The Moroccan YouTuber who is reviving Spain’s shepherding tradition

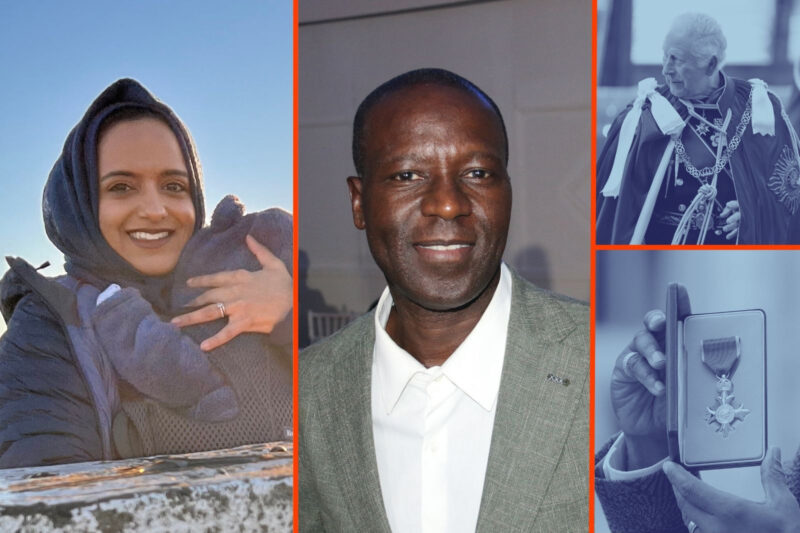

Abdul Moundir, a mechanic from northern Morocco, has become an online hit with viral videos about his new life in Spain as a shepherd. He believes hard work and passion can save the country’s struggling lamb industry

–

On an unusually hot October afternoon in the hills outside the small Spanish city of Tudela, Abdul Moundir’s sheep graze lazily on the few patches of grass left unscorched by the harsh sun. It’s time to take the flock to the watering hole, he tells his assistants Miloud Jebbour and Boukhlidj Besseghir. With his sheep dog, Patchi, running swiftly behind, pushing the animals along, Moundir advises the young Moroccans to improve their Spanish if they want to succeed in the shepherding business. “You need to spend time with locals to learn the language. It’s the only way.”

At home in Sraghna, northern Morocco, Moundir was a mechanic but in 2014 he decided to join four of his brothers living in Spain, “in search of a better life”. He took the first job that would give him the residence and work permit he needed to stay in the country. That happened to be shepherding. He found a job working for shepherds in Navarre, a part of northern Spain famed for its agriculture and the Running of the Bulls festival, and spent seven years with them learning the ropes of a slowly dying profession.

While still working for other shepherds, he launched a YouTube channel in Arabic sharing tips and stories from his life with the sheep. He didn’t set out to make money from the channel, just share his knowledge, but after a month he had already reached YouTube’s subscriber requirements for monetisation. Today, his channel has 248,000 subscribers and his Facebook page has more than half a million followers. The most popular video, in which he explains what to do if a sheep falls over on its back, has 7.7 million views and counting.

Most of his viewers come from Morocco and Algeria, and he frequently receives messages from others thinking about making the move to shepherding and to Spain. Jebbour, who now works for Moundir, was picking grapes on a vineyard in the neighbouring region of Castile and León when he saw him on YouTube and reached out to him for advice. Moundir took him under his wing, and he recently bought his first 500 sheep.

“I received a lot of solidarity and support from the channel. It’s really been a lifeline,” Moundir said. It was his followers who encouraged him to get his own flock two years ago, and now he wants to give back by helping others. With the money he made from YouTube and an investment from one of his subscribers, he was able to set up his own business in the small village of Ribaforada, where he now lives with his wife and two young daughters, both born in Spain.

“All of this cost me €185,000,” he said, pointing at the sheep and the brown rolling fields around him parched by a dry and hot summer. “Now I have 1,900 sheep and I’m going to get more. If you’re working toward something, work towards something big.”

Spain’s tradition of family-run sheep breeding businesses is struggling to survive in España Vacía [Empty Spain], as young people leave their rural communities in ever greater numbers for the city. Shepherding is no longer an attractive way of life for young Spaniards, Moundir said. “Young people want to work from Monday to Friday and have free time on the weekend. The majority don’t want to know anything about the countryside, or about sheep.”

Spain is still the biggest producer of lamb in the European Union, with Navarre in particular well known for its tender suckling lamb. However, lamb consumption within Spain has fallen by half since 2003. The EU’s sheep population has also declined by 1.8% in 2022, with Spain and France accounting for 57% and 36% of this drop respectively. This has prompted many Spanish shepherds to question the future of the industry. Moundir, however, is convinced there is one, as long as you’re willing to put in the work.

Pilar Larumbe Martín, who teaches agricultural entrepreneurship at INTIA, a public institute promoting agriculture in the region, explained that those born into the industry start with a huge advantage, benefiting from knowledge, land, and sheep passed down through generations. Moundir, on the other hand, had to start from scratch. He took a 200-hour course offered by INTIA to help young people start a business in agriculture and was awarded a €37,000 government grant.

Today, shepherds are not only required to manage the land, create a good product and sell it, they also need skills in marketing and sustainability, explained Ane Gartiziandia Gabiolond, who teaches shepherding at Gomiztegi, one of the country’s few shepherding schools. “It requires a big investment, and the situation is difficult. There are people who manage to make a living from it, but you have to like it a lot,” she said.

For Moundir, all this goes without saying. “You get addicted to it and you have to see the sheep every day to make sure they’re OK, otherwise you go a little crazy,” he said.

Without local contacts, he admits, it can be difficult to reach the right officials in city hall to negotiate the rent of land and sheds — or corrals — where the animals sleep. Moundir’s ten corrals alone cost him €32,000 a year. Animals are easier to come by. He bought his sheep from disillusioned local shepherds who decided to retire or whose children didn’t want to continue the family business. Several shepherds around Ribaforada have already sold all their cattle and in ten years’ time, Moundir believes, it will mostly be immigrants like him sustaining Spain’s shepherding tradition.

According to the latest government data, 773,000 Moroccans have Spanish residence permits, making them the biggest migrant group in the country. However, social exclusion is a widespread problem and a recent study showed that 27% of Spaniards consider Moroccan immigrants a threat to the Spanish economy and 23% believe that they’re a threat to the country’s culture.

In a conservative region such as Navarre, where the far-right Vox party tripled their votes and entered local parliament for the first time following May’s municipal elections, people can be suspicious of foreigners. In Ribaforada, however, locals fondly refer to Moundir as “the guy with the sheep”.

“In the beginning, some people are suspicious because of your nationality and don’t trust you to pay the rent for the corrals and the land, but after they see that you do, it’s fine,” Moundir explained. “If I’m in Ribaforada and there are corrals being put up for auction, I’m the first one who gets to choose because I’m from the village. Even if there are Spaniards coming from the neighbouring villages, I get to pick first. Those are the rules.”

Moundir’s hard work is paying off. His business is going well. The price of meat has gone up ahead of Christmas and he’s selling his lambs for as much as €90 each. He plans to keep sharing videos and his passion for shepherding in the hope that he will inspire enough people to save the dying tradition he has come to love. He wants to grow old with his sheep. “Whoever gets into this to make money is going to get ruined,” he said. “You have to get into the sheep emotionally, because you love them. And then they will give back to you.”

Newsletter

Newsletter