A piece of paradise blooms in Cambridge

On the site of Europe’s first eco-mosque, a group of female volunteers come together to plant flowers and grasses ahead of the coming spring

–

It is a cold, rainy morning in early November when I arrive at the Cambridge Central Mosque. A small group of volunteers is huddled around the mosque’s head gardener, Helen Seal, who is assigning duties for the day. As the deep winter approaches, weathered plants need pruning and soil must be prepared for the coming spring.

The volunteer group is made up of four women of Pakistani, Bangladeshi and Sri Lankan heritage who have been coming to the garden every Wednesday since its opening in 2019. Some are keen home gardeners and jumped at the chance of working in the mosque.

“It’s a blessing to help enhance and facilitate the beauty of God’s creation,” said one of the women, Nabila Winter. “As a community, we are underrated and overlooked as people who are very connected to the earth. So many of our parents and grandparents were growing spinach and coriander in the garden growing up. It’s who we are, we have always worked with the land.”

The garden sits at the front of what has been described as Europe’s first eco-mosque, designed to provide a calm oasis amid the hustle and bustle of the city. To minimise the mosque’s carbon footprint, architects chose timber — one of the most sustainable materials available — as the primary medium in its construction. The prayer hall, which accommodates 1,000 worshippers, is fitted with roof windows to minimise the use of artificial light during daylight hours, and a large solar panel arrangement powers all hot water, air cooling and 13% of the heating throughout the building.

A green space to enhance the mosque’s sustainability was seen as essential. The garden project was led by landscapers at Urquhart & Hunt, water feature specialist Andrew Ewing and Emma Clark. Clark, who specialises in Islamic garden design, has also consulted on an Islamic courtyard garden in Holland Park, London, the garden at Shah Jahan mosque in Woking, Surrey, and landscaping at the British Muslim Heritage Centre in Manchester.

Respect for the surroundings, biodiversity and insect-friendly planting was crucial to the design and selection of plants. “The Islamic garden is rooted in an understanding of what is good for the environment. As Muslims we believe that everything in nature is a sign of God, and the Qur’an teaches us that we are stewards of the earth,” Clark said.

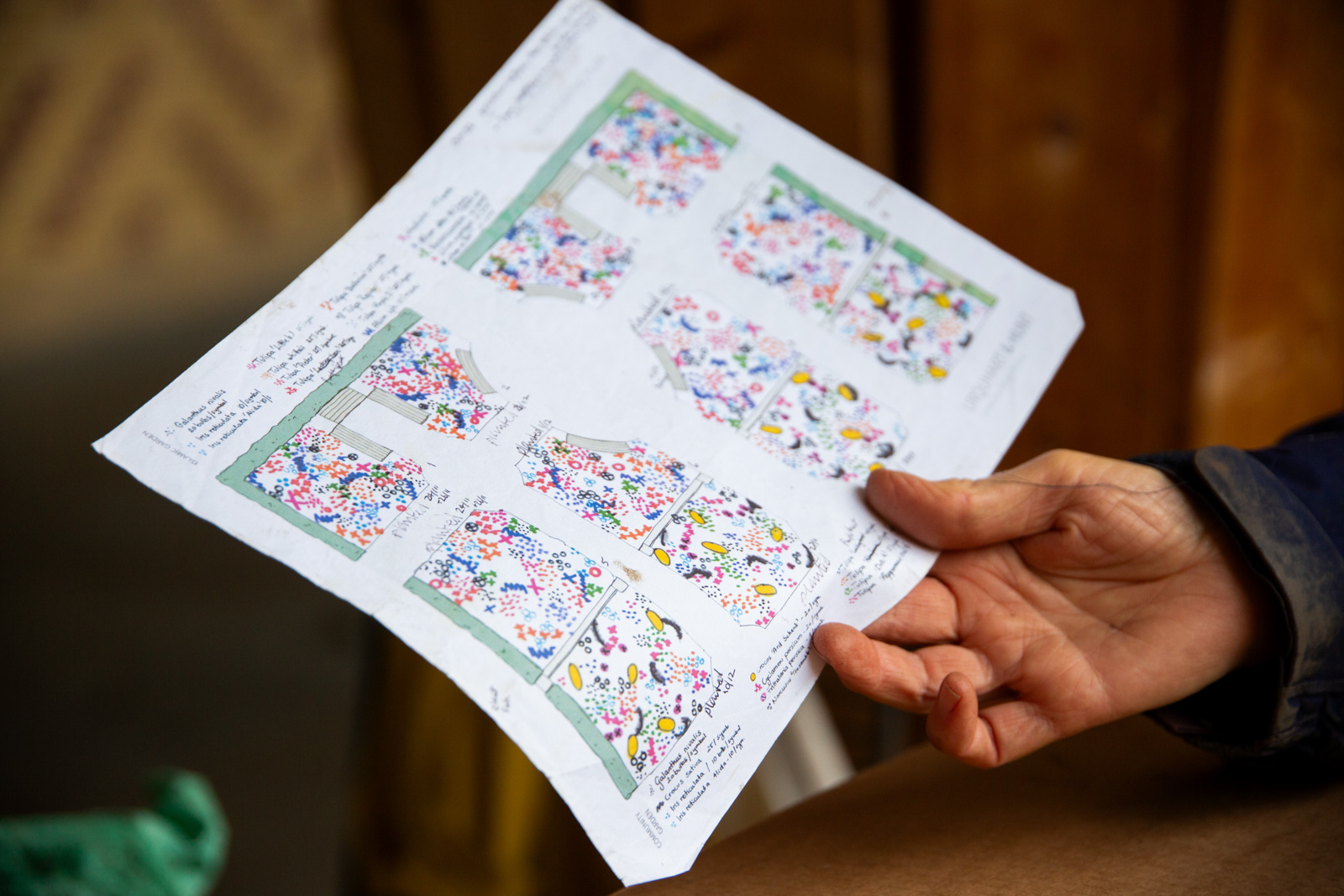

Measuring over 300 square metres, the garden was inspired by descriptions of the heavens in the Qur’an. At the centre is a large stone fountain, with four pathways — symbolic of the four rivers in paradise — leading to 12 planted beds that have been arranged in quads to reflect the four gardens of Jannah. Some 750 flowers, including tulips, snowdrops, crocuses and alliums, plus herbaceous plants, shrubs and grasses were planted in each bed to create a rich carpet of colour.

On the morning I visit, Seal, who works at the garden part-time, is handing the volunteers small plastic bags of tulip bulbs. “We’re putting another 50 to 100 in each bed to refresh them,” she said. They are also planting irises, which Seal hopes will extend the garden’s flowering season.

“We currently have crocuses that flower in February, a lot of tulips that flower in April and May, and now we are planting irises, which will flower in May and June.”

Since the garden’s opening, Seal has been working to ensure it remains completely organic, meaning that it is free from pesticides and man-made fertilisers. The gardeners have recently introduced ladybirds and nematodes to fight off pests, and worms to improve soil health. The team also makes their own compost and mulch, which reduces weeds and locks in moisture.

“The theory is that if you look after the soil, the plants will grow healthy and well, and therefore you don’t need chemical inputs,” Seal said.

Traditionally, Islamic gardens have encouraged visitors to forge deeper connections with their faith, by providing a space to reflect on God’s creation that also serves as a reminder of paradise. The essential elements of their design include a focus on shade and water, and appealing to the senses through scent, colour and touch. However, the plants in the Cambridge mosque’s garden must also be able to withstand the dry climate of the city, which averages less than 23 inches of rain a year. The chosen plants include heavily-scented Russian sage, rosemary, Damask rose, jasmine and a flower called Daphne Eternal Fragrance.

Another consideration is that the mosque sits above an underground car park, which means the garden soil is limited to a maximum depth of one metre. This has made it difficult for some plants, such as the four mature crab apple trees near the mosque doors, to grow to their full potential.

“Usually, you start with smaller trees, and let them grow into the space. The designers chose big trees because they wanted to make an impact, but they struggle because they don’t have a lot of soil,” Seal said.

Although most plants have thrived, the designers were aware that some might not. “Each bed has the same sort of plant but in different places, so that gives a rhythm of familiarity, but it means that if one plant dies it doesn’t look all wrong,” Seal said.

The dry soil is also partly because the gardeners keep watering to a minimum for sustainability reasons. Exceptions are made only when trees are in danger of dying, as is the case for four silver birches at the front gates. Seal said designers would ideally have planted Italian cypresses there, but before the mosque was built the site had been home to a small community garden, which had a birch.

“Birches are not suited to this particular situation because they like moisture, so we have had a real job to keep them alive,” Seal said. To counter this, the gardening team has been watering the trees using irrigation bags filled with rainwater captured from the roof and filtered ablution water.

While the environment has been a key consideration in the design of the mosque and its garden, so has the local community. Four of the beds are situated outside the gates, along the pavement beside busy Mill Road. Clark said the intention is for the beds to attract the curiosity of passers-by and for the garden to serve as a bridge between Muslim worshippers and non-Muslims.

Volunteers told me about drawing classes that had been held in the garden, and that staff from the nearby Brookfields Hospital often spend their lunch breaks there in the summer.

“It’s so much more than just the mosque garden, or the Islamic garden,” said Winter. “For me, the most outstanding feature is how much joy it gives people, and the community it is creating.”

Topics

Get the Hyphen weekly

Subscribe to Hyphen’s weekly round-up for insightful reportage, commentary and the latest arts and lifestyle coverage, from across the UK and Europe