How charity shops are taking on big fashion

For Gen Z Muslims thrifting isn’t just following trends — it’s an act of faith too

Vintage is in. From cargo trousers and dungarees to trends such as low-rise jeans, pleated miniskirts and nylon handbags, Gen Z crowds are increasingly reappropriating fashion fads from eras long behind us.

At the heart of this continual sartorial recycling are charity shops and secondhand stores. Long a treasure trove of bygone aesthetics, the market for secondhand clothing as a whole has grown by 30% since 2022, reaching £2.5 billion, according to industry market research analysts IBISWorld.

The humble high-street charity shop exerts such influence on fashion that, rather than being a place where style goes to die, it is often looked to as a source of inspiration by luxury designers. Samaira Latif, a former M&S buyer who now buys for the retail giant Landmark Group in the Middle East, says she often scours thrift shops for ideas, from pattern designs to vintage materials. “I can tell you, everyone from River Island, Asos, M&S, H&M, Zara — we all do the same,” she says.

Nabeela Zaman, managing director of British Bangla Welfare Trust, a charity shop in Stratford, east London, believes that sourcing fashion from secondhand shops is both economically smart and a more authentic way to seek out vintage trends than buying new clothes that imitate older styles.

“People don’t go out to shops all the time, and we live in a world where everything is at your fingertips, and super-cheap,” she says.

In contrast to the ease of fast fashion, Zaman believes that a major appeal of the charity shop is the requirement of having to visit in person, putting in the time and effort to discover pieces, and to be creative with what’s available. When shoppers are seeking garments that have been touted as stylish must-haves for the season and are rooted in old trends, it makes all the more sense to source them second hand. “People who want the authentic thing will come to us,” says Zaman.

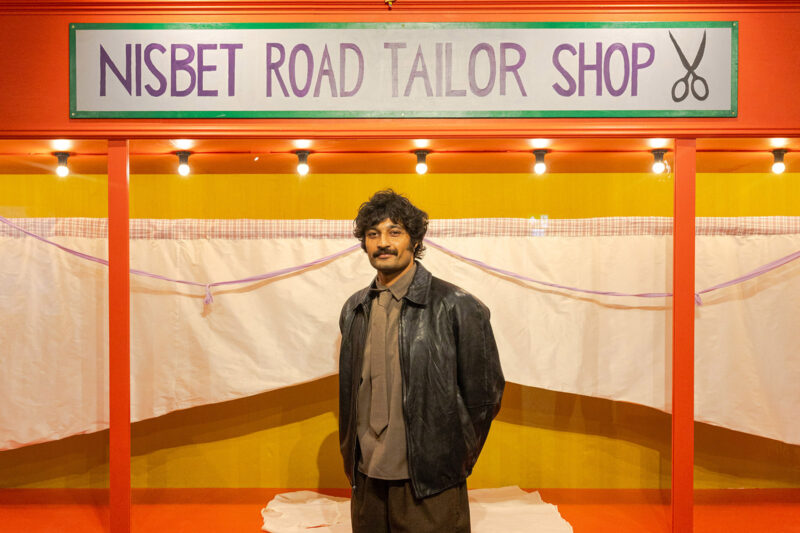

Zaman’s father opened the shop in 2020, selling donated goods to help fund projects such as feeding and clothing homeless people in the local community in east London, as well as back home in Bangladesh. But while the founders may be South Asian Muslims, and much of the store’s stock is donated by Muslims, Zaman notes that she sees relatively few Muslim customers buying clothes from there.

“For some people, the idea of wearing other people’s old clothes is strange,” she says, adding that within the local Muslim community there is a sense of pride that stops people wearing secondhand clothing.

The attitude appears to be a cultural one. Latif, who relocated from the UK to the United Arab Emirates and owns a wardrobe that is 50% vintage, notes that there is a serious lack of thrifting outlets in the Middle East. “In this region, new items hold more value and regard,” she explains. She recalls going on a work trip to New York, where her Arab colleagues couldn’t grasp the fact that she was shopping for previously worn clothes.

Among younger Muslims, however, attitudes to thrifting are beginning to change. As young people become more conscious about climate change and ecological sustainability, some see buying second hand as a religious and economic duty. Zaman says she personally strives to follow the lessons and lifestyles of the prophet Muhammad’s family, who are known to have lived frugally, with minimal waste.

“As a Shia Muslim, I would say that I try to live by the ethos of Imam Ali as well as the rest of the Prophet’s family,” Zaman says. “One thing he kind of lived by was the morals of justice and fairness, and I guess trying to be on the side of truth, even when you’re a minority.”

Tara Alia Khalid, an avid buyer of secondhand clothing based in Banbury, Oxfordshire, shares Zaman’s views, citing a verse reminding Muslims that Allah “likes not those who commit excess”.

Her passion for secondhand clothing was initially born of necessity. “I grew up in the north of England, below the poverty line, so secondhand shops were the only way I could afford to get nice-quality clothes,” she explains.

More than a decade ago, Khalid became more aware of the dark side of fast fashion, from the environmental damage it causes to the poor conditions endured by factory workers. Since then, she has bought only second hand.

“As I got older and learnt what mass production was, I just couldn’t comprehend why new clothes were being made. It sounds like we already have enough to clothe everyone, so I should stop buying from new and buy from what already exists. To do otherwise is wasteful,” she says.

In that time, she has had some memorable finds, including a real leather trench coat found at a charity shop for just £25 in 2012 to a bow-adorned pastel pink Lolita-style jacket she bought at a thrift shop in Japan in 2019 for just £15.

Vintage and secondhand shopping has also surged in popularity, in part owing to social media. Thrifting-related content, from vintage hauls to “outfit of the day” videos on TikTok, regularly rack up millions of views. With more than 3.5 million YouTube subscribers and 1.5 million Instagram followers, Ashley Rous, otherwise known on Youtube and Instagram as ‘bestdressed’, made a name for herself through filming thrifting hauls, and now promotes high-end brands including Gucci and Tommy Hilfiger.

Among other vintage fashion influencers, there is an array of aesthetics. From cinchonasthrift’s colourful, contemporary outfits sourced from vintage and secondhand shops to mrstdupuy’s classic, old-glamour ensembles from her vintage finds.

Many of these influencers promote apps such as Vinted and Depop — marketplaces where users can buy and sell used clothing online, creating an entire ecosystem that physical charity and secondhand shops now compete with.

Online secondhand clothing apps are rife with their own weaknesses, often conflicting with the notion of sustainability altogether. “I don’t like how insidious ‘outlet’ businesses masquerade as secondhand. Their prices are often cheaper than fast fashion and it just looks exploitative,” Khalid points out. Even when she filters by “auction only” or “second-hand only”, these outlet business results misleadingly appear in the results, labelling themselves as secondhand when they aren’t.

And while it may have humble intentions, the realm of secondhand shopping can become snobbish, for some. Zamaan believes that some online thrifters favour carefully curated, high-end vintage boutiques over small, local charity shops and are willing to pay more for items from outlets they view as more prestigious.

“I would love to do a special experiment and sell the same shirt in a charity shop, a thrift shop and a vintage shop — I can guarantee it would sell at different prices,” Zaman says. She also notes that the success of secondhand stores is also dependent on location. If a charity shop stands in a low-income area, it won’t attract well-to-do shoppers who would opt to go to more expensive boutiques, even though the quality of the clothing may be comparable.

Despite the increased competition from specialist vintage outlets and fast-paced online marketplaces, Zaman believes that charity shops are unique, offering an experience that encourages customers to think about where the clothes they wear actually come from.

“These are items that somebody else has already owned and there are probably great stories behind them,” she says. Zaman embraces that idea not only by wearing secondhand clothing but caring for and donating items back to charity shops when she no longer wants them. She sees doing so as continuing an ethical and sustainable cycle, allowing the clothes to have new experiences. “I’ve had my time with it, or maybe I just didn’t make enough use of it, and it’s time to let someone else have their time with it now,” she says.

Newsletter

Newsletter