The domestic policy work has been very heavy, given the assault that we’ve seen on rights.

What are you concerned about in the UK regarding human rights?

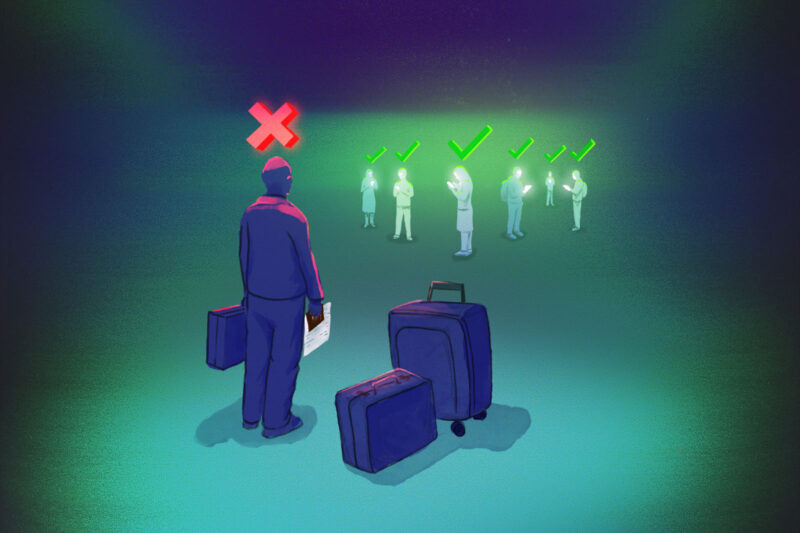

What I think we’re seeing with the UK government now is an attempt to try to find ways to push aside human rights to achieve a political agenda, and it’s very dangerous. And it’s not only in the form of trying to water down human rights legislation, but also, very perniciously, in the form of making it more difficult to challenge the government.

The UK government has also made noises about pulling out of the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR). Is that possible?

It’s certainly possible for the government to withdraw from the European Convention on Human Rights. The political implications and ramifications of that would be extreme: we would be in the same bucket as Russia and Belarus, of having withdrawn from or defied the convention. It would not mean that human rights obligations would fall away, however, because the UK is still party to international law and a number of human rights conventions. And also we still have our common law in the UK and the Human Rights Act.

What effect would leaving the ECHR have on day-to-day life for people in the UK?

A lot of people see rights as something that’s for other people, not for them. But it’s only when maybe a family member of yours may have died in circumstances where you’re not aware exactly of how it happened and you want an inquest into that, that you realise actually your right to an inquest follows from and flows from your rights under the European Convention on Human Rights.

If you’re a woman in the UK and you’re seeking to leave a situation of domestic violence, your right to seek protection is another right under the European Convention on Human Rights. There are a whole lot of rights which are very relevant for people’s everyday lives.

But in the rest of Europe, the far right is in ascendance. How do human rights advocates respond to that?

We can’t dismiss why people are attracted to a populist narrative. It has nothing to do with them not understanding or being stupid or not having enough information before them. There’s a sense that the social contract has been broken and I think that’s played out most prominently in the form of economic inequality.

How do countries like the UK respond to challenges from conflicts in Ukraine, Sudan and Israel/Palestine?

I think the biggest challenge we’re going to have is the faith that people have in the international institutions and the International Criminal Court, and the sort of international rules-based order delivering effectively and impartially, because what we’ve seen are incredibly stark double standards. And that plays out very, very viscerally for a lot of people. There are a lot of people who are saying, “To what extent does the colour of my skin or my nationality play a part in how my rights are protected?”.

We are coming up to an election which Labour is widely expected to win. What do you expect and hope for from a future Starmer government?

Labour have said that they are not going to withdraw from the European Convention on Human Rights. That’s a pretty low baseline, but it’s where we are. But, in addition to that, they have said that they will withdraw the Rwanda deal and try to seek to amend the legislation that essentially criminalises and makes it unlawful for people to claim asylum in the United Kingdom.

But we need more than that. We need them to go further and to make commitments that rights will be at the centre of how they envisage what they are going to do going forward, whether that’s the right to economic equality or the right to universal social protection.

Newsletter

Newsletter