The Iraqi storyteller reviving Sicily’s Arabic culture

Yousif Latif Jaralla is using his passion for oral narration as a tool for integration and understanding

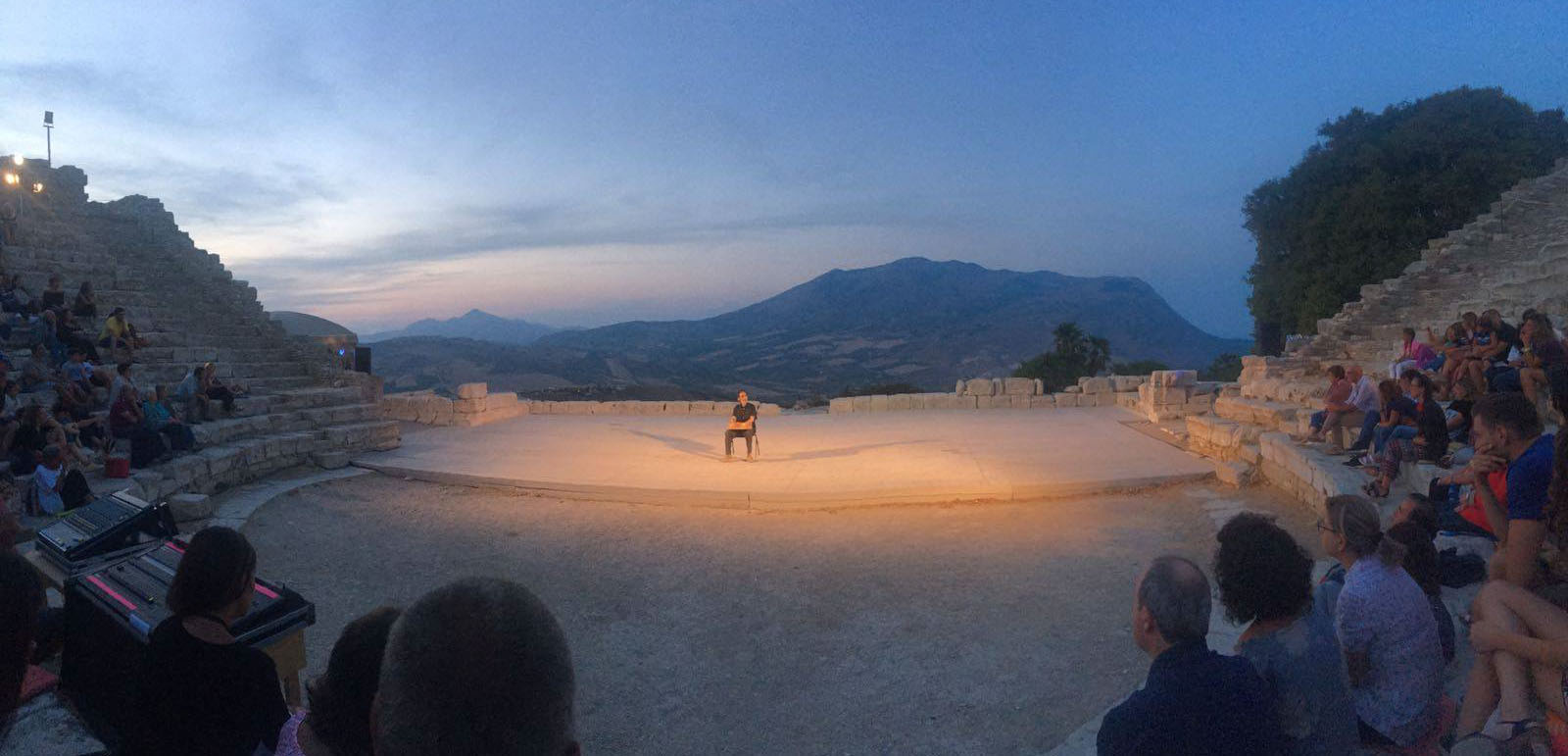

Accompanied by the rhythm of a drum, the voice of Yousif Latif Jaralla — a slender 64-year-old Iraqi storyteller with an intense gaze — resonates across the main hall of Mare Memoria Viva, a modern museum in the heart of Palermo, Sicily.

On this crisp November evening, an audience of around 100 people has come to see his 50-minute show, Amadou in the Belly of the Whale, the story of an African migrant risking his life to reach Europe via sea. It is one of more than a dozen shows that Jaralla has staged in the city that has been his home for the past 30 years.

“I try to convey my fascination for the similarities between [my] two cultures and, at the same time, promote integration by tackling contemporary issues such as conflict and migration,” Jaralla said after the performance.

Back in Iraq, Jaralla studied medicine at the University of Baghdad, but says he preferred to spend his days listening to hakawatis — traditional oral storytellers of the Middle East — in the city’s smoky bars downtown. There, he became fascinated with oral narration.

In 1980, when he was 21, a war broke out between Iran and Iraq, forcing him to flee the country. After crossing Turkey, he reached Italy by train. “It’s then that my life took a completely different turn, and not just because of the exile,” Jaralla said. He couldn’t transfer to the medical faculty because at that point he didn’t speak Italian. “My only opportunity was to enrol in an arts school, where words weren’t necessary.”

After obtaining a degree from the Academy of Fine Arts of Rome, Jaralla travelled across Italy but never seemed able to find his place or calling until, in 1990, he visited the southern city of Palermo. With its urban chaos and Arab architectural features, it immediately reminded him of home. “Palermo is one of those cities with a heart, where an outsider feels welcomed, not just put up with,” he said with an affectionate smile.

For more than 200 years, between the 9th and 11th centuries, Sicily was the stronghold of an Islamic Emirate and that influence is still very much recognisable in the architecture and food as well as the language — the local dialect uses many Arabic words. Inspired by this common past, Jaralla started to investigate potential similarities between the Sicilian and Arab storytelling tradition he had loved so much in his youth.

Anna Sica, a Sicilian theatre historian, explains that the art of Sicilian oral storytelling, locally known as cunto, became popular in the first decades of the 19th century but the stories brought to the stage then dated back to the Middle Ages and were specifically about the Christian crusades to conquer Jerusalem, or the French battle against the Moors to take Sicily.

“Many characters would be Muslims and have Arabic names, so there is definitely a significant Arab presence in our traditional storytelling heritage,” Sica explained. The voice tones and rhythms of the performance, as well as the storyteller’s technique of speaking in metric verses, are also drawn from the Islamic tradition. “The main difference is that in Sicily storytellers would accompany their narration with wooden puppets, or pupi — a tradition called opera dei pupi.”

Despite the language barrier as a non-native speaker, Jaralla felt motivated to bring his own touch to the tradition — a compromise between the hakawati and opera dei pupi — to bridge the gap between his two homes.

More than a decade ago, he started collaborating with Mimmo Cuticchio, Sicily’s cuntista maestro, a descendant of one the most important families of puppet storytellers of the island.

“For us they were not ‘Arabs’ or ‘Muslims’, but simply characters of our stories, of our tradition,” Cuticchio explained. “What our storytelling traditions have in common is the emphasis we put on the stage presence and narrative tones, rather than the story itself.”

Five years ago, Cuticchio and Jaralla worked together on Aladeen of Many Colors, a cunto show inspired by the One Thousand and One Nights. In the show, the two storytellers alternate a narration in Arabic, Italian and Sicilian dialect, and share the stage with caricature puppets of themselves. This performance had widespread success, touring outside Sicily. Jaralla’s solo performances are just as popular.

Valentina Chinnici, a middle school teacher in Jaralla’s audience on 3 November, has seen him perform many times. “For us he’s fully Sicilian. The fact that he’s Arab was not a cultural shock for us. We have the same tradition,” she said.

She believes that what worked to make the Iraqi storyteller stand out and be accepted in such a niche Sicilian industry was his innovative vision to address contemporary topics. Jaralla is, so far, the first and only cuntista to apply modern issues to the centuries-old tradition.

His mission has brought him to schools and jails as he hopes the beauty of storytelling will help students and prisoners to find their voice as he found his. Sicily is one of the principal points of arrival for migrants and refugees to Europe, and between 2016 and 2017 Jaralla held storytelling workshops to help new arrivals to tell their own stories.

“I owe it to this city and its newcomers looking for a new beginning,” Jaralla said. “I would never have remained here for more than 30 years and kept doing what turned out to be my life mission if I didn’t find a place to feel welcomed and appreciated as I did here.”

This article was amended on 21 November 2023. An earlier version said that for about 300 years, between the 10th and 11th centuries, Sicily was the stronghold of an Islamic Emirate. This has been amended to say more than 200 years, between the 9th and 11th centuries.

Newsletter

Newsletter